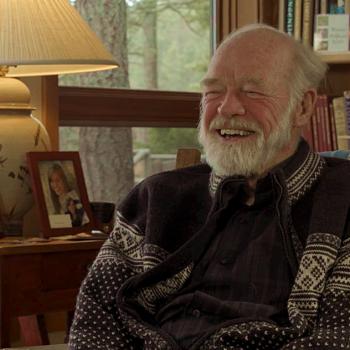

Watching the Winter Olympics from South Korea brought to mind someone I met at a book exposition several decades ago. Jim Willems owned a bookstore in California, and when he learned of my interest in writing he told me a story from his earlier days as a teacher.

“We teachers were always looking for kids who need a little extra attention,” he began, “and one gangly, freckle-faced girl caught my eye. I had sixth grade that year, and this shy girl named Peggy always sat on the back row. Often I caught her nodding off, or even openly napping, with her head resting on the desk. So I stopped her one day after class and asked why she always seemed so tired. She explained that she got up at four a.m. each day to practice figure skating at a rink more than an hour away.”

Jim admired the grit of a twelve year old with that kind of discipline. His own father, a missionary to China, had died of cancer before Jim’s tenth birthday, and only the care and generosity of an uncle made it possible for Jim’s family of nine children to stay together. Now he saw a chance to return the favor for a needy student. After agreeing to tutor Peggy after school, he adjusted her homework assignments around her trips to tournaments. In the process he befriended her parents, who were sacrificing to keep their daughter in what was known as “a rich man’s sport.”

When Peggy graduated to the junior high school across the street, Jim argued her case before skeptical teachers, who saw skating as a distraction from Peggy’s studies. “I know ice skating seems odd in southern California,” he said, “but this girl shows promise, and she works harder than any student I’ve had. With that persistence, she can go places someday.” In the end they, too, agreed to adapt schoolwork to her grueling schedule.

That year, 1961, a plane carrying the US figure skating team crashed in Belgium en route to the World Championships, killing all eighteen skaters along with their coaches and families. Peggy lost her skating heroes and role models, as well as her personal coach.

When he heard the news, Jim crossed the street to the junior high school. “I found her alone, head down, sitting at a table in the far corner of the cafeteria. She was devastated. I groped for words that could keep her from giving up the sport entirely. I told her the mantle of US skating had fallen, and she was one of the few who could pick it up. And almost as an afterthought, I added, ‘Peggy, when you win a gold medal at the Olympics, I’ll be there to see you.’”

“Thanks,” Peggy said, forcing a smile through her tears. “I’ll remember that.”

From that day forward Peggy had one goal: to win Olympic gold. She spent six to eight hours a day on ice, leaping, spinning, and perfecting the delicate choreography of every move. Off the rink she felt like an awkward adolescent. Perched on thin skate blades, she was a ballerina, poetry in motion. At a time when figure skaters emphasized flamboyance and athleticism, she preferred a fluid, classical style.

At the age of 15 she placed sixth at the Innsbruck Olympics and from there went on a tour of Russia to great applause. Once more, disaster struck. Back in California, her father, 41, died of a heart attack. In the midst of her grief, she wondered if her skating days had ended. Her mother would need to get a job to pay the bills. And each week mother and daughter drove in a beat-up compact car 425 miles to San Francisco for skating lessons. How could they keep up such a schedule?

Again, Jim Willems stepped in. He helped with the driving for a time, sitting rinkside for hours with a book to read as the plucky teenager went through her routines. Finally, he arranged a skating scholarship and a move to Colorado’s exclusive Broadmoor Club, which allowed Peggy to juggle time between the classroom and the rink. There she began working with the renowned coach Carlo Fassi.

In 1966, 16-year-old Peggy won the first of three consecutive world championships, reviving the spirit of an Olympic team that had been crushed by the loss of its best skaters. At the 1968 Winter Olympics, in Grenoble, France, she felt the weight of a nation’s expectations. Deeply divided by the Vietnam war, Americans were looking to the games as a hopeful diversion.

The finals of ladies’ figure skating came toward the end of the games, and the US had not won a single gold medal. Peggy was our last chance.

True to his promise, Jim Willems had made the trip and sat in the stands, waiting for his former student’s performance. He remembers, “Here was this 109-pound young woman in a chartreuse outfit, with five minutes to impress judges who all too often let their politics sway their scoring. Would they stonewall us with Cold War bias?

“I reached over for my wife’s hand and whispered that I hoped Peggy would go conservative, not risking a fall. The first notes of Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony sounded, and right away I saw that she was going for broke. She used every foot of ice in the rink, bringing the crowd to their feet with her axels and toe loops. I could hardly hear the music she was skating to, for all the shouts and applause.”

Every judge but one ranked Peggy Fleming first, earning her the gold medal. For the first and only time in those Olympic games, the band played “The Star Spangled Banner.” And a sixth-grade teacher went home convinced he had made a good investment.

Eventually Sports Illustrated would name Peggy, along with Jackie Robinson, Billie Jean King, Richard Petty, Pelé, Bill Russell, and Arnold Palmer, as one of seven athletes who forever changed their sport.

Philip Yancey is an award-winning Christian author, whose books include Disappointment with God, Where is God When it Hurts?, The Jesus I Never Knew, What’s So Amazing About Grace?, and Prayer: Does It Make Any Difference?