In Catholic spirituality silence is associated with humility and reverence. Silence is the abyss in which we encounter God; it is a form of poverty, in which we cede the right to be heard; it is a refuge from the clamor of media/entertainment/Twitter/”the take economy.” It is properly opposed not to singing but to noise. (EE Cummings wrote, “(silence is the blood whose flesh/is singing).”) This is the perspective of Robert Cardinal Sarah’s 2016 The Power of Silence.

In gay communities and gay culture silence is associated with repression, oppression, lies, and self-destruction. The central image of silence for us is the poster from the height of the AIDS epidemic in the US, the pink triangle with SILENCE = DEATH above it. The activity which brings us into a gay community and in a sense constitutes our communities is the act of coming out: breaking silence, speaking.

Can these perspectives be reconciled? It seems to me that they can even reinforce one another.

Coming out is often an act of profound humility. Not for me really, because I was raised in a progressive environment. But for so many gay Christians, coming out is an admission: less an assertion than a response. It is an act of acceptance. You finally give up your strenuous efforts at conformity, normalcy, all the busy fictions you’ve been trying to make real. You give up your idea of what God is supposed to do for you.

And in this admission you learn what He actually has done for you. You enter into a life which is so much more honest and trusting–with oneself, with others, with God–than the life you knew. You free yourself from the multiplicity of lies and enter the simplicity of truth: the truth not primarily about your sexual desires or their persistence, but about God’s enduring love for you and for the other gay people you now begin to meet. You lose your expectations of what a Christian is supposed to be. You lose your unfounded confidence in your own strength and determination. You set aside all those colorful, fake imagined futures in which you fit in because you’ve become somebody else. You begin to try to love gay people as God loves us. You begin to practice abandonment.

The silence which equals death is full of noisy lies. The closet isn’t privacy. Privacy is prepared to give an honest accounting if necessary. Sometimes the closet is armor; sometimes you’re terrified and for good reason. Sometimes the closet is a long passage with several doors branching off it, and you’re unsure which one to walk through. In these circumstances it’s nobody’s place to tell you what to do. But the problem with the silence of the closet is that it breeds so many words, spoken and unspoken: the homophobic joke you tell for camouflage, the nervous laugh, the pronoun games, the fake camaraderie, the self-condemnations, the repeated desperate prayers and the rage at oneself, at God, at the Church, when these begging demands aren’t met.

There is a death in coming out as well. It is the death of the person other people thought you were. It’s often the death of the person they wanted you to be. It might be the death of the person you wanted to be. You lie in the closet with that persona wound all around you, covering your mouth, binding your hands, covering your face; when Jesus, our Truth, calls you to come into the light, you come out, and He says, Take off these burial coverings.

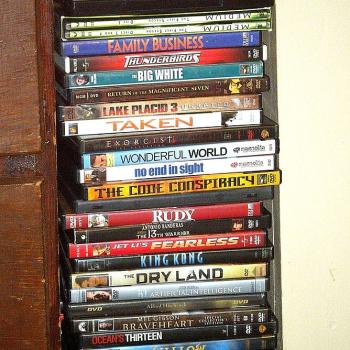

This is what Catholic theologians of silence can learn from gay people. What we can learn from the theologians of silence is also relevant. A lot of people, having come out, emerge from this self-confrontation into a clamor of identities and personae. We put buttons on our clothes. (There was a great ironic one that said, NOBODY KNOWS I’M A LESBIAN–I think I had the far less-ironic version, EVERYBODY KNOWS I’M A LESBIAN.) We talk about gay cartoon rat weddings and immerse ourselves in a sea of queer culture which is simultaneously relief and distraction. All of this is part of a normal journey–it’s basically convert enthusiasm, with all the sweetness and immaturity new converts manifest. Sorry, I don’t even mean to sound so judgmental here, I also watch a lot of gay movies (although I lack a taste for the wholesome). I don’t think caring about queer culture is simply a phase you pass through. But there’s often a specific phase we’ve all seen, which we might call the noisy phase or clamor phase, where the release of being finally a gay Christian and not a closeted Christian kind of overwhelms your intimate relationship with Christ. This sometimes manifests as seeking the exact right identity or subculture: Am I a demisexual panromantic? (Girl, you are a lesbian who has a dude best friend. Pull it together.) Am I a soft butch? Am I a lesbro?

Remembering that silence is intimacy with Christ can keep all that stuff in its place. [ETA: The same is true for my own busy, wordy self-defenses, all these apologias I produce pro vita sapphica. I once read a draft essay critiquing my theology on gay stuff and I wrote a literally seven-page email in response. Never write seven-page self-defense emails.]

All words are insufficient. All identities fail to express the image of God we bear. That doesn’t make your words lies–I can honestly say “I’m a Christian” even though my true identity is as a beloved daughter of God. But it does mean that your words should point you to a place where words cease.

Let your speech be witness, standing with the despised and targeted. And let your honest speech protect your prayer, whose flesh is silence. Speak the truths that help create for you that quiet refuge in your soul, that hushed bridal chamber where you can be together with the One Who knows you before you speak.

This post was inspired by Grant Hartley’s workshop on “Queer Treasure” (an earlier version is here) and Mrs. Renee Higgins’s prayer and preaching on the raising of Lazarus, both at Revoice 2k19. Picture of the Raising of Lazarus is by Duccio di Buoninsegna and via Wikimedia Commons.