I was having a think recently about whether the icons in my beautiful corner are reflective of my spirituality, and my tentative conclusion is that they do not. If they were reflections, then my prayer would be pure projection. If I could allow myself to be caught in the ideological fantasies of such a secular view of the supernatural, then perhaps I could be persuaded to see my icons are mirrors. But I prefer to be true to my own experience of them, and it is thus in honesty that I must theorize them as reaching out to me.

I, for example, do not intuitively like icons of Christ as the Pantocrator, the Ruler of All, especially portrayed as a judge. For one, I was raised to think of images of Jesus as borderline idolatrous, things that only Catholics had, especially that thing with white Jesus blessing the viewer and streams of color coming out of his chest (I later learned that the original image of the Divine Mercy was much less leung, as we say in Cantonese – kitsch to the point of evoking shivers). And then, I did not feel that such images of the Lord were very intimate, which is what we pursue in evangelicalism to the point of us being mocked for thinking that Jesus is our boyfriend.

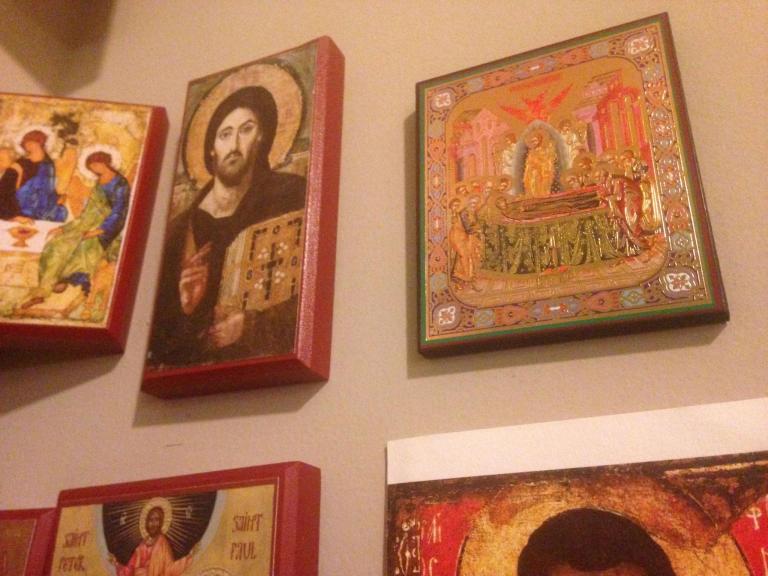

I learned early on in my icon acquisition that I should probably have them, and in the process of learning what was available, I discovered that there are two kinds of Pantocrator icons, Christ the Judge and Christ the Teacher. The difference lies in the book that he is holding in his hand. If the book is closed, he is coming to us as judge. If it is open with the letters alpha and omega or with his instruction to come to him to find rest because his yoke is easy and burden light, then he approaches us as a teacher. I am myself a teacher in a university, so I like the gentleness of Christ the Teacher, and I figured that if I had to get an icon of the Pantocrator, maybe I’d cushion my selling out by at least getting one to which I could relate. It is how he is portrayed facing me when I worship in Richmond; the icon on the right side of the iconostas is that of Christ blessing us as worshippers while holding an open alpha-and-omega book. So too, here at Northwestern, the Sheil Catholic Center has a Christ the Teacher Institute where members of the university community are invited to learn Catholic theology for a stronger practice of their own faith. Christ the Teacher is reflective of who I am in terms of my own sensibilities, and I even purchased a Russian icon of Christ the Teacher holding an open book to find him for rest that I hang in my office icon corner.

But in my home, the icon of Christ in my beautiful corner is that of Christ the Judge. It is, as I learned, the icon that is at St Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai, the Orthodox monastery that is open to all people of good will to come and pray. I just know it, though, as the face of the Lord whose eyes met mine when I was looking for an icon of the Pantocrator to set up my first version of the beautiful corner. Searching for icons of Christ the Teacher, I fell within his gaze, and it was the same sense that I felt when I first began to get a sense of what it mean to worship before the icon of Christ as a catechuemen in Richmond. As I began to learn how to chant, I could feel the Lord looking at me, and when I looked up from my booklets, I saw his hand outstretched in blessing, signing his name over me with his fingers. It was a similar feeling to the oft-quoted line from the Presbyterian runner Eric Liddell in Chariots of Fire: When I run, I feel his pleasure. Whether as Teacher or Judge, the gaze of the Lord upon me invokes the same response: Lord, have mercy.

It is a little like the way I came to appreciate the mystagogy of the theology of the Dormition of the Theotokos. Our temple in Richmond is named for the Dormition, though we do not advertise it. We are, after all, in Richmond, and despite our ambivalence about being known as the ‘Chinese mission’ of the Kyivan Church (it really is more of a joke than a reality), the circumstances of our location in a suburb with a population of over 55 percent Chinese means that we do not think that it is a good evangelistic strategy to make our name the ‘death church.’ To the world, we are Eastern Catholic Church Richmond, and the Chinese is even better: Eastern Orthodox Catholic Church. As if having Dormition as our patronal feast were not scandalous enough, our practice as Orthodox-in-communion-with-Rome is advertised in the name, leading over the years to quite a bit of puzzlement among visitors about how we can be Orthodox and Catholic at the same time (and more pertinently, especially among the Latin rad trads, whether we are really Catholic), as well as not a few letters written to us from around the world protesting our identity. We figure that if we are going to give scandal, it might as well be with the joyful humour of who we are as an Orthodox Church in full communion with Rome, not what might appear as the somber tone of the Dormition.

And yet, what we do not advertise in the name, we make up for with content. When I became a regular at the temple in the early days of discerning whether or not I should become a catechumen, I helped to organize an event to experiment with ideas for evangelism. The priest who became my spiritual father said that he wanted to do a workshop on the burial liturgy of our church. Mistakenly, I thought he wanted to put together a discussion group on grieving, but what he had in mind was much better: a walk-through lecture on ‘courageous mourning’ in the Order of Burial. At that talk, he said something that I learned later was one of the key theological themes in his own spirituality: break your détente with death. The modern world, he argued, naturalizes death, even celebrating it and pretending that it is something good through which we must all pass. Death is horrible, he said. It separates us from those we love. Someone might be here one day, and then gone the next. The liturgy for burial deals with all of these themes, revealing death to be the enemy that the Lord came to trample down with his own death. The resurrection of Jesus Christ is the passing from death to life. Death itself is judged by Christ the Judge.

My spiritual father and I both have Cantonese backgrounds, but I came to learn through my mystagogical education that the Dormition is central to the spirituality of the Kyivan Church. I remember finding out that the church that sits atop the Kyiv Caves Monastery is named for the Dormition, and of course that is why I purchased a hard copy of the Primary Chronicle in a futile attempt to find out what the reasoning was. To this day, my half-hearted attempts to read it have yielded only that the church is named for the Dormition, not why it is, although I also know that cathedrals in Vladimir and Moscow also took after this practice. But what was not obvious to me in the more immature days of my early mystagogy gets plainer to me every day. The icon of the Dormition ushers us into what it looks like that the détente with death is broken. Its mystery is that the Theotokos lying there with the apostles gathered around is not all there is to the picture. Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Judge who trampled down death with his own death, cradles his mother as a child in swaddling clothes entering into new life. The enemy has been judged. The chasm between death and life has been bridged. In this way, the catechism of our Kyivan Church, inspired by how our church literally rose from the dead when it came out of the catacombs in 1988 after having been liquidated by Stalin in 1946, is named for the heart of our spirituality: Christ Our Pascha. Christ is the one by whom we pass from death to life, and the Dormition of his mother is the proof of this mysterious reality.

The icons in my beautiful corner tell this story of my journey to understanding the core of our church’s spirituality. It is why I have positioned the icon of the Dormition that my sister and brother Summer and Julian brought back for me from the Kyivan Caves next to that of the Sinai Pantocrator, Christ the Judge. These icons are not reflective of my original orientation to the supernatural. I wanted a tame Christ, a gentle teacher, one who evades the question of death. My entry into the Kyivan Church forced me to confront Jesus Christ as he is, the Judge who tramples death by death and brings his mother from death to life as the firstfruits of our own bodily resurrection. In this way, my icons are not mirrors. They are windows by which the cowardice of my heart is confronted and judged so that I can be courageous in mourning, joining the prayer of my church in her centuries-long meditation on the Dormition her by breaking my own détente with death.

These reflections on the icons in my beautiful corner compose the series I am writing for this year’s St Philip’s Fast in preparation for the Feast of the Nativity, beginning on the Old Calendar as I am in Chicago and switching back to the New Calendar when I return to Richmond in mid-December. They are attempts to account for my process of conversion in the Kyivan Church without discounting the Chinese Christianity of my Protestant past. This post is the fourth.

The previous posts are on the San Damiano Cross, Rublev’s Trinity, and the relation of the Black Madonna to the Oranta of Kyiv.