There’s a long-standing debate over whether we humans are naturally predisposed to believe in the supernatural, or whether it’s learned. Well, here’s a study that shows the importance of young children’s environment in determining credulity.

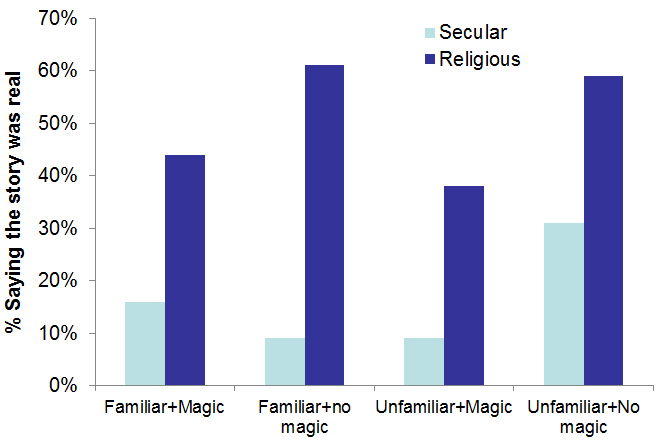

The basic set-up was simple. Kathleen Corriveau (Boston University) and colleagues recruited 33 kindergarten kids in the USA (that’s 5-6 year olds). Half went to state-run schools, which are mostly religion free, while the other half went to schools run along Christian lines. The state-school kids all came from non-churchgoing families, whereas the kids from religious schools all came from churchgoing families.

Then they read them a series of stories, loosely based on magical stories from the bible, but carefully disguised. They varied these stories so that sometimes they referred to magic, sometimes not.

Just to be sure of it, sometimes they changed the story a bit so that it was unfamiliar, and not recognisably biblical. For example, here’s the variants they told of the ‘Moses parting the red Sea’ Bible story:

Familiar+Magic

This is John. John led his people when they were escaping from their enemies. When they reached the sea John waved his magic stick. The sea separated into two parts, and John and his people escaped through the pathway in the middle.

Familiar+No Magic

This is John. John led his people when they were escaping from their enemies. When they reached the sea John waved his stick. The sea separated into two parts, and John and his people escaped through the pathway in the middle.

Unfamiliar+Magic

This is John. John led his people when they were escaping from their enemies. When they reached the mountain John waved his magic stick. The mountain separated into two parts, and John and his people escaped through the pathway in the middle.

Unfamiliar+No Magic

This is John. John led his people when they were escaping from their enemies. When they reached the mountain John waved his stick. The mountain separated into two parts, and John and his people escaped through the pathway in the middle.

The point was to try to see what cues lead these children to decide if the story was fantasy or reality. Importantly, at no point did any of the stories mention God or divine intervention.

As you can see in the graphic, the secular kids were much less likely to say the stories were real. They could pick up on the cues in the story, and figure out that it must be fantasy.

As you can see in the graphic, the secular kids were much less likely to say the stories were real. They could pick up on the cues in the story, and figure out that it must be fantasy.

And they could do that at aged 5-6!

It’s critical to realise that both groups of kids – religious and secular – knew the difference between fact and fantasy. Both groups could recognise real versus fictional characters.

And although this was a small group, it mirrors what they saw in an earlier study, in which religious kids (whether churchgoing or non-churchgoers attending a religious school) said religious stories were real and also were more likely to say that non-religious, fantasy stories were real.

The authors conclude that the reason the religious kids were more likely to believe that these stories were real is that they “have a broader conception of what can actually happen”.

Now, what this study doesn’t tell us whether a religious upbringing makes kids more credulous, or a secular upbringing makes them more sceptical.

But it does show that critical thinking is crucially influenced by environment, and from a very early age.

![]()

Corriveau, K., Chen, E., & Harris, P. (2014). Judgments About Fact and Fiction by Children From Religious and Nonreligious Backgrounds Cognitive Science DOI: 10.1111/cogs.12138

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.

This article by Tom Rees was first published on Epiphenom. It is licensed under Creative Commons.