Memento is a gimmicky movie, but in the best possible sense of the word.

Memento is a gimmicky movie, but in the best possible sense of the word.

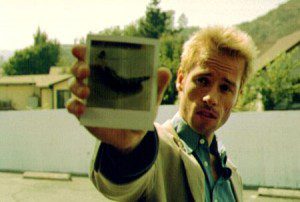

The film begins with a shot of a hand holding a Polaroid; in the picture, and behind it, we see what looks like a dead body, lying against a blood-splattered wall. Then the hand shakes the picture, and we realize the image is fading to white — time is going backwards. Then, sure enough, the blank Polaroid is sucked back into a camera, the blood runs back towards the body from which it came, a gun jumps off the ground into the photographer’s hand, and the body springs to life, the victim having just enough time to shout something before the scene comes to an abrupt end.

These are the only reverse-motion images in the entire film, but they prepare us for what comes. Memento, like many a film noir, begins at the end, with someone’s death. But unlike most other films in this genre, which jump right back to the beginning and then follow a more or less straight line back to the death scene that started the film, Memento — which revolves around a man named Leonard Shelby (Guy Pearce), who suffers from short-term memory loss — hops backwards one scene at a time, until it ends at the beginning. As each scene begins, Leonard has no idea what has happened to him earlier in the story, and neither do we. It’s like watching a DVD with the chapters programmed in reverse.

It is Leonard who holds the gun and takes the picture in the film’s opening scene, and he kills the man at his feet because he is convinced that this is the man who murdered his wife some time ago. Leonard’s memory problems are the direct result of a head injury he sustained while trying in vain to defend his wife; ever since that incident, he has been looking for revenge, and he obsessively surrounds himself with photos, notes and clues — some of which are tattooed to his body — to help him find the killer.

Despite his perpetual memory loss, Leonard is very confident in his ability to track the killer down this way; if you surround yourself with facts, he says, then memories, which are notoriously prone to change anyway, don’t matter. But as the story unfolds, we see that there have been times in Leonard’s search when his instincts have told him he is being manipulated into killing the wrong person. And hanging over Leonard’s efforts is the question of whether there is any point to revenge anyway, if he will forget that he got it in the end. Time cannot heal Leonard’s wounds, because for him there is no past or future, only an eternal “now” that is filled with anger and guilt.

Pearce brings the same agile intelligence to this role that he brought to his virtuous but scheming cop in L.A. Confidential, but this time, there is an extra hint of melancholy. The supporting cast includes two actors with ties to Vancouver: The Matrix‘s Carrie-Anne Moss plays a bartender who helps Leonard in return for a favour, and Due South‘s Callum Keith Rennie appears briefly as a drug dealer who has an axe to grind with Leonard, for reasons Leonard no longer knows. But if any actor steals the show, it is Joe Pantoliano (also of The Matrix), whose shady character may or may not be the killer that Leonard has been looking for. Pantoliano gets some of the film’s funnier lines; at one point, he sighs, “I’ve had more rewarding friendships, although I do get to tell the same jokes.”

Director Christopher Nolan adapted the film from a short story written by his brother Jonathan, and it’s an exciting brain-teaser on several levels. First, there is the plot, which is convoluted enough to keep you and your friends hashing out the story for hours after the film is over; I haven’t wanted to puzzle over a film’s plot twists with this much enthusiasm since The Sixth Sense and, before that, The Usual Suspects. Second, there is the deeper issue of how memory, identity, and responsibility intertwine. Third, there is the broader question of whether our actions have any absolute meaning beyond what we give them. Do Leonard’s actions have meaning once he forgets them, and if so, what is it?

In his Confessions, Saint Augustine called memory “the belly of the mind”; it is the place where all of our experiences are stored and digested, long after we have ceased to have the experiences themselves. Without memory, we cannot learn new things, nor can we grow in our relationships with God or our fellow humans. Without memory holding his experiences together, there would not be a single Augustine, who left the hedonism of his youth to devote himself to God, but many Augustines, each one living in the moment without any connection to his past or future. Similarly, in ‘Memento Mori‘, the short story which inspired this film, the narrator asserts that “every man is a mob, a chain gang of idiots,” and that life is “a daily pantomime, one man yielding control to the next.”

The fact that human memory is so prone to error just accentuates these problems, and the theological ramifications are significant. In her thoughtful book Living the Questions, Carolyn Arends describes her grandfather’s bout with Alzheimer’s disease, and asks, “How do we partake in the story of redemption if we are at risk of having our own stories snatched from us?” For Augustine, the only solution was to appeal to the transcendent God, who alone has a perfect view of reality, and can thus keep us whole. But for Leonard Shelby, there can be no redemption, and no healing, at least not in this life.

Memento is a cautionary tale about the futility of revenge and the dangers of the scapegoat mechanism. It is also a powerful reminder that no one person can create meaning on his or her own.

Internet Movie Database | Movie Review Query Engine

USA: R | BC: 14A | ON: AA

— Versions of this review were first published in the Vancouver Courier and on the website for BC Christian News.