David Russell Mosley

Eastertide

24 April 2018

The Edge of Elfland

Manchester, New Hampshire

Dearest Readers,

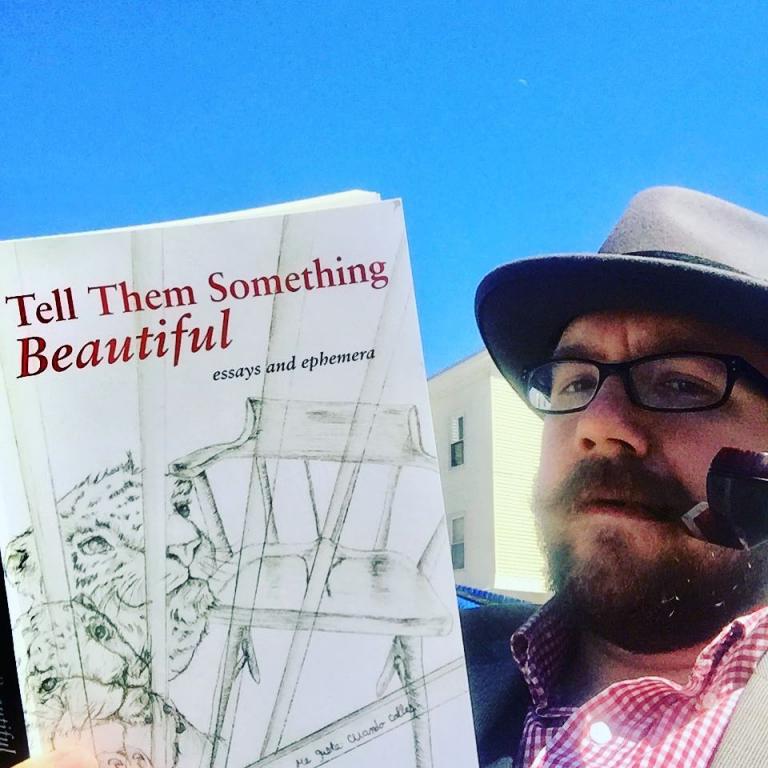

To say I read Sam Rocha’s Tell Them Something Beautiful would be incorrect. I devoured it like a man who hasn’t eaten in weeks. I ravished it like a husband who sees his wife for the first time after a long absence. I will need to return to this book to savor it, fortunately, it is a book that will bear re-reading.

I write this review with something of a smirk. When Sam’s Folk Phenomenology came out he let people know he was looking for reviewers. I offered, received my copy, and still have neither reviewed nor read it. You can believe, however, that it has moved higher up on my to read list now that I’ve read Sam’s collection of essays.

Tell Them Something Beautiful is subtitled Essays and Ephemera as it is composed of essays and blog posts Sam has written over the last 8 years or so (actually, I think it is closer to 6 or 7, the oldest I can recall is from 2010 and the most recent from 2016). Sam organizes many disparate––and some interconnected––essays around four foci: Discontents and Diagnosis, the Ordo Amoris, Teaching as Deschooling, and Funk Phenomology. Despite the essays being written at different times and in response to different cultural events, or simply occasioned by whatever struck him that day, Sam masterfully and intentionally lays them out in a way that leads us to a certain end. There seems to be something Sam desperately wants us to understand: death.

I first realized this when I read Sam’s essay “A Curriculum of Life.” Here Sam lays out his plans for deschooling his children, especially Tomas who was around 5 or 6 when the essay was first written. Toward the end of the essay, Sam asks, “But when do we prepare for life and death? For theosis?” As one who has written and published on the subject of deification I had to stifle a loud “Yes!” when I read this line. Education is meant for human formation, not to the end of finding a job but for the Beatific Vision. And of course, for most of us, we will not get to the Beatific Vision, to deification, without the help of Sister Death, as St. Francis called her.

Philosophy as Sam and Pierre Hadot would remind you is a way of life. And as Socrates would tell us, the way in which Philosophy is a way of life is precisely in the fact that it prepares us for death. In the Epilogue the penultimate section of the book and the true end––the interview with Sam (which is excellent) being a true appendix, something material but appended from the rest––Sam gives us a talk he did reflecting on the very recent death of a student he was supposed to meet and never did. “Tragedy,” writes Sam, “suffering, loss, and more: in these dark moments of wisdom we find what love is, a love more durable than the hobbies of liking, an eros that extends beyond enjoyment.” When Mossy nears the end of his journey in “The Golden Key” by George MacDonald, he has a conversation with the Old Man of the Sea:

“You have tasted of death now,” said the Old Man. “Is it good?”

“It is good,” said Mossy. “It is better than life.”

“No,” said the Old Man: “it is only more life.”

Sam understands this and this, I think, is the guiding principle behind all of Tell Them Something Beautiful. This is seen poignantly in the final titled section of the book, Funk Phenomenology. Here Sam wants us to see the funky side of reality. And while this does mean music and rhythm, it also means bad smells, earthiness, materiality, tragedy, death. There’s a reason, after all, we talk about the funky smell coming from the fridge. It is not unrelated to the funky sound coming from funk music. Think of a bass being slapped (a form of bass playing I never quite learned) and you will see what I mean. A slapped bass is a bass played violently. You strike the strings, you pull them up away from the neck, allowing them to strike down hard. This is not neat or gentle playing (for which, of course, there is room). This is what Sam asks us to see, the hard parts of reality, death, but to know that, somehow, death is baptized, transformed, not in some saccharine way where there are no tears, no blood, no mourning, but in a way that allows us to call Death our sister and yet to recognize that our experience of her can hurt like hell.

There is more I could say about this book, but I will leave it to other readers. For me, this book was necessary. I needed these reminders especially as a theologian, a teacher, and most of all as a father. All I can say now is, read this book.

Sincerely,

David