David Russell Mosley

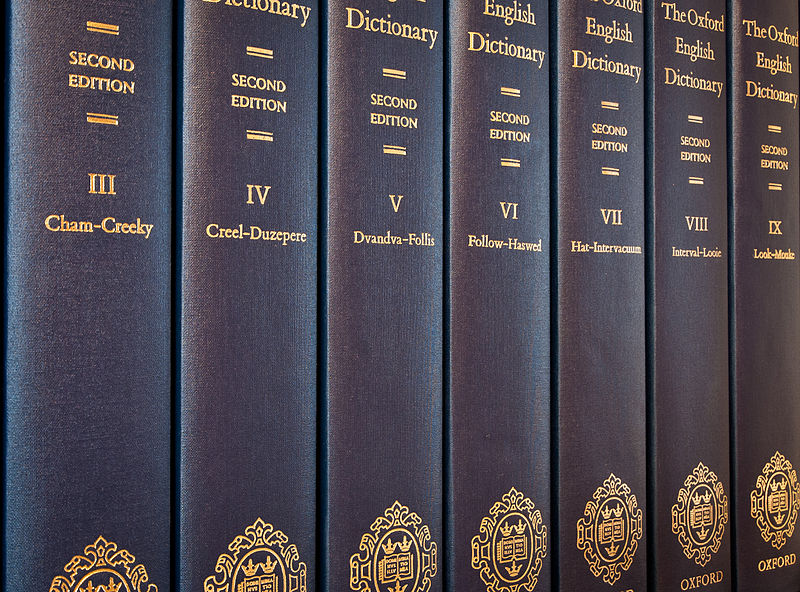

English: Volumes of the Second Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary

Date 21 April 2012, 09:29:48

Source https://www.flickr.com/photos/mrpolyonymous/6953043608

Author Dan (mrpolyonymous on Flickr)

(CC BY 2.0)

Ordinary Time

2 October 2016

The Edge of Elfland

Hudson, New Hampshire

Dear Readers,

Over at A Little Bit of Nothing, fellow Patheos Catholic writer, Henry Karlson examined the nature of atheism. Karlson argued that atheism is a kind of delusion since all people have some kind of absolute (a grand, unifying theory, for instance), and yet atheists claim to be certain that there is no absolute, no God. There is more to Karlson’s argument and you should really read it for yourself. In response to Karlson’s post, Luciano Gonzalez, author of the Patheos Atheist blog Sin God, wrote that Karlson was being imprecise with his terminology (again, there is much more to Gonzalez’s argument and you should really read it for yourself). The argument, in so much as there is one, between both men is over defining terms. So, I thought I would throw my proverbial hat into the proverbial ring and attempt some definitions.

God

Perhaps the most ultimate word that needs defining here is the word God. As Karlson is using it, the word God since means the Absolute, the ultimate existent thing. Karlson is not arguing, yet, for a Christian understanding of that Absolute, merely that God can be used as a placeholder for whatever we hold to be Absolute. The Absolute could be the Universe, an impersonal but active force, a personal God, etc. Karlson is in many ways utilizing the technique of David Bentley Hart (though I haven’t asked him if Hart stood behind his arguments at all or not) by describing God at the most basic level. Hart begins with Classical Theism, Karlson begins with the Absolute. In any event, the point is to know what it is we are arguing about. For Karlson it is the Absolute.

Delusion

Gonzalez takes issue with Karlson’s use of this word because he believes it will not foster good will and respectful dialogue between atheists and theists. This would certainly be true if Karlson meant it pejoratively, but there’s no real evidence that he does. Rather, Karlson means it quite literally, he believes atheists delude (or deceive) themselves when they claim with certainty that there is no Absolute (perhaps because in making this claim, one claims that the lack of Absolute is the Absolute, although Karlson does go on to argue that making this claim makes the claimer the Absolute as we’ll see with the next term). Ultimately, I think the issue over this word is that it is a technical word, appropriately used (for Karlson’s argument) that sounds pejorative. It is like being called ignorant when one does not know something. The truth of the matter is when you don’t know something you are ignorant of it (that is you are un-knowing––in-gnor(are)––about it). Still it doesn’t sound nice to be called ignorant, even if it is technically true.

Self-Theosis

I only bring this up because Gonzalez made such a point of noting that Google did not recognize this as a word. Gonzalez offers instead apotheosis. The problem here is that Karlson is using the recognized word theosis (Greek for deification) and suggesting that when we deny the existence of the Absolute we in essence claim that we are the Absolute (since we know with certainty that no Absolute exists). Apotheosis is more commonly used for the deification of Roman Emperors or Greco-Roman heroes. Yes they might put some of it about themselves, but they are not deifying themselves, the gods are deifying them. Self-theosis (which I actually call auto-theosis in my dissertation) means that someone or something is attempting to make itself God, not that it is being made God by external forces.

Atheism/Agnosticism/Agnostic Atheism/Gnostic Atheism

The crux of Gonzalez complaint against Karlson was a misuse of the word atheism. Karlson used that word to mean a denial of the existence of the Absolute. Gonzalez rejects this oversimplification suggesting that what Karlson means is gnostic atheism. Now gnostic means knowledge, although it also carries overtones of secret knowledge and dualism thanks to the ancient Gnostic sects (such as the Manichaeans). A gnostic atheist, according to Gonzalez (and other sources) is one who disbelieves in God (atheist) and is certain there is no God (gnostic). Gonzalez, on the other hand, is an agnostic atheist. He believes there is no God (atheist) but is not certain of that fact (agnostic). But here’s the problem, Gonzalez’s specialized use of these words is rather newer than Karlson’s. Karlson’s use of atheism dates back to the sixteenth century, whereas agnosticism (traditionally defined as the unknowability of the existence of God) dates back only to the nineteenth century and was formed, in part, to distinguish those who disbelieved in God and those who were uncertain of God’s existence. Once we did get the word agnosticism, however, it began being applied to varying kinds of atheism, including notions of implicit vs. explicit atheism. Gonzalez argues that his use of the words is the norm amongst atheists whereas Karlson, as a theologian, believes his own use the norm.

Now, it is true that I generally agree with Karlson. I believe his use of the word God as well as atheism are the standard ways in which the common person understands them. It is good to know that there are atheists who wish to further subdivide their understanding of atheism and now knowing that this should help people like Karlson and myself when discussing these ideas with them. Nevertheless, it is important for both sides to understand how we are using the words we use. Only when we can come to the same definitions of a word (even if we disagree over the reality of said word) can we actually have meaningful dialogue.

Sincerely,

David