My friend Abraham used to bake cranberry bread for communion at an evangelical church that my wife and I used to attend in the late stages of my doctoral work and well into my postdoctoral fellowship. There was a reason we went there. When we got married, Jenny was not Anglican, whereas I was. Not wanting to leave either of our communities, we shuffled between churches every week until we were tired of the inconsistency, at which point I was invited to speak at this church where Abraham was baking bread. We fell in love with it because they had a picnic lunch after service, and their families across multiple generations from toddlers to grandparents all had fun together. We still have many friends there. I even wonder if we might have stayed there long-term had I not continued to move up the liturgical ladder. In fact, I was at the time much in the vogue of using a particular spiritual gift that I had in building up the community: gathering folks for a cheap, hot lunch after church when picnics became untenable because of rain or cold weather.

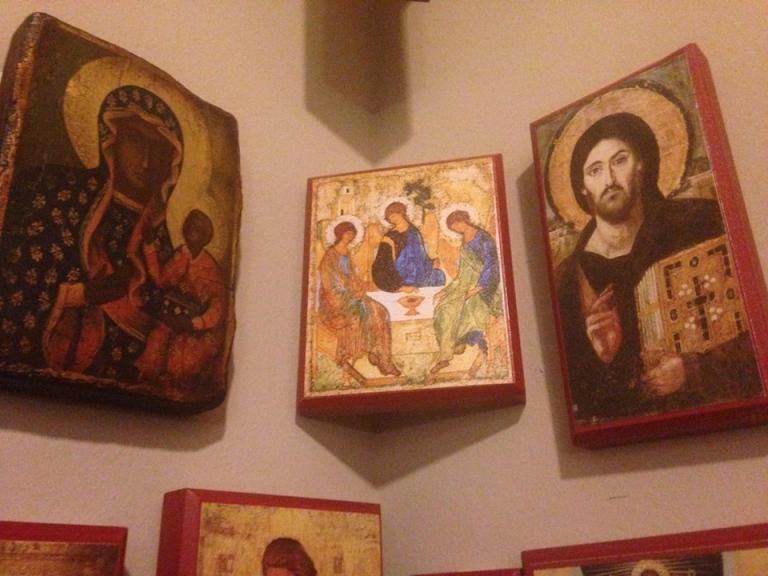

This community had a very interesting communion practice. Being an evangelical church, they did not have much by way of a consecration for the bread and wine, which is why Abraham’s cranberry bread was acceptable, although the intriguing part is that they used real, alcoholic wine instead of Welch’s grape juice. They did not mind my high Anglican understanding of the Real Presence, and it worked out because my wife was raised to think that my views were weird and that nothing changes, happens to, or transforms in the bread and the wine in communion. Nobody judged anybody else on the question of what communion actually was, but everybody took it, including folks I knew to be communion with Rome in a canonical sense. Come, they would announce, the table is ready. Come, join the feast, they would add, inviting the people to partake of what they would announce to each person as the body and blood of Christ. As we would partake of the large chunk of cranberry bread that would be given to us soaked in red wine, a guitarist would play worship music. On the projector screen, however, they did not project lyrics. Instead, it was the Russian iconographer Andrei Rublev’s classic icon, the Trinity, or as it is less commonly known, the Hospitality of Abraham.

Abraham has since followed me in attending the Eastern Catholic Church in Richmond, though his journey to full communion may take a while yet. We describe each other as brothers, which means that I have enjoyed his hospitality so many times that I have stories about it. One time, he plied us with so much scotch that we were so sure we were going to be arrested for driving under the influence at a traffic stop in Richmond. Fortunately, he had also filled us up with ‘turducken,’ a chicken wrapped in a duck and then stuffed into a turkey, that when I blew into the breathalyzer, it showed that I had zero blood alcohol content. To me, this story is Abraham in a nutshell, generous to a fault, to the point where we want to fault him. The other part that epitomizes this ‘good brother,’ as we call each other in Cantonese, is that he likes to follow me around, even from his background in Chinese Protestantism and Asian Canadian evangelicalism into the beautiful chaos of our beloved Kyivan Church.

As Abraham follows me around, he often likes to ask me for my advice about a number of things. Sometimes I feel bad that I cannot answer well because, unlike him, I am not a real estate agent, a jet-setting entrepreneur who has flown on more flights through Asia in the last year than I have fingers, a chef, a violinist, an orchestral conductor, and a person who can actually claim to be from Hong Kong. Still, he persists, often trying to understand my intellectual work or my spiritual journey or how he will eventually convince someone to be his girlfriend. Feeling that I usually lack answers for his needs, one time I asked him to remember the icon on the projector screen at that church that we used to go to before we both discovered Eastern Catholicism. Oh yes, he said, Rublev’s Trinity, and then he said something about Tarkovsky, and I thought to myself, of course he would say that, because Abraham’s modus operandi is to inform you in daily conversation that he really does know what he is talking about when it comes to cultural phenomena. We are brothers because we are completely different from one another, as I make it a point to emphasize my ignorance of such matters.

I was in the catechumenate at the time, so I was not as ignorant as I usually am. I was learning from Bishop Kallistos Ware’s Orthodox Church (which is much better than The Orthodox Way) that Rublev’s Trinity had been dedicated to the Holy Monastic Sergius of Radonezh. Ware’s assessment of Holy Sergius is rather uncontroversial: it is that Sergius managed to combine monastic discipline with administrative know-how and basically built the lands of his monastery so that it led to the expansion of the backwater town of Muscovy into the city we now know as Moscow. Later on in the book, Ware describes an intriguing split that happened in Russian spirituality between the Possessors (those who thought monks should own land) and the Non-Possessors (those who thought they shouldn’t) and attributes it to a division of Sergius’s integrated approach to the world. Abraham’s problem, I strongly felt at the time, was that he had trouble integrating his work and his everyday life, so I encouraged him to get the icon of Rublev’s Trinity. I’m pretty sure he did not follow my instructions.

I am glad Abraham usually takes my recommendations with a grain of salt and has been building an icon corner through the advice of spiritual masters far more competent than me. Looking back on my recommendation, I feel like my understanding of the icon when I recommended it was a bit juvenile. It was more like an art history critic, and an amateur one at that, rather than as a worshipping participant in the scene. What I came to understand much later is that the icon was like a meditation on the communion scene that sits above our iconostas in Richmond as well as the one that takes the place of where the Oranta should be in our temple in Chicago. In both cases, the icon is displayed with the table facing outward, inviting the viewer to participate in the scene. The evangelical community that Abraham and I attended had it mostly right. Come, the table is prepared. Come, join the feast.

It is like the time I visited the Orthodox Church in America cathedral here in Chicago, which is named for the Holy Trinity and displays Rublev’s icon prominently. An older Russian woman greeted me and asked me who I was and where I was from. I replied that I was Greek Catholic, and making a gesture to say it was no big deal, she told me it was all the same. She even drove me to the train station that night, during which she said loved to listen to Patriarch Kirill chant the tropars for the Great Canon of St Andrew of Crete and even put some on for me to hear. I would not say that Kirill, or the Moscow Patriarchate, or the Orthodox Church in America in its contemporary form, are what we might describe as friendly to us Greek Catholics. Indeed, in the invasion of Ukraine since 2014 and in these more recent dangerous times of the preparation of the Tomos of autocephaly, Russian aggression on the Sea of Azov, and the Ukrainian government declaring a limited form of martial law, the term uniate has returned to being fighting words beyond the ecclesia and well into the question of nation and peoplehood. Ukraine is accused of being run by uniates, a reductive sentiment used to justify the fantasy of a Russian World in which neo-imperialist powers in Moscow rule over the ‘holy trinity’ of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. And yet, despite these larger geopolitical realities, there I am, in the car of an older Russian woman who has recognized me, a Greek Catholic, before Rublev’s icon of the Trinity to be a brother in Orthodoxy, listening to a patriarch who hardly hides his neo-imperialist ambitions chant verses of repentance.

Rublev’s Trinity now is centered at the top of my beautiful corner, and I keep a copy in my academic office as well. I realize now that it is not an icon that Abraham needs, but one that I require as I process my brotherhood with Abraham and the unexpected graces he frequently introduces into my life. Communion in this icon takes me to its background: a house, a tree, and a mountain. Through communion with the Trinity, we are ushered into the economia of the house of God. By eating with the three persons of the Godhead pictured at table and drinking from the cup on the table, we partake of the tree of life. In so doing, we ascend the mountain so that in our prayer, we might shine with Uncreated Light. Politics, the practice of everyday life, and prayer are all one integrated whole in this icon because communion describes our approach to a common life on an earth created by the Trinity and infused with divine supernatural grace.

It makes sense, then, that my encounters with Rublev’s Trinity would be so messy. Abraham following me around with his hospitality, an icon projected onto a screen in an evangelical community that is agnostic about communion and intincts cranberry bread into wine, being recognized as Orthodox by a woman devoted to the Moscow Patriarchate: these encounters would not be possible without the backdrop of the Triune presence. In partaking of the feast spread at the table, I am initiated time and again into the mystagogy of everyday life lived in a supernatural world, which means that my spiritual encounters gloriously trespass ecclesial and political boundaries all the time. But such universality is possible with me being rooted in the local church that I am in, where I partake of the Body and Blood among the people of God gathered in the Kyivan Church under the omophor of our bishops. That particularity is my entry point into the messy universal, where Father, Son, and Holy Spirit meet me with holy food and invite me into the world as it truly is, where the material order is always bubbling over with the spiritual reality that constitutes it.

These reflections on the icons in my beautiful corner compose the series I am writing for this year’s St Philip’s Fast in preparation for the Feast of the Nativity, beginning on the Old Calendar as I am in Chicago and switching back to the New Calendar when I return to Richmond in mid-December. They are attempts to account for my process of conversion in the Kyivan Church without discounting the Chinese Christianity of my Protestant past. This post is the second.

The previous post is on the San Damiano Cross.