And the Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.

In in these words, St. John encapsulates the wonder that is the Incarnation: the union of the Divine with His creation. As our liturgy draws us closer to the celebration of this wondrous event, it’s not surprising that the Incarnation and Incarnational theology take center stage during the Advent season. It’s hard not to ask ourselves: what does it really mean to say God became Man?

The problem with asking that question is that, as the holiest, most intelligent, and most contemplative of the saints know far too well, after we have said all we might possibly say on the subject, the Incarnation has far too much of reality about it for us to even begin to comprehend what God did when the Logos united a human nature to His Divine Person.

So what is faith supposed to be in this realm where words themselves fall silent in the overwhelming presence of the Word Himself?

It seems wrong to fall back on emotion—the stirring up within ourselves in the face of this piercing truth—because this truth is more solid than our ability to grasp it can ever be. It seems an even greater travesty to turn to sentimentality—if only because sentimentality is perhaps best characterized as a “degraded feeling—emotional schmaltz and artistic schlock,” to borrow the philosopher Eva Brann’s description.

So how ought a Catholic to respond to the truth of the Incarnation?

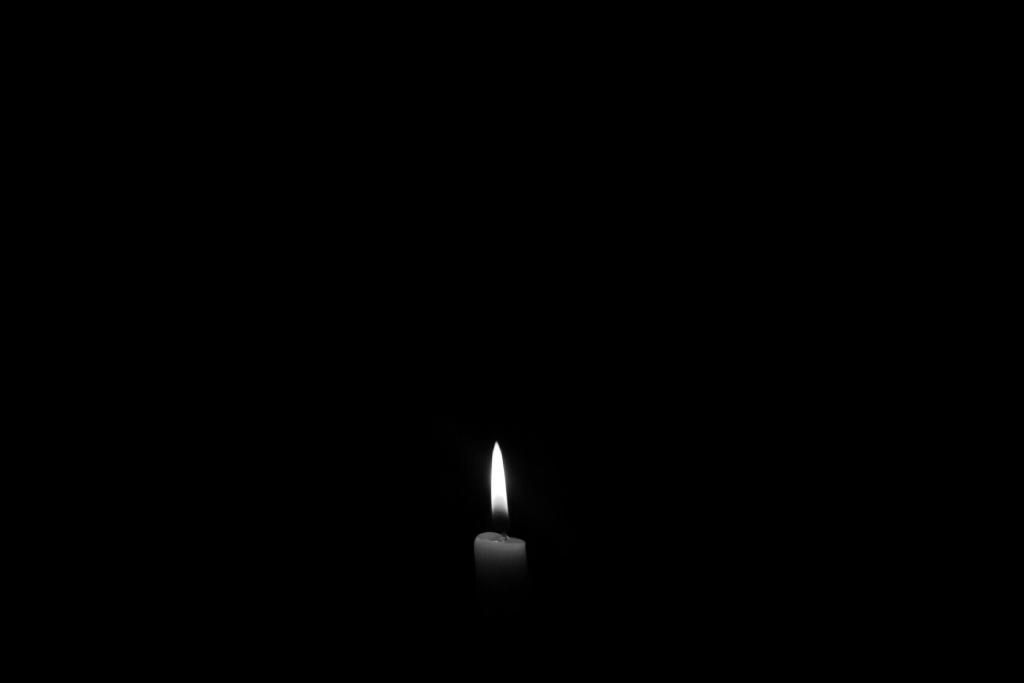

The symbolism of the Advent season offers us insight here: a single lit candle illuminating the darkness. The reality itself of the Incarnation, God became Man, is both the beginning and the end of our contemplation—the truth that resounds where our minds fall dark.

And yet, even in the darkness of our failed comprehension, some bit of the reality seems to spark into our minds. For,

There is in God, some say,

A deep but dazzling darkness, as men here

Say it is late and dusky, because they

See not all clear.

In Advent we are invited to contemplate what is incomprehensible: the union of a Divine and Human nature in the Person of the Word made Flesh. Our contemplation necessarily reaches what the theologians of old called the “vía negativa,” where we can only stammer that the reality of God is so much more real than what is dreamed up in our philosophies that our tongues fall silent in the face of it.

And, in that silent stillness, we perhaps begin to taste a hint of the wondrous love that would lead God to break bread with His creation.