The Orthodox theologian John Panteleimon Manoussakis has a fascinating passage in his first book God After Metaphysics where he performs a brilliant reading of a moment in Dionysius’s Divine Names:

As you know, once we and many of our holy brethren, as well as James, the brother of God, and Peter, the highest and eldest summit of the theologians, were gathered together to view the God-receiving and life-giving body. At that time it was determined to have all the hierarchs offer hymns to the unlimited power of goodness of the thearchic weakness, according to the ability of each, after having seen the body. Hierotheus, who was also among our divine hierarchs, excelled all the other sacred initiates among the theologians, as wholly outside himself, wholly ecstatic, by “suffering” a communion with what was hymned. He was considered to be a divine and God-receptive hymnologist by all those who had seen, heard, and known him and, yet, did not know him. What am I to say about what was there theologised? For I know – unless I do not know myself – that you have often heard some parts of their divinely inspired hymnodies. (DN, III, 681D-684A).

I’ve taken the liberty of omitting the parts in which Manoussakis provides the Greek, but have kept his emphases. His purpose in quoting this passage at length is to establish a link in Dionysius between hymnody and theology, what (as Manoussakis himself says) ‘Adorno says what he admits that music attempts to “name the Name” and in doing so it is “simultaneously revealed and concealed.”‘ To sing a hymn, in other words, is to do theology, but to do it in a way that both unveils who the One-Who-Is is without doing away with the mystery of the G-d whose essence cannot be grasped.

What is curious, as Manoussakis also points out in his commentary, is that this passage is not about theology proper, in the sense that it is supposed to be about the Divine Name. Instead, it is about the Dormition of the Mother of God:

This passage constitutes a diversion in the narrative that takes us back to an occasion that, according to Dionysius, was none other than the dormition of the Virgin Mary (referred to in the passage cited above as the “God-receiving and life giving body”). It is not clear whether Dionysius claims to have been present at the historical event that took place in the first century or is simply describing the liturgical celebration of the feast of the Assumption (which, in according with the temporality of the kairos, “re-presents” the events that are celebrated as occurring always “today”). Given the recent emphasis on the liturgical understanding of his theology, I think it would be safe to assume the latter. (Manoussakis, God After Metaphysics, p. 109-110).

The moment that Dionysius is recounting, in other words, describes how the hymns to the Theotokos on the occasion of her falling asleep brings the singers back to that very moment. Theology is not merely descriptive. It is transportive. Through the music of the liturgy, those celebrating it are brought to the actual theological moment, the moment in which G-d is revealed, usually through the material world and often beyond words. The time here is described by the Greek word kairos; it is the in-breaking of sacred time in chronological history. In the kairos of Dormition of Mary Godbearer, the One-Who-Is reveals himself as the risen Christ in whose resurrectional life we partake. Mary is asleep, but she is already born again into new life before the face of G-d, a sign of our future when we too will fall asleep in the Lord. She is the dead that has not died but is risen into eternal life, and so are we in Christ. Dionysius may not have been at the hymning of that sleeping body in chronological historical time, but he was also really there in the liturgy where hymns are sung that affirm the communion of all Christians with that body. He is there, and we are too, if we celebrate the Feast of the Dormition.

At the Eastern Catholic Church in Richmond, the Dormition is our patronal feast. Most of us are a little shy about advertising that fact, though. We are a neighbourhood church in Richmond, not an ethnic enclave, and in reaching out to everyone in Richmond regardless of their ethnicity, we have to be realistic about the reality that Chinese people make up over fifty percent of our city. Unless they are already Catholic in the Latin Church (there are even fewer Chinese Orthodox in our town), not many of them would have an appreciation for the falling-asleep of the Mother of God and her birth into resurrectional life. To most Chinese people, being named for the Dormition would mark us as the ‘death church.’ It would be as bad as if we had a big ‘number four,’ the homonym for death in most Chinese languages, painted outside our building. We may not believe in such superstitions, but we would also fail in our evangelization if we couldn’t get most people in our city, including the superstitious ones, to darken our doors. We therefore emphasize to Richmond who we truly are. We are an Eastern Catholic Church, and in Chinese, our name is the Eastern Orthodox Catholic Church, as we know from our history and ecclesiology that the Greek-Catholic Church of Kyiv is, in the words of our Patriarch Sviatoslav, ‘the largest of the Eastern Catholic Churches’ and ‘not in any way opposed to the Orthodox Churches,’ as we ‘are an Orthodox Church, with Orthodox theology, liturgy, spirituality and canonical tradition that chooses to manifest this Orthodoxy in the spirit of the first Christian millennium, in communion with Rome.’

But shy as we may be about the word ‘Dormition,’ our deeds demonstrate much more than our words. Every year on the eve of the Dormition – including last night – we serve Festal Matins with the Sacred Order of the Holy Burial of our Most-Holy Sovereign Lady, the Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary. As part of this service, we sing the Lamentations to the Theotokos with the same melodies from Jerusalem Matins during Great and Holy Week, the service where we lament the death of our Lord Jesus Christ and participate in the burial of his body. As we are at the graveside of our Lord after he had suffered his Passion, we now stand before the grave of his Mother, singing similar hymns; in the opening words of the first stasis, In a grave they laid You, O my life and my Christ: And now they lay also the Mother of life, a strange sight to heaven’s angels and to men. This identification between the burial of Christ and the dormition of his Mother is the moment of kairos that Manoussakis finds in Dionysius’s account. The lamentations we sing transport us back to the theological moment of the Dormition itself – of Mary’s birth into the risen life of her Son – and thus the temple whose name we are shy to pronounce in the midst of a Chinese ethnoburb becomes the site of the Theotokos’s burial in real time all the same.

This moment of kairos drives a wedge between the superstitious and the supernatural. We bless flowers and herbs because the tale of the Dormition features the Holy Apostle Thomas late again for the burial and discovering the next week that Mary’s tomb no longer contained a body, but flora and fauna. The rubrics allow for the Lesser Blessing of Water, which is fortuitous this year because we are planning to have a baptism later this week and have run out of holy water from our Theophany celebrations because a member of our temple seems to have drunk all of it. This person is Cantonese, and for all of my celebration of the martial ethics and literary sensibilities of us Cantonese people, one of our enduring vices has been our superstition. Both words and material in the natural order become emblems of fortune. They are not merely symbols; they are omens – the number ‘four’ for death, ‘eight’ for prosperity, the arrangement of houses and landscapes according to the geomancy of fengshui to maximize luck and master death. My friend is a Christian in the Protestant tradition discerning whether Eastern Catholicism is right for him, and his religious identity indicates that among us Cantonese, theological identification has nothing to do with being superstitious: there is a superabundance of ‘eights’ in the parking lots of most Chinese churches in our city and a dearth of ‘fours.’ In the case of our holy water drinker, the superstition is that holy water will give him good luck in his business and love life, and as much as we explain that what he is drinking is in fact the water of baptism by which we are transferred back to the moment of Christ’s immersion in the Jordan, he seems unable to see reason.

But in this difficulty with our temple’s holy water drinker, our local evangelistic task is revealed. We might not say the word ‘Dormition’ very often for the purposes of evangelism, but our liturgical actions reveal that we are not afraid of being the ‘death church.’ As my spiritual father often says, we have broken our ‘détente with death’: we do not accept death to be the final reality, and we do not fear to speak of it, because we are Christians, which means that the Spirit of the One who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in our hearts. In the body of Mary, the victory of the risen Christ is revealed in our human bodies. In our yearly visitation to her grave, we are a sign to Richmond that there is a difference between the superstitious and the supernatural. Superstition, it can be said from the practices of avoiding death and maximizing fortune, is the attempt to manipulate the more-than-material qualities of the natural order. The supernatural, on the other hand, is a word that simply conveys that that natural order has never been ‘pure nature.’ As the theologian Henri de Lubac SJ puts it, le surnaturel describes the Christian assertion that the material world is sustained by the One who created it. The risen life unveils this supernatural constitution of the world in which we live. Its realities are not to be manipulated; they are to be discerned for the deepest truth that constitutes them, and the truth is that death is not the ultimate reality – the resurrection is – and therefore should not be feared, avoided, or tricked by geomancy.

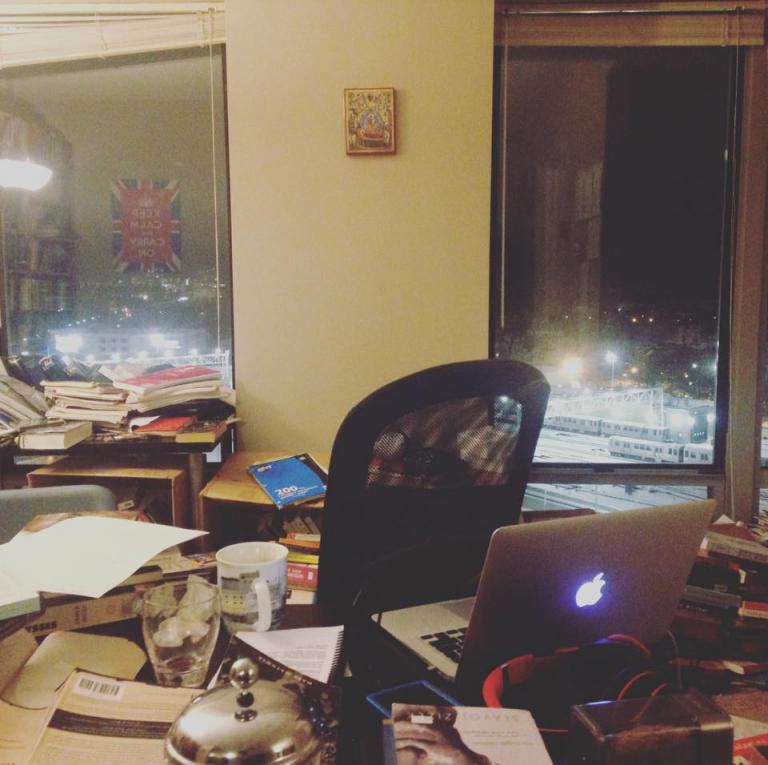

In that spirit, I acquired an icon of the Dormition earlier this year. It is now in my beautiful corner, but my first impulse was to put it in a place in my home office where it overlooks my messy table and even messier floor. I don’t feel bad about having moved it, as my icon corner currently also overlooks my entire office, and if what I have said about the Dormition in the foregoing paragraphs is true, then it is one of the theological keys that unlocks the statement that my icons collectively make. But after I placed the Dormition in its initial spot, I took a picture and posted it to my social media. A deacon in our church commented that in its place, she throws over her mantle in maternal protection over me and my work. That reflection, I reflected, was a curious one because the icon of the Dormition is quite unlike the one of her Protection; it does not feature her taking off her mantle to protect the city, but instead herself in swaddling clothes cradled in the arms of her Son. But as I have thought it over, that formulation makes sense because the precondition of the Protection of the Theotokos is her rising to new life in her Dormition. By extension, our celebration of her as our Sovereign Lady, the Immovable Wall, and the one who throws her mantle over us in protection extends the supernatural reality of her resurrectional life. These names we have for our Mother, and our cries to her for deliverance from trouble, are also not superstitious because they are premised on the kairos of the Dormition. They are the words we have instead for the discernment of supernatural reality, the truth that our ultimate reality, like that of Mary Godbearer, is to rise from the dead and to stand before the face of the God whose life sustains the world in which we live.

Last year’s set of fifteen reflections on the Dormition can be found here. As the news about the sexual abuse in the Latin Church has been spreading like wildfire on their Feast of the Assumption, I plan to address it in future posts, though I also addressed it in that series last year during the Dormition Fast. I am not sure that I know how to engage the poignancy of the revelations being unveiled on the eve of their feast, but this is a reality that they as a church sui juris must reflect upon on their own, as Simcha Fisher has.