Eastertide

St. George’s Day 2019

The Edge of Elfland

Concord, NH

Dearest Readers,

Today, as many of you know, is the feast day of St. George, parton, amongst other things, of England. It is also the possible birthday and definite death-day of William Shakespeare. In many ways, today is a profoundly English day, which does my anglophilic heart good.

While I’ve long known of St. George, my first introduction to him was as the Knight of the Red Crosse in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene. Here, George is completely removed from his Cappadocian origins and is made a man raised by the elves. Spenser sends him with the Lady Una to defeat a dragon ravaging her land. Much later I learned the true story, or as true as we can tell. I like that there isn’t just one version of the St. George story. His story transcends particular contexts and yet precisely because of this always becomes inherently particular. His veneration is widespread and yet differs slightly depending on context. The English flag is the red cross (which Spenser blazons on his armor and shield) on the field of white. In Shakespeare’s Henry V, Henry calls out, “The game’s afoot: follow your spirit, and upon this charge cry ‘God for Harry, England, and Saint George!’” So George is profoundly English to the English. Just as he is profoundly Greek to the Greeks and likely Italian to the Italians, etc. He transcends his particularity only to placed back into a particularity. And this is beautiful, so long as we don’t confuse our understanding with the totality of reality. The English George likely tells us things not fully discernible in any other one story, but it does not tell us the whole story either.

Speaking of Shakespeare, readers may know that for three years I lived in England. What you may not know is that nearly eleven years ago I visited England for the first time. During that trip, which has proven formative for me, I had the opportunity both to visit Stratford-upon-Avon and to see a production of The Tempest at the Globe Theatre in London. Sadly, all that sticks in my memory from Stratford is seeing our Irish tour guide climb a statue of one of Shakespeare’s fools and walking through the house Shakespeare may have lived in or been born in. I can’t recall which. The production of The Tempest sticks more clearly in my mind.

Two friends and I endeavored to get tickets but could only get one seated ticket. So two of us got our groundling tickets and stood for the show. Since the Globe is an open air theatre, we got a little wet when it rained part way through the show. While the costuming and setting were both traditional, there were a few differences between this and other productions of The Tempest. First, it was an all-male cast, harkening back to the productions origins when all plays were done with an all-male cast. But this had an added difference, there were only three men. Sadly, at the time, I had never read or seen the play before. So I struggled to keep track of who was who and when. One of the characters who mostly played Ariel and Miranda often wore or removed a kind of ruff depending on which character he was. Sadly, part way through, the ruff was mislaid, and so I had to try to listen for the change in his voice to tell who he was. The third unique feature of this play was the use of an all-male choir, who would sing throughout different parts of the play.

I took little enough away from the play. I didn’t understand the plot, I was never sure who was who, and I often focused more on the rain or the pain in my legs from having to stand in the open air. And yet, the experience was overwhelmingly positive. I walked away with a greater respect both for sixteenth/seventeenth century actors and audiences. I walked away with a greater love for the English language. I walked away with a greater love for England itself. My anglophilia, which was already present, grew exponentially that day.

And yet, just like St. George, Shakespeare is not limited to English soil. His works transcend particular circumstances, particular places and ages. This is why Shakespeare’s works can be adapted to so many different settings. This is why 10 Things I Hate about You can be an adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew without using the original language and yet still recognizable. This is why Romeo and Juliet can be translated in scene and age to modern California and yet retain the original dialog. Readers, viewers, and actors of Shakespeare’s works know that even though many of his plays are not set on English soil, they remain profoundly English. And yet, they can be taken so far afield and as to be played as if they really were set in Italy or Cyprus or Greece, and not England wearing fancy-dress.

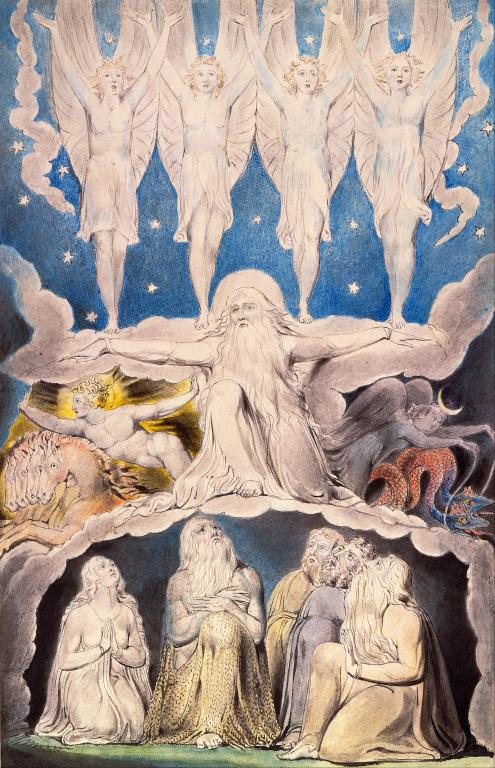

This leads me to a final reflection, one that often comes up in my classes. Jesus and Mary, as well as saints such as St. George, have often been depicted as though they belonged to the culture in which they are being depicted. My favorite example of this is the blonde-haired, ginger-bearded Jesus of the Book of Kells. Jesus was, and remains biologically, a Palestinian Jew of the first century. And yet, his Gospel was not just for Palestine nor for the first century. He is more universal than that, precisely because he is particular. But, and this is key, we can never forget his historic particularity. This is the problem so many, especially here in the United States, have. We forget that because Jesus is depicted in our statues as though he were of European descent that he would have looked profoundly different from those of us who are. We forget that he would have looked more like those we too often label terrorists than those we often see in our parishes. There is a line in the film, A Knight’s Tale, I have always loved. As the main characters are drinker in a French pub they are being challenged by a group of French knights. The fight gets to a point where, to sing their praises, the French note that, “Even the pope himself is French.” To which one of the English characters responds, “Well, the pope may be French, but Jesus is English.” This is where we go wrong, when we think that Jesus or Mary or St. George or even William Shakespeare belong only to us and not to the others. They can be profoundly ours in a profoundly special way, but only if we can remember that they are not our slaves, we do not own them. They have, in a sense, chosen to belong to us, but only if we’re willing to share.

Sincerely,

David Russell Mosley