When I ask my wife what’s new, she generally responds: “What’s new pussycat?”

When I ask my wife what’s new, she generally responds: “What’s new pussycat?”

Tom Jones, the singer or the novel, she says are both hot and cool.

Plato’s Euthyphro? Her reaction is different: informed but substantially less passionate. Why?

The Platonic dialogue recognizes that truth cannot be both hot and cool, that being a contradiction*. In fact, the dialogue insists on being merely immortal: the book of the hepcat. The opening question is:

What’s new, Socrates, to make you leave your usual haunts in the Lyceum and spend your time here by the king-archon’s court? Surely you are not prosecuting anyone before the king-archon as I am?**

The dialogue will center on piety. Should a son prosecute his father? If he must do so, then should he be as cocksure as Euthyphro is? After all, some moral choices are hard: two important goods are in competition and the demands of both cannot be honored. We should honor our parents, but also seek justice for all. When the desire for justice conflicts with our duty to parents, a good person will pause, agonize, and then seek justice for everyone.

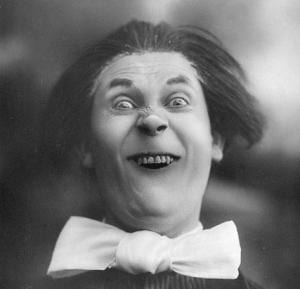

Only a moral lightweight, a pussycat or tomcat, would be light about the choice. These are folk driven by immediate passion at the expense of the greater good. There is nothing wrong with passion, God help those who do not know passion. Instead, the difficulty is prioritizing the passion today against the passion of yesterday or tomorrow. If a man throws away his shot, then future chances cannot be used!

A hard choice that is taken lightly shows that the person choosing is morally bankrupt. They may choose correctly, but they miss the weight of the other side. When we make hard decisions easily, we show that we have not understood one side of the moral argument. Suppose we (generally) claim that good parents should get respect AND we assume that no matter who is guilty the unjust must face justice. Too quickly, easily, with little reflection, throwing our mom and dad to the wolves of justice shows that we were not serious about one moral claim. A hard choice is easy only if we do not feel the force of one of the choices.

Leave aside the “jerk for justice,” that Euthyphro has become. What is more troubling is that Euthyphro is more interested in what is “new” (for the pussycat or the tomcat) rather than what is just, good, or beautiful for both. The ways these eternal truths are manifest can change, we should look to those differences, but the deep truth endures.

Socrates has come to the courts, where he is not usually found, and Euthyphro wants to know why. What is new?

Nothing is new except the incidentals: the just man has once again been hauled short by injustice. Nothing is new about the hepcat being persecuted by the squares.

Socrates has known himself and so never comes to a place randomly or merely because that place is “new.” He goes where he must, where he wishes, because this is the right thing to do. If you ask why he is there, then you do not know Socrates. For a so-called friend to ask this question shows a defect in friendship. If you know Socrates, really know what is happening in his life, then you will know why he has been forced to be in that ugly place. Socrates is on trial: on his way to execution by the Athenian state.

There is nothing new about injustice, nothing new about why Socrates would be on trial. Good men and women are always put on trial by a tyrannical state for standing for the good, truth, and beauty.

Beware a mistake that we might make. The trendy seeks “what is new,” yet the reactionary is no better when he pretends what is old is always superior. If the dialogue were to begin: “What has been? What was normal yesterday?” this would be just as useless and dangerous. The new usually is part of old patterns and the old has elements (like Socrates being in court) that are new. Why is Socrates in court? That is a fair question, not because of the novelty, but because of the nature of the event: being in court is dangerous!

We should love what is happening now, because that is part of reality. We must not forget what has happened, because the past cannot change. One need not be a square, a reactionary, to get it. Instead, one can be the hepcat: the person who is cool with all the coolness from centuries past to millennia future.

Euthyphro is a dialogue between the pussycat and the hepcat. The cool person of today, now, is like the hepcat, the person who is cool from age to age, in some ways. The pussycat will seize the day, but miss the centuries, while the hepcat will embrace all the goodness, truth, and beauty of all ages. The prude, the narrow, the square will miss what is happening now and what happened then and what will happen tomorrow.

What’s cool pussycat?

Rather: what’s good, true, and beautiful hepcats?***

——————————–

*And yes, I am guilty of an equivocation. Tom Jones would use “hot” and “cool” in a different way that Plato. That’s the fun of an informal essay: making small verbal jokes. (Adult children say: “. . . very small.”)

**Plato. Plato: Complete Works. Euthyphro 2. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

***I am thankful to Professor Al Geier for this term. Hope is certainly a hepcat.