Ordinary Time

29 January 2018

The Edge of Elfland

Concord, NH

Dearest Readers,

The Catholic Church is currently going through a dark time, of this there can be no doubt. But in the midst of this darkness, I don’t want to forget the things that drew me to the Catholic Church in the first place. Over my next few letters, I’ll be writing about what drew me to the Church which hasn’t changed despite the mess we have found, and often put, ourselves in. Today, I want to focus on the Church’s ability to be particular and universal.

Recently, through a BBC Scotland video, I learned that 2019 is the UN’s Year of Indigenous Languages. I love this. I have often thought that one of the major problems with the UK was not, necessarily, the attempt to unite 4 countries under one crown, but the early attempts to homogenize their cultures, usually by way of making them all English. Allowing the Welsh to be Welsh, Irish to be Irish, and Scottish to be Scottish seems the best way to ensure both a greater sense of cultural identity while also existing as one country. Properly encouraged, there ought to be a greater sense of unity precisely through the diversity. But I digress.

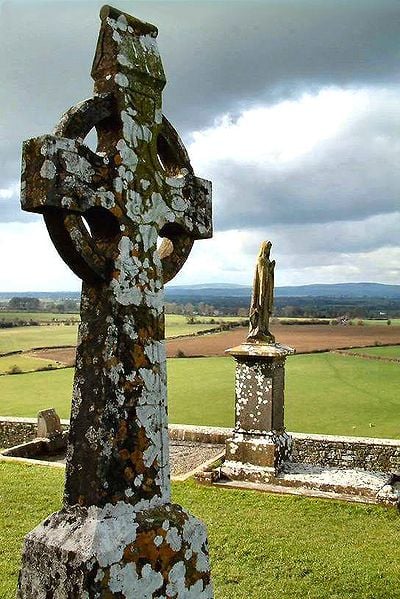

While my interest in Scots, Gaelic, Welsh, etc., is, at the core, an ancestral one, these languages and their cultures also reminds me of something beautiful about the Church. We are particular as well as universal. Just as various nations around the world have indigenous peoples with indigenous languages and cultures, so too is the parish life of the Church unique in the various cultures where it can be found. Here in New Hampshire, for example, we have a large number of French-Canadian and Irish churches, built by the immigrants who came and settled here. St. Patrick’s in Nashua, NH is an interesting church for it has never, according to its current pastor, not had an Irish priest.

Sadly, this sense of particularity can lead to darkness. In Manchester, NH there is a church called Ste. Marie’s. It is massive, and ornate in its architecture. Local history has it that the church was built as a French-Canadian cathedral and was meant to have its own bishop. This did not happen because there was already a cathedral for the diocese in Manchester. What animosity there may have been I don’t know, but people born and raised here have often told me that there were struggles between the Irish and the French-Canadian Catholics. And this is not peculiar to New Hampshire, nor to New England. There have been times, and in some places, those times still exist, where people of one culture, and thus one expression of the Church, did not/do not have anything to do with those of another. Whether it was the Irish against the Italians, both against the Poles or the French, time and again have we seen how a slavish devotion to the particular leads to a rejection of the universal. Yet, I do not think this must be the case.

Proper love for the particular requires love for the universal. We cannot properly love our parish if that love does not come from the Church Universal. But so too, love for the universal must be based in love for the particular. If one only loves an idealized form of the Church and not the local parish, this is a problem. This is why, sometimes, I think the Western Church was wrong to focus on making people cultural Romans as well as Christians. The desire for uniformity, which itself is understandable, after all there is, “One Lord, one faith, one baptism,” I think often led to the removal of local beauties. But, as has been seen in some of the Eastern Churches (both Catholic and Orthodox) the desire to be locally applicable has sometimes led to individual parishes unwelcoming of those from a different ethnic or cultural background. How do we reconcile these two tendencies in the Church without resulting in either liturgical colonialism or liturgical nationalism?

The answer lies somewhere in the middle. The Church is large enough to hold within it many expressions of the one faith. Yet we can never forget that all our individual cultures and expressions of that faith belong to something larger. The Church needs to reclaim these two modes of its own expression. We cannot and should be not be afraid of particular expressions of the Church. These should be celebrated. Whether we’re talking about the Mexican dia de muertos or the English Lammas Sunday, all these and more should be encouraged in local communities. And yet, we should not let our various cultures forget that we belong to one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. We must remember that universality for us means precisely a host of particularities united in the Eucharist. The Church catholic is the Church everywhere and thus in every kind of expression. This does not and should not mean that absolutely anything goes or that there are no guidelines or rubrics that can or ought to govern us, but even these have variety. There are 24 rites of the Catholic Church and even these can and will breakdown further as you become more local. Different saints get different emphases in different areas, and this was often how it went. Local cults rise up and then with the rise of pilgrimages local saints become national or international saints, yet they will still be of particular importance in the land where they first were venerated. The particular leads out to the universal and the universal returns to the particular.

And this is one of the many reasons I became Catholic, because the Catholic Church has the ability to hold the particular and the universal in proper proportion. It does not always succeed at this, but this does not mean we should stop trying. If anything, we should encourage more particularity, more individuality that is rooted in the universality of the Church Catholic.

Sincerely,

David