I’ve been reading my way through the Old Testament again and have reached the sad, sad beginning of the Great Brokenness.

I’ve been reading my way through the Old Testament again and have reached the sad, sad beginning of the Great Brokenness.

The tales of David—hero and king, poet and warrior, man of passion and lover of God—are really the sort of stories that blockbusters are made out of. Long chapters of his life, rich both in detail and in innuendo, create a moving panorama of light and shadows, grand events and bitter moments. And then there’s Solomon—all big and glorious, wise and rich and monumental and, well, gaudy and decadent too. And then it all comes to a crashing collapse as Solomon’s son is foolhardy and stubborn, and half the kingdom clearly was not so very happy under Solomon and thus seemed quite ready to secede from the union. Humpty Dumpty fell off the wall, and all the king’s horses (and he apparently had 12,000; 2 Chr. 9.25) couldn’t put it back together again.

Worse yet, King Jeroboam of the northern tribes—recognizing that this whole separate kingdom thing was going to be difficult if everyone kept going to worship the Lord in Jerusalem, capital of the southern kingdom—decided he’d offer an alternative worship experience, replete with golden calves and goat-demons and lots of convenient drive-by worship sites on high places, and a new, improved, open order of priests that didn’t need Levitical heritage. And so we see the beautiful icon of God’s kingdom broken, permanently shattered into warring, quarrelsome, heinous mockeries of what David had established.

And I found Pascal in 2 Chronicles?

Yes, oh yes, I did.

There I found a few terse verses that suffice to describe what must have been a radical upheaval in the lives of all Israelites everywhere—something on a smaller scale akin to the 1923 Greek-Turkey population exchange, or the grievous Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947 when more than 14 million people sought refuge in the country of their religious choice, or the 1974 Cyprus partition. Someone draws a line on a map and the rules of life are completely different from one side to the next. Everyone must reorder their worlds.

In c. 900 B.C., when Jeroboam of the North abandons the political unity centered around the spiritual worship of the Lord in Jerusalem, he must accommodate the religious hunger of his people without acquiescing to their spiritual needs to go to the Temple. Thus the goat-demons, shrines, false priests, etc. Many found this an expedient solution to the political separation. We can hear echoes of their thoughts: “Well, all that business of traveling up to Jerusalem was a hassle anyway. This way I can hit the shrine on the way home from the market. Done.” Others… well, those others had Pascalian hearts.

The priests and the Levites who were in all Israel presented themselves to him from all their territories. The Levites had left their common lands and their holdings and had come to Judah and Jerusalem, because Jeroboam and his sons had prevented them from serving as priests of the Lord, and had appointed his own priests for the high places and for the goat-demons, and for the calves that he had made. Those who had set their hearts to seek the Lord God of Israel came after them from all the tribes of Israel to Jerusalem to sacrifice to the Lord, the god of their ancestors (2 Chronicles 11.13-16).

Here we see the great restructuring. Levitical families, whose inheritance was tied to certain cities within tribal territories, abandoned their properties and wealth to relocate, preferring the proximity of the Temple to their own homes. This, perhaps, in a calloused moment, we can attribute to career jockeying. After all, they were laid off. But what about the next line? “Those who had set their hearts to seek the Lord God of Israel came after them…”

These are the ones whose lives had been plunged into uncertainty, whose religious knowledge until then had been a matter of pro forma, long tradition, routine, custom. They were “raised as churchgoers,” so to speak. Then they went to college… er, so to speak. And there they found riotous goat-demons, hmm, so to speak, and shrines, more literal, and a wild and wooly variety of worship experiences, exactly. And then, they had to look within and weigh their true desires.

Religious veneer? Convenience? Reputable appearance? = stay put and shift your allegiances.

Truth? Divine calling? Authentic spiritual reality? = pull up stakes and shift your heart into “seek-gear.”

The language is beautiful. They had “set their hearts to seek the Lord God of Israel.” Let’s not assume that they were necessarily responding to a consuming passion, as though it were written “they couldn’t stop themselves from hot pursuit…” No, you see here something even deeper than the desire—that is, the desire to desire.

Many of the great spiritual writers, particularly in the Western tradition, have written about the role of holy desire in the spiritual life. Pascal, however, reaches deeper and puts his finger on that painful place in our hearts when we really don’t desire, but somehow yearn for it anyway. Incline our hearts. (f. 821) Beneath the desire for God is the prayer for the desire for God.

We don’t pray “incline my heart” because it is already so inclined; we pray it when we recognize that our hearts are dusty and dull, and our desire for God faint and fallow, and our blindness nearly complete. It is a prayer that sets our hearts to seek, that orients our deepest selves toward what we can only hope is the true altar of God, that shuns all the goat-demons that bellow in the darkness.

All right, I had meant to write about the essential ways to nurture inclination, or “tend the fire,” but I had to stop for a moment and tell you that I found Pascal in 2 Chronicles. Thought you’d want to know.

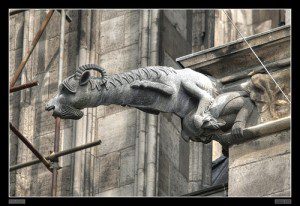

Photo courtesy Georg Schwalbach, Flickr C.C.

___________________

Note to Reader: This series on Becoming Neo-Pascalian considers some of the ways Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) speaks into the 21st century. It draws from my own research, published in Beyond the Contingent (2011), and citations are from the book, unless otherwise noted. The beginning of the series is here: Introduction.