Of course I don’t cuss. Well, not much. So that takes care of the Sermon’s verses about oaths, right? (You potty-mouthed people might want to spend more time with them though.) Ludolph, my medieval guide to the life of Jesus (see below), writes eight chapters on the Sermon on the Mount, concluding this one (Part One, Volume 1, Chapter 34) with several pages on Jesus’ words about oaths. Seems like overkill. We want to rush on to the guy who steals our tunic.

In my Bible, the Sermon on the Mount is broken into subsections with (uninspired) headings: Murder, Adultery, Divorce, Oaths, An Eye for an Eye, Love for Enemies. These are, of course, not discrete topics. From his discussion of true righteousness early in Matthew 5, Jesus proceeds to talk about rage, disgust, scorn, and relational brokenness; then lust and adultery; then divorce; then swearing and making vows; then revenge; then faithful love for enemies. It all could be seen as one overarching chapter on marriage and family. Certainly Hollywood has taken the cue—it all sounds like various episodes in a soap opera.

Ludolph seems to perceive the thread of Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 5 as a cohesive package around relationships. Chapter 6 will introduce acts of righteousness and spiritual practices, but chapter 5 definitely seems rooted in the inescapable conflicts that arise in the contexts of close relations. Once again, Ludolph pushes us beyond the letter of the law, beyond the words on the page, to what he believes is the heart that Jesus wants for us. According to Ludolph, the integrity of what is inside and what is outside, what our intentions are and what we project to others, is critical—critical to living with each other in righteousness.

This isn’t about rejecting proper or legal oaths, like an oath taken in court, or an oath taken before a minister in a wedding. (Oh. Ahem. Yes, there we are again, being pulled back into the issue of divorce, and adultery, and rage.) Rather, Ludolph says, it’s about being thoroughly reliable in what we say and do. He cites Chrysostom:

Swearing of any kind is not permitted to us. Why is it necessary to swear, since we are not permitted to lie for any reason? Should not all our words always be so true that they can be trusted as absolutely as if we had sworn an oath?

Is our Yes a real yes? Is our No a real no? Or do we play games with our talk? Do we deflect, dodge, and obfuscate so that we make people think something that isn’t true … even if we don’t actually lie about it? How about the tone of our voice? What does it communicate? Here’s part of Ludolph’s reflection:

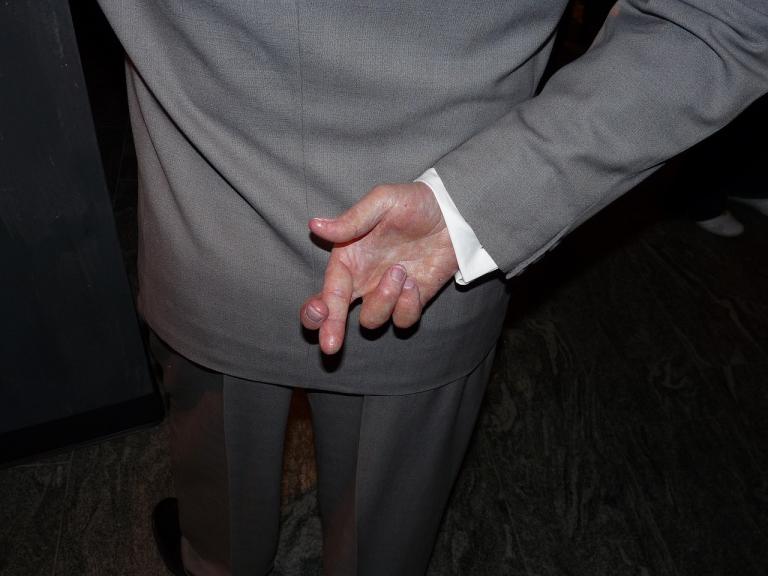

Jesus’ repetition of yes and no suggests that our mouth expresses externally what is in our heart. … Therefore, let what is in our conscience be on our lips, let what is real be in our mouth, and let what is in our mouth also be in our works. … And when talking, let us speak plainly and not send other messages by gesture or expression. (I’m not even going to begin to address the “messages sent by gesture or expression.” I think you all can fill in the blank there.)

So let me just push these reflections a wee bit. What does all this talk of speech have to do with murder, adultery, divorce, revenge, and faithful love?

We all know most certainly that sticks and stones do break bones, but words are way more powerful. They can bind and heal and create; they can destroy and corrupt and embitter; they can both set the trajectory of a life and ruin it. Things said cannot be unsaid. Lies break trust in ways that are very hard to mend. Thoughtless words generate rage and scorn (vv 21-22); they break relationships (v23). Careless words spoken to the wrong people can open doors of lust and seduction, and walking through such doors, according to Jesus, can lead your whole body into hell. They can set patterns of vengeance and spite that never end. They can fly out of our mouths like bats out of hell or they can simply be good and necessary and true words that are never spoken.

But they can also heal; they can restore and repair; they can bless and soothe. They’re not magic. The best words in the world can’t fix everything. They can’t make my grey hair turn black again. But Jesus’ words about our speech are powerful tools for dismantling rage, for repairing relationships, for rejecting infidelity, for remaining faithful.

Note: For a brief introduction to Ludolph of Saxony, a medieval “best-selling author,” read this.