You may have seen the buzz around a recent study which found that kids in atheist families are more altruistic than kids in religious families. Like any study that reinforces preconceptions of a vocal group, it was social media gold dust.

I want to take a critical look at it and some of the objections that have been raised in recent days. I think the attacks are off mark: this is a robust study, at least by the limited standards of most social psychology research! But there is something that complicates any attempt to interpret the findings – I’ll explain what later.

The study itself was dead simple. The researchers (led by Jean Decety of the University of Chicago) gave 1,170 kids aged 5-12 years a bunch of stickers (they could chose their 10 favourite), and told them that the stickers “are yours to keep”. The kids were local school kids in six different countries: USA, Canada, Jordan, Turkey, South Africa and China.

The study itself was dead simple. The researchers (led by Jean Decety of the University of Chicago) gave 1,170 kids aged 5-12 years a bunch of stickers (they could chose their 10 favourite), and told them that the stickers “are yours to keep”. The kids were local school kids in six different countries: USA, Canada, Jordan, Turkey, South Africa and China.

Then they explained to the kids that not everyone in the school would be getting stickers (there was not enough time, they said). But, if the kids wanted to, they could put some of their stickers in an envelope to be shared with the others.

This is a cunning version of something called the ‘Dictator Game’, which is widely used in psychological research. How much of your own stuff will you give away, even if no-one will ever know how generous you were?

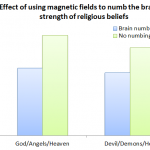

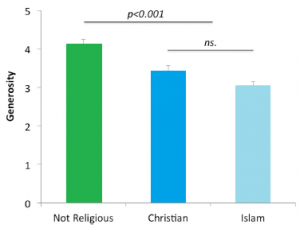

On average, the kids with atheist parents gave away 4.11 stickers while the kids with religious parents gave away 3.25 stickers. This was highly statistically significant, even after controlling for the mother’s education status and for difference between countries.

So let’s take a look at what the critics say

I’ll dissect the efforts of one Christian (George Yancey, writing at The Stream) and one atheist (Matthew Facciani, writing here on Patheos) – they’re pretty representative of what the naysayers are claiming.

Both pick up on the Dictator Game. This is a fascinating topic because hundreds of studies using the dictator game have revealed a totally unexpected finding: we humans tend to give stuff to our fellow humans even when it’s done completely anonymously.

That doesn’t make sense from an evolutionary psychology perspective. People that give stuff away without any payback are going to lose out in the evolutionary struggle. Yet most humans do it, at least in a lab setting.

Now, there’s a ton of papers discussing why that might be, but explanations tend to revolve around the idea that altruism is programmed into us by society. Cultures that encourage altruism are successful. It would not be the first example of people doing illogical things as a result of social programming.

Both George and Matthew land on this as if it undermines the results of the study. They both cite the same paper showing how altruism in the ‘Dictator Game’ might be a result of conforming to social expectations under the watchful eye of the experimenter. But that does not undermine this study, nor any of the other studies that have found religious people are more altruistic (under certain circumstances) in the very same Dictator Game.

What it shows is that kids in atheist families are either brought up with greater social expectations of altruism, or are more sensitive to and aware of cultural norms around altruism. It might explain why they are more altruistic – but it doesn’t take away from it!

Both also pick up on the fact that the analysis didn’t statistically control for many factors. George’s critique is a bit bonkers (he wants controls for maternal education and religious attendance – both of which actually were assessed).

Matthew wants controls for ‘inequality’ – although of course maternal education is already a robust measure of both social status and income. He also wants to measure race and ethnicity, although these would be meaningless in a cross cultural study such as this (being black in Jordan is a totally different kettle of fish from being black in Chicago).

When people don’t like the results of a study, they usually call for more control variables – if only X, Y and Z were controlled for, you would have observed something different. But really, this over-states the power of statistics to correct for imbalances. Often it can just make things worse (if the variables are interconnected, for example). You should use as few control variables as you can get away with.

Matthew also points out that the effect size was small. Well, yes and no. Putting all the variables together could explain just under 20% of the variation between the kids in how many stickers they donated. Actually, I think that’s pretty good – certainly compared with a lot of other studies.

More importantly, the effect of religion was nearly as large as maternal education in predicting altruism. That’s the key comparison – if you believe that socio-economic status is important, then you’d be hard-pushed to dismiss religion as a factor.

But there’s still a problem, Houston.

So the study is sound. It really is the case that, for whatever reason, kids in this study with atheist parents are more generous with their stickers than religious kids.

But unfortunately that doesn’t tell us much.

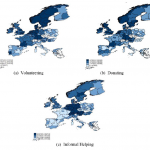

You see, if there’s one thing that regular readers of this blog will know it’s that the characteristics of religious people vary a lot from one place to another. That’s because religion plays different social roles in different societies.

For example, in Jordan there are hardly any atheists. Any atheists in Jordan would have to be really very unusual people. In China, on the other hand, just about everyone is nominally atheist.

The researchers use statistics to control for the average differences between countries in altruism, but that assumes the effect of religion and atheism are the same in each country. They don’t control for the differences between religious and atheists kids in each country, and in fact, it’s hard to see how they could. It’s another example of the limitations of statistics in correcting for fundamental problems in your study set up.

The simple way to check whether there is an issue here would be to look at the results for each country individually. Not only would it be fascinating to see, but it would help us to understand what’s driving the results here.

Unfortunately, and remarkably, this key analysis is not provided in the study or in the supplemental material. I’ve asked Jean Decety, the lead author, if he can provide them. If I hear back, I’ll write it up here.

Until then, I’m sadly going to have to accept that this study really doesn’t tell us very much!

![]() Decety, J., Cowell, J., Lee, K., Mahasneh, R., Malcolm-Smith, S., Selcuk, B., & Zhou, X. (2015). The Negative Association between Religiousness and Children’s Altruism across the World Current Biology DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.056

Decety, J., Cowell, J., Lee, K., Mahasneh, R., Malcolm-Smith, S., Selcuk, B., & Zhou, X. (2015). The Negative Association between Religiousness and Children’s Altruism across the World Current Biology DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.056