There are basically two reactions that Chinese people have toward the West, which is any imaginative geography constituted by people who can pass for white. The first is complete, dripping, and uncritical admiration to the point of denigrating Chinese culture as completely backward, patriarchal, hierarchical, and despotic and therefore holding back Chinese progress into the modern world. The second is the China Can Say No attitude, which is that the West is a colonizing power that makes Chinese people feel inferior to it and for the sake of dignity, Chinese folks should cut themselves off from it and make their own culture. Usually, these two impulses are offered at the same time. The implication is not that Chinese people are culturally predisposed to indecisiveness. It is that the West is really confusing.

I am, however, generally opposed to both of these moves. When I was an Asian American evangelical, I felt stuck in trying to articulate why, partly because I engaged in a kind of alienation from my own sense of Chineseness at the time too. But on the Feast of St Nicholas in 2015, that bit about being alienated began to change. I had just become a catechumen in our Eastern Catholic Church the day before. Meeting with my spiritual father, he had asked me to send him an email confirming my desire, and when I did, he sent me a list of the Twelve Great Feasts, requiring my presence at each of them and recommending that I attend as many of the Vigil services and special feast days I could as well. The idea was to get a sense of the breadth of the life of the church I was joining. Now that I am in this church, I understand much better what he was trying to do. He wanted me to know what I was getting into before I got into it. Of course, I maintained my modus operandi of stumbling in the dark toward clarity. But these requirements paid off — it’s how I fell in love with the Kyivan Church.

The very next day after I sent that email, it was a Sunday. I went to liturgy. It was December 6, the Feast of St Nicholas on the New Calendar, and my spiritual father decided to tell a few stories about who the Holy Wonderworker Nicholas of Myra was and why we love him so much in the Eastern churches. He told the usual stories about who St Nicholas was, his generosity to his people, and him saving a family from having to sell their daughters in sex slavery in order to pay the bills. These were stories that I knew from the strangest of places: when I was a kid, the evangelical missionary ladies with their felt boards with cut-out pictures told stories of a guy called ‘Nicholas’ that the secular world had turned into ‘Santa Claus’ but really was a Christian who helped those in need. I got all that.

But then, my spiritual father made the point that of all places, early twentieth century China was a place where devotion to Holy Nicholas of Myra was a thing. This was partly because of Russian (and by extension, Ukrainian) settlements in Harbin and Shanghai, where local Orthodox communities (and by extension, Russian Catholic ones too, which as we all know are really our Kyivan Church’s mission to Russia strongly supported by Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky) grew and flourished. There was an icon of St Nicholas in a train station in Harbin, a city way up north in China, and though it could not be said that the local population was all Orthodox (far from it), there were a lot of candles put out in front of it. One day, as my spiritual father retold a story originally recounted by the Holy Hierarch Philaret of New York, a man was crossing a lake of ice and slipped through. He was not Orthodox and did not know St Nicholas by name, but in desperation as he was drowning, he cried out, Old Man from the train station, save me! And there he was, transported from the freezing water as if by teleportation to the train station before the icon of St Nicholas.

This story shook me to the core. Growing up Chinese evangelical, I had always been taught that what we Chinese need to do is to come up with the Chinese version of everything: a Chinese church, Chinese mission societies, Chinese faith-based organizations, and so on and so forth. But that this Chinese guy knew to call on the Old Man from the Train Station illustrates what Michel de Certeau SJ calls the practice of everyday life, that he may not have really known much about Orthodoxy, but it permeated his day-to-day space so much that he picked up on it, used it for his own purposes, and the brilliant thing is that St Nicholas heard his prayer and answered. There is no insecurity here about being Chinese, no double-thinking about whether it is appropriate for Chinese people to be devoted to the Old Man from the Train Station. In the same way, there is no sense in which the Chinese man had to become Russian, or Orthodox, or anything other than who he already was living in the place where he did to call on St Nicholas. Holy Nicholas the Wonderworker is first and foremost a person to whom persons can address and who answers them personally. There is universality in this Chineseness: Holy Philaret tells another story in which a Russian missionary saw an icon of St Nicholas hanging in the home of a Chinese family and thought because they didn’t know who he was that he was entitled to have it. Why are you taking away this old man who has done so many great things for us? the family protested. To them, St Nicholas was part of their family, precisely the kind of Chinese sensibility around the home in which who constitutes your relations are simply the people who are gathered at table under the same roof as you.

In this same way, there is no problem in saying that the Russian — actually Ukrainian, because he is from Donbas — hierarch, Holy John Maximovitch, is really of Shanghai and San Francisco. He was part of the local people, his status as bishop arising from among the people gathered at the liturgy, which included not only Russian emigres, but local people in both places. There is an article, in fact, going around my social media networks about how these emigres introduced borscht to the local food culture of Shanghai. The trouble is that there were no beets that they could use, so they substituted in tomatoes, oxtail, and red cabbage. When they were yet again exiled because of the Communist Revolution on the mainland, they ended up in Hong Kong, where this kind of tomato-style borscht became a staple in local Hong Kong food culture.

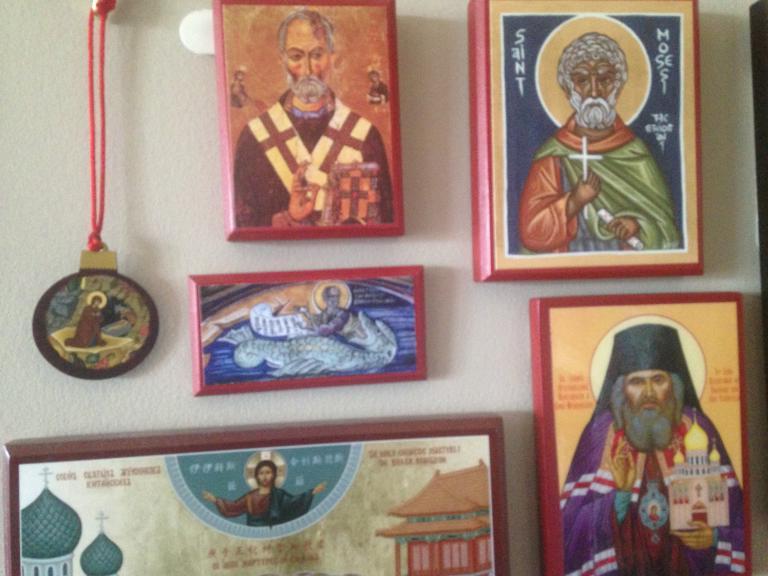

Hong Kong borscht is precisely how I feel about my devotion to the wonderworkers Holy Nicholas of Myra and Holy John of Shanghai and San Francisco. They are in my icon corner reminding me that my Chineseness is not an ideological or nationalistic claim, but a pathway into universality through the practice of everyday life, where the supernatural is to be found. I am also in the St Nicholas Eparchy of the Kyivan Church, and our sister Russian Catholic temple in San Francisco is around the corner from Holy Virgin Cathedral where the incorrupt body of St John of Shanghai lies. Being devoted to them doesn’t make me anything more or less than what I already am because they meet me personally and commune with me as persons. In this way, I am being led into salvation in ways that do not necessitate nationalist fantasy. Instead, it is a bit more like eating borscht together. Nourished by the same food, we look forward to our heavenly communion.

These reflections on the icons in my beautiful corner compose the series I am writing for this year’s St Philip’s Fast in preparation for the Feast of the Nativity, beginning on the Old Calendar as I am in Chicago and switching back to the New Calendar when I return to Richmond in mid-December. They are attempts to account for my process of conversion in the Kyivan Church without discounting the Chinese Christianity of my Protestant past. This post is the ninth.

The previous posts are on the San Damiano Cross, Rublev’s Trinity, the relation of the Black Madonna to the Oranta of Kyiv, the Sinai Pantocrator in relation to the Dormition, the ‘angels and archangels,’ the Prophet Jonah with Moses, Elijah, and John the Baptist, the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul, and the Holy Apostles Thomas and Jude.