As I was going about my day on this fine Sunday Before the Exaltation of the Cross and Postfeast season of the Nativity of the Theotokos, my friend, colleague, and brother Eastern Catholic scholar Adam DeVille posted on my social media. It turns out that September 23 is the anniversary of the death of the great male theorist of the death-drive, the one we have dubbed St Sigmund of Vienna, known by the secular world simply by the name Freud. Of course, he is not the inventor of the death-drive. That falls to a psychoanalyst who is much greater than the man (and the rest of the men in the field, for that matter), Sabina Spielrein.

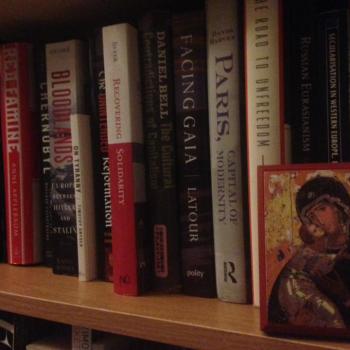

It is in fact my view that the women in psychoanalysis were probably better than their rigid male counterparts. In my home bathroom, I have put up a shrine to them. The places of prominence, if one observes carefully, fall to Spielrein, Melanie Klein, and Anna Freud. On top, their descendants from Ljubljana may include Slavoj Žižek, but the true great one of their trio is, in my view, Alenka Zupančič, twice the author of books that Žižek confesses to have wanted to write, Ethics of the Real and What Is Sex? Of course, Žižek didn’t write them. He was not capable of the work that Zupančič executed.

Freud was much the same. As a friend of mine who is a Greek-Catholic priest and a practicing psychoanalyst never ceases to remind me, Freud had much the same flaws as those of whom he accused others. If he is the godfather of patients with daddy and mommy issues, he himself had them the worst. With his male colleagues, everything had to be done in his own rigid way. When Alfred Adler and Carl Jung broke ranks with him even in the slightest matters, he unfriended them so publicly that the history of psychoanalysis would have been markedly different if he had been friendlier. The obverse goes for the women. Spielrein literally handed the death drive to him on a silver platter — one could even accuse the old man of plagiarism at some points — and his daughter Anna explicated ego and child sexuality in ways that he could not imagine.

What, then, is this cranky old man good for? If his most central ideas were developed by those around him, then who cares about him? Why even give him the facetious honorific St Sigmund of Vienna? These questions are all fair, and I will wager that if Freud had not literally been such a dick, psychoanalysis would be a much more respectable discipline. The shrine to the field would not be in my bathroom; it might even be in my closet, though the truth is that that space is currently occupied by my explorations of cinematic transference.

A perverse reading of Edith Wyschogrod’s classic Saints and Postmodernism might reveal an answer. Wyschogrod argues that in the current time in what the theorist Jean-François Lyotard calls highly advanced societies like ours, that the question of truth and its criteria in the public sphere is up for grabs demands that actual lives lived in real human bodies show of what the moral is actually made. Morality in this sense is not a set of rules to be followed. It describes a sense of relationality that is in actual accordance with the way that the world is, in ways that are actually integrated with that sense of reality. The truly moral is grounded. It is not abstract. It is the provenance of the body.

If Freud was as much subjected to mommy and daddy issues as the patients that he analyzed, then his bodily life demonstrates the truth of the transference phenomenon, the propensity for persons to transfer intimate situations in their past onto present encounters as if they were mirrors. In Dynamics of the Transference, Jung recounts the moment when he confesses to Freud that he thinks of transference as the ‘alpha and omega’ of the psychoanalytic project, and Freud famously responds: ‘Then you have grasped the main thing.’ It is important to break the mirror in an analytic situation – and I find that this is as true of scholarly work and ecclesial life as it is of the clinic – but there is a sense in which any time I think that I have fully broken out of the hall of mirrors and am finally free, that is the truest moment of danger. As Žižek points out as far back as The Sublime Object of Ideology, the moment when we think we are outside of ideology is the moment when we are the most fully in it. The most honest of those who give themselves to the seriousness of psychoanalysis as a mode of critical engagement with the world are able to confess that they will never be free of the transference, and that it is also not always bad, and that it is usually detected in hindsight and not in the moment.

On this Feast of St Sigmund of Vienna, we remember the old man’s flaws more than his contributions, then. We look back in hindsight and find that the one who showed us the way of analyzing transference was himself the most caught up in its processes. Rescuing us from our contrived puritanism, such reflections take us into the very bowels of our being. Freud’s throne in our hearts is the toilet, and the bathroom is his throneroom. Clean as we may try with as many flushes as we can afford, there is always more to digest when it comes to transference, and as Žižek reminds us in the work of the greatest of the psychoanalysts, Hegel, in his preface to The Sublime Object of Ideology, the truest reading of Hegelian synthesis is not progress, but the constant undoing of the constipation of the Idea, digesting it into the fecal matter that must be deposited into the watery space beneath the throne of our hearts.

For those of us in the apostolic churches, perhaps this disgusting image offers a fresh view of what happens in the space of confession, the Holy Mystery of Repentance. Some, including Pope Francis, have suggested that psychoanalysis is a secular form of confession, and they are not wrong. But if it is the case that – as others have demonstrated in the recent theological literature – that secularity is but a masking of theological phenomena still at work in the real world, then does not the clinical moment of the transference becoming analysis and not merely lived – when the analyst points out to the patient the mirrors that they bring to the encounter – mirror what happens in our confession before the holy icons, when we look at them and realize that they are not mirroring us but actually gazing through the windows of heaven upon the sins that we, not they, have committed? Is not the whisper of the spiritual father behind us overhearing our confession the voice of the other that disrupts the self-narration by which we have been tied into unconscious knots? And with this question I end: is not the exhortation to regular confession before Divine Liturgy not a statement of the supernatural truth that underlies the medical usage of regularity in the sense of how smoothly one’s bowels perform when enthroned upon the Iron Throne of each of our residences?

More information about the Kyivan Psychoanalysis Study Group can be found here.