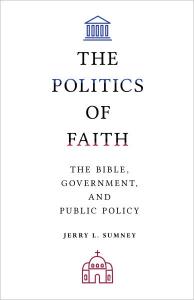

The Politics of Faith: The Bible, Government, and Public Policy, Jerry L. Sumney. Fortress Press. 200 pages. $16.99. Order at: https://www.fortresspress.com/store/product/9781506466996/The-Politics-of-Faith

Full disclosure: Dr. Jerry Sumney is my colleague at Lexington Theological Seminary (LTS) where he is Professor of Biblical Studies, and I am Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship.

“The Church should stay out of politics, and politics should stay out of the Church!”

In my experience as a preacher who has tackled social issues in the pulpit and encourages other clergy to do likewise, this is the kind of bromide I sometimes hear from those who wish that the church and the pastor would just keep quiet. Maybe it’s because the sermon interrupts their comfortable reverie on a Sunday morning. Or because they feel their ideology is being judged. Or they prefer to only hear about the “spiritual” aspects of the Bible. Whatever the reason, if they detect the preacher delving into public issues, they will not hesitate to voice their displeasure, anger, or threats.

Yet, the Bible is a political document, in the sense that it addressed the issues of public concern for its time.

Scripture talks about everything from taxes to immigrants to capital punishment, to name just a few “hot topics.” This means that if we take the Bible seriously and believe it should mean something for our lives and our society today, we need to discern its principles and values that can be applied to contemporary issues.

If you are a pastor or a lay person who is looking for solid reasons why the church should address policy issues, Jerry Sumney’s book, The Politics of Faith: The Bible, Government, and Public Policy, is just what you need.

In this highly readable book, Sumney uses robust biblical theology and exegesis to help readers understand the character and actions of God, the kind of public engagement God calls for in Scripture, and why Christians need to put their faith into action in the public square.

The reality is that Christians already use the Bible to help them think about their positions on social issues, whether they admit it or not. And, in fact, those who say that the church should stay out of politics when it comes to, say, protecting God’s Creation from pollution, are often the same ones who are fine with their church pushing to stop gay marriage or asking their pastor to write a Covid vaccine exemption letter for them “for religious reasons.” What Sumney does in The Politics of Faith is provide sound principles based on critical engagement with the Bible to guide readers to think about how faith can inform and shape the way we regard the relationship between the church and public policy.

In other words, it’s not a matter of whether the church and Christians should be involved in shaping laws and policy, but why and to what purpose.

Sumney’s position clearly aligns with the progressive Christian viewpoint that the church should advocate for equitable social and economic policies. This position grows out of more than three decades of biblical scholarship. In Sumney’s view, scripture demonstrates that God cares about the poor, the vulnerable, the outcast, and the marginalized. Consequently, God calls people to not only practice personal morality, but to enact laws that provide for the common good. Sumney supports this view by repeatedly showing how both the Old and New Testament are suffused with an ethic that, if enacted, would result in a more equitable and caring society.

Appropriate for clergy and laity

Sumney is a Pauline scholar who has authored seven books and has led several scholarly groups within the Society for Biblical Literature. However, this volume is written in a conversational tone free of academic jargon which makes it accessible for both laity and clergy. His skills in making biblical scholarship user-friendly for a lay audience have been developed over decades of teaching Sunday School in his home church, Lay School classes at LTS, and Bible studies in churches across the country.

Chapters 2 and 3 provide an overview of the Mosaic Covenant and the Prophets. One might wish that a few more chapters could have been devoted to the political ethic in other Hebrew scriptures such as the Psalms or the Book of Esther, for example. Nevertheless, these essays help the reader to see how the Torah and the prophetic writings served as “a blueprint for how to construct the kind of society God wants” (15). The Israelites are charged with creating a society where immigrants are protected, widows and orphans are not left to fend for themselves, and economic predators are kept in check.

Especially noteworthy is that Sumney includes a section on the Levitical laws, often ignored, overlooked, or dismissed by most Christians. From a 30,000-foot view, we see that the Holiness Codes are not about micro-managing religious minutia. Rather, they are intended to give very practical and detailed ways for the Israelites to live their lives in community. This is not just because God is pleased by this kind of holy living, but because “God is these things” – justice, mercy, holiness, and compassion (19).

Who, then, is the intended audience of these biblical writings? Is it just the common people within the faith community? Or are they targeted toward those with more power, influence, and authority?

Sumney’s chapter on the prophets gives us an important insight regarding these questions. Prophets like Nathan, Elisha, Micah, and Obadiah were addressing the leaders. “Clearly, these prophets are not speaking primarily to the average person on the street. Their messages are spoken most directly to those in power, to the people who run the government,” (27). Once we have established that this practice of speaking truth to power has its roots in ancient Israel, it weakens the argument that the church has no role in politics. In fact, the only logical conclusion is that clergy and congregations should speak up when having an opportunity to shape social, economic, and judicial law so that it comes closer to reflecting God’s justice and mercy.

The next seven chapters in The Politics of Faith survey the Acts of the Apostles, the Gospels, Paul and his letters, and Revelation. What each of these chapters stress is the way in which the teachings of Christ and the expectations of the early church differed dramatically from the values of the Greek and Roman worlds. Sumney is not shy about Christians and the church living and acting in such a way that reflects “what God wants for the world” (41). In Acts, for example, this means redistributing wealth and rejecting economic systems that perpetuate exploitation and poverty. As well, the Gospels show Jesus modelling public interaction on social issues. For instance, his exorcising of demons illustrates the power of God (and, by extension, the church) to release people from evil “imposed by the outside” (45) through systems and structures that keep people in bondage.

Sumney is also adept at unraveling troublesome and troubling passages in the New Testament to unearth the underlying dynamics of justice.

The disturbing story of the death of Ananias and Sapphira in Acts 5, for instance, is really about rejecting “the accumulation of wealth that comes through the exploitation of others” (39). Jesus’ puzzling parable in Matt. 13:24-30 about “the weeds and the wheat” is actually helpful when we encounter those intent on subverting the forces of good. This parable tells us that “we should not be surprised to find that some people around us oppose God’s will. It should also not discourage us” (55).

Even the passion narratives are political. “Crucifixion was a political execution. . . In all four Gospels, Jesus is executed on a political charge” (70). This is because Jesus was a threat to the rulers of his day. The fact that he was resurrected is not just a story of God’s power over death (which, of course, it is). It is also a theological repudiation of the entire economic, military, and religious system that demanded his death in the first place.

As you and your congregation read The Politics of Faith, you may encounter voices who insist that the Bible teaches the faithful to passively accept whatever the government decides to do. Some insist that the church’s only job is to follow Jesus’ command to feed the hungry, care for the sick, clothe the naked, and visit those in prison (Matt. 25:31-46) – not question the policies that result in hunger, sickness, or unjust imprisonment in the first place. But Sumney refutes that limited view. “Since governments are the organized ways that people structure how they treat one another, the people in charge are expected to create systems that exhibit the values God demands of each person” (61).

But doesn’t Romans 13:1-7 argue that God is the one who establishes governments? And, as such, governments should be allowed to conduct their business without interference from the church?

Again, Sumney adroitly dissects this misinformed position. “Acknowledging that governments are set in place by God does not mean God’s people should not oppose their unjust policies” (89). Romans is clear that the government’s role is not only to punish evil but to be “servants of God for your good” (v. 4). So, it is perfectly appropriate for Christians, in the prophetic tradition, to “hold governments accountable to God for how they wield the power God has given them” (91).

The final chapter of The Politics of Faith is “Being a Faithful Church in Today’s World.” It summarizes what the reader will have learned so far and offers “a biblical framework for determining what participation might look like for us and our church communities” (115). Sumney points to predatory payday lending, oppressive immigration laws, unfair economic policies, and the questions around “big government” as areas in which Christians can help to shape just policies and laws. “The message of the prophets is clear: Governments and rulers are expected to enact laws and establish institutions that protect people who have fewer resources and less power,” Sumney asserts (119).

This last chapter also provides a corrective to those who claim that the church should not address public policy because of the “separation of church and state.” Sumney clarifies, “Separation of church and state does not mean that the church ignores the injustices that our laws allow or prescribe” (120). This is not to say that the our system of government should be converted to a theocracy or that churches should endorse certain candidates. Rather, “we should want churches to speak out when candidates support policies that move further from God’s will rather than toward it. We should clearly state that our cultural individualism has led us to give advantages to those who need it the least” (121).

Helpful discussion questions

Each of the eleven chapters contains several discussion questions which are sure to spark generative conversations for adult forums, clergy groups, and personal reflection. A pastor might consider inviting their governing board to read a chapter a month over the course of a year and pick one or two discussion questions that can guide decisions about the church’s ministry. A youth pastor working with senior high school students could lead a Bible study and draw on Sumney’s book for reflection and discussion. Denominational leaders could invite clergy to read and discuss The Politics of Faith in colleague groups within their judicatories or in ecumenical gatherings.

However this book is used, The Politics of Faith is a welcome corrective to misunderstandings about the Bible, what it meant to its original audience, and how it should be applied today. Sumney’s book is a helpful tool for informed civil discourse about the role of the church in an unjust world. And it can guide discernment and discussions about how congregations can live out their mission to reflect God’s justice, love, mercy, and compassion in our communities and society.

Want to hear more from Jerry Sumney about the Bible and public policy? Register for The Bible, Politics, and Ministry: Guidance for Clergy and Congregations, a conversation with Jerry Sumney and Efrain Agosto, biblical scholars who will explain how Scripture authorizes and compels us to engage public policy as part of our faith. Hosted by The Clergy Emergency League and the Wisconsin Council of Churches. Tuesday, September 21, 2021, 7:00 Eastern, 6:00 Central, 5:00 Mountain, 4:00 Pacific. To register, click here.

Read also:

Latinxs, the Bible, and Immigration

Abortion and the Progressive Church: Is It Time to Break the Silence?

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). Her latest book, co-written with Jerry Sumney is Apocalypse When?: A Guide to Interpreting and Preaching Apocalyptic Texts (Wipf & Stock, 2020).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/