I have experienced, as I have said, some guilt about creating this writing chamber, and that is usually owed to the good intentions of the people around me whom I love and who love me but cannot really write to save their lives. Feeling guilty about writing – and reading, for that matter, as this is the mental food that sustains a writer – is probably the surest way in my experience to bring about the collapse of the writing chamber. There are many ways that this implosion can happen, and I have discussed in my previous post the path of depression, of the complete paralysis that comes about in which an author simply stares into space unable to move. As I said, I have been there, recently even, so my thoughts on sustaining a writing chamber are probably fresher than I would like to admit that they are. In fact, the thought has even occurred to me that I am jotting them down in order to make sure I do not forget them in my hour of need.

Today, I want to talk about chastity. Because the writing chamber is as much a mental space as it is a physical one, the contours of that intellectual place might be messier than what I might want to even confess to my spiritual father in the Holy Mystery of Repentance. The way that I have been taught in the secular academy, for example, emphasizes that writing is a kind of task, a labor, something that you just have to do with your hands, and I think there is wisdom in that, in the sense that in its barest material sense, writing is something that happens when hands meet plastic and engage paper or screen. The thing that they do not teach you in school, though, is that when you do that kind of thing, your intellect becomes focused outward, squeezed by those hands to conjure up figures that are visible. The trouble comes when that conscious part of the mind is not exactly clean, and it is for that reason that I want to discuss the importance of chastity for those of us whose lives are spent at work in the writing chamber.

The best description of sex that I have ever read is in the opening pages of the political psychoanalyst Alenka Zupančič’s newest book, What Is Sex? The working definition that she uses posits that sex lies at the gap between ontology and epistemology, between what is and how it is known. I think this is a great précis concerning the task of writing too. In some ways, all of writing is aspirational, in the sense that a writer aspires to create a piece in which the world they are describing is contained in the words that they are setting to paper, and on some days, this is more of a struggle than on others. Part of that wrestling, though, has to do with the chasm between what I am really trying to do in my writing versus the fantasies that are conjured up as I try to write down what I am trying to describe. Giving in to those fantasies is often the easy thing to do. Powering up against them is the uphill battle.

When I say fantasy, I suppose those with dirty minds will think that these phantom hauntings are purely pornographic. They can be, and often are, but need not always be. I prefer the word transference instead because it can be a catch-all for all of the intimate situations that are brought into the writing and which must be dealt with in order for the writing to continue effectively. Perhaps it is the condition of my writing being so personally oriented that I am always susceptible to such temptations. After all, I not only write about postsecular Pacific publics, but also engage in them too as a person, with all my being that is liturgically formed in my participation in an Eastern Catholic church. In this sense, a number of phenomena from the unconscious can arise even if there are no external distractions, like social media or family members or students or colleagues or random noises. In fact, what is usually distracting comes from within, not from without. I once admitted to my spiritual father that I had a long stretch of unproductivity, and I attributed it to spending too long on Facebook. His response was very insightful. He noted that the bigger problem was that I was in a spiritual state of desolation, of feeling the absence of God’s grace more than his presence, and that it requires the motivation of passions like envy to be able to scroll through one’s newsfeed absentmindedly. It’s not just sloth. Something deeper is going on, usually.

When Freud talks about transference, what he technically means is that the faculty of free association in the consciousness latches itself onto an intimate situation of the past, especially in one’s childhood, and projects it onto an analytic situation in the clinic. Transference is the basis, in turn, for Freud’s musings on childhood sexuality because the conception of transference relies on having those latent memories to transfer in the first place. In many ways, this is what fantasy is too. It’s turning the situations of the present into a mirror of the things in the unconscious that are buried in the past. All of these fantasies are technically sexual in the sense that they engage a kind of primal intimacy, but they are not necessarily all dirty. They are memories of intimate relationships, of a mother’s relationship to a child, of a father’s relationship to a child, of a childhood crush, of sibling rivalries, of things one might have seen or heard on radio or television. The act of writing as an aspirational act conjures up all of these phenomena and has the ability to distort the writing chamber. The practice of chastity involves knowing how to channel these fantasies effectively so that the mental room doesn’t collapse on itself.

The worst thing to do when encountering a fantasy while in the writing chamber is to repress it. It is an easy mistake to make because of the desperation that an internal threat to one’s livelihood as a writer can make. The vice there then is not the repression; it is the desperation itself. Quick fixes like repression in the moment spell long-term disaster. The better idea is to channel it. The question is what those channels might be.

One solution that is often suggested is physical, and by that, I do not mean resorting to either alcohol or self-pleasure – or as younger Latin priests tell me they have been trained to say in the confessional, self-abuse, a term that is exquisitely pregnant with meaning in the present life of their church. There are three basic necessities that are usually discussed when it comes to chastity, and they are nourishment, exercise, and sleep. One of the most productive scholars I know, for example, moonlights as a body-builder; he hits the gym daily at about eleven o’clock and plays soccer on the weekends. Others might emphasize their diets in terms of how much food and drink they can take in, how much coffee is their limit (an important question indeed), and how water is perhaps the drink of choice when engaged in a serious project. Finally, the Eastern Catholic liturgist Robert Taft SJ once said that the most important thing in becoming a great scholar is to go to sleep and wake up at the same time every day. There is wisdom, I reflect, in these words. I also find the physical acts of showering, shaving, and trimming my nails to be uniquely expiating.

Another venue that I have discovered is a liturgical one. Basically, I see my weekly practice of the Byzantine liturgies I attend as a kind of studio training in a martial art. What happens in the liturgy is correlated to everyday life, so if there is a passion I am working to untangle, I might use my prayer in the liturgy to work on untying it. This was particularly useful, I found, over the summer when I was cantoring because it militated against my propensity to second-guess myself. The actions of the liturgy are a little bit like how my body-building friends talk about using weights to reset their posture. The liturgy also resets the postures of my heart. To let that practice become more regular, I also find that the Byzantine daily prayers, such as the Jordanville Prayer Book’s Morning Prayers and Prayers Before Sleep, help me to channel those studio exercises into ones for home.

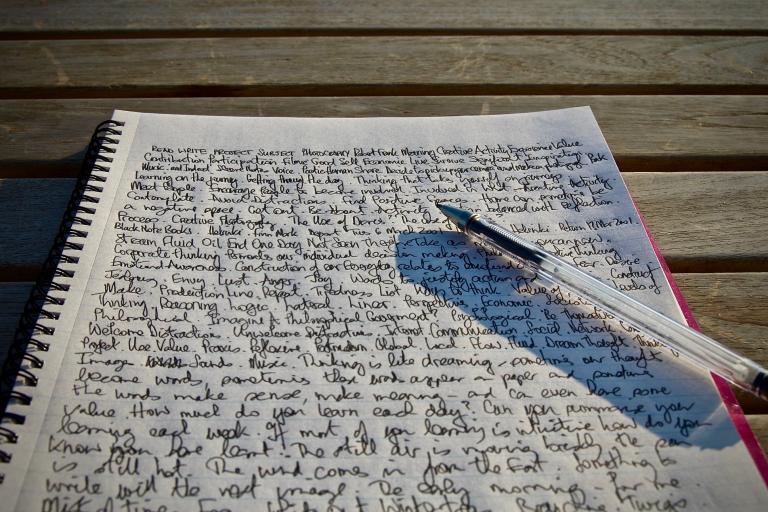

But the most important thing to do with a fantasy, I find, is to channel it. There are a few main ways I do it now, and all of them seem to be bearing fruit. The first is regular confession and spiritual direction with my spiritual father, and I particularly like his style because he doesn’t want to hear all the details, just the highlights, and help me work through the practices of discernment through some selected examples so that I can take the rest home as homework. That homework is done in the second site: a handwritten journal, where I find that writing out the fantasies has a unique way of robbing them of their power. While those writings are absolutely confidential, some of their insights become curated for the blog, which is why I incorrectly thought of this site initially as a place for ‘hysteric confession.’ It is not. They are insights that I have already worked through, now brought to a broader audience partly as a way of getting it out of my system and partly because I honestly think that there is mutual benefit between myself and my readers in having them read. I also have personal conversations with a number of people, some of whom are on instant messaging, but increasingly, I am moving those dialogues to email.

Each of these methods is a kind of interior organization that I am finding increasingly necessary to sustain a writing chamber. Chastity in this way is about economia; in the case of a writer, that means that one’s mental palace has to cleaned, arranged, and have the trash taken out every so often. It has taken some intellectual deep-cleansing since my conversion, especially during the period described to neophytes as their mystagogy, for me to be able to write these out as my regular practices, although the truth is that I am still working on fine-tuning all of these methods. But I think what I can say now is that there are real effects to mystagogical work, as I am finally starting to feel a little different.