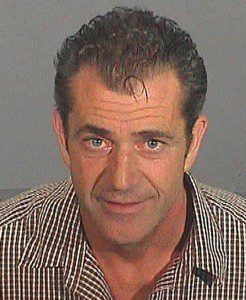

YOU MAY have heard about a little incident involving Mel Gibson, a speeding car, an open bottle of booze, and some racist and sexist remarks in late July.

YOU MAY have heard about a little incident involving Mel Gibson, a speeding car, an open bottle of booze, and some racist and sexist remarks in late July.

For some people, the incident proved what many had been saying for at least three years, namely that Gibson is an anti-Semite, and that the controversial movie he made about the death of Jesus, The Passion of the Christ, is anti-Semitic.

But is it as simple as that? There are several issues tangled up in this story, and each one needs to be addressed separately.

First, it is dangerous to define a person by the sins with which they struggle.

Before Gibson released the second of his two apologies — in which he specifically appealed to the Jewish community for help in finding “the appropriate path for healing” — Abraham H. Foxman of the Anti-Defamation League released a statement saying that Gibson had revealed “his true self” through his drunken behaviour.

There is admittedly some truth to the old saying, in vino, veritas (“in wine, there is truth”). People are indeed more likely to express the emotions churning within them when they consume substances that hinder their better judgment. But are these emotions necessarily more “true” than the self-control that keeps them in check?

As Paul says in Galatians, there is a conflict between the “spirit” and the “flesh” in all of us, which is precisely why we are supposed to practice self-control — one of the “fruits of the Spirit” — and not the path of drunkenness and fits of rage.

Self-control is one of the ways in which we make ourselves more like the people that God wants us to be; indeed, it is one of the ways in which we become our “true selves”. This sick, sinful, corrupted flesh is only a shadow of the “true self” that each of us is struggling to become — on our better days, at least.

It is kind of like the relationship between bravery and fear. We would not need bravery if we felt no fear; to be brave is to control our fear. But would anyone argue that a person’s fear somehow reflects his “true self”, more than his bravery?

So it may be that Gibson’s fit of drunken rage revealed one aspect of his “true self” — an aspect that can be traced back to the influence of his Holocaust-denying father. But it is also possible, and perhaps even more accurate, to say that his drunkenness damaged a part of his “true self” that would have held those passions back.

Second, an artist is not his work of art, and a filmmaker is not his film.

Rob Reiner, director of Stand By Me and When Harry Met Sally…, told the Associated Press last Friday that Gibson must not only apologize for the remarks he made to the police, but must also acknowledge that “his work reflects anti-Semitism.”

Referring specifically to The Passion of the Christ, Reiner said: “When he can come out and say, you know, ‘My views have been reflected in my work and I feel bad that I’ve done that,’ then that will be the beginning of some reconciliation for him.”

Reiner might want to tread carefully here, since a number of his own films contain traces of anti-Christian prejudice. But there are other reasons to resist this line of thought, not least that it is overly simplistic. The Passion is more complex than that.

Even if Mel Gibson were an anti-Semite, it would not necessarily follow that his film is anti-Semitic. But the reverse is true, too: Just because Gibson is not an anti-Semite, it does not necessarily follow that his film is free of anti-Semitic elements.

So in one sense, the things Gibson said when he was arrested for drunk driving make no difference to how we ought to interpret The Passion. The film remains what it is, and it still deserves to be interpreted on its own terms. What happens within the frame is a heck of a lot more important than what happens in the tabloids.

That said, I do find that at least one of Gibson’s alleged remarks (“The Jews are responsible for all the wars in the world”) casts a sinister light on one aspect of the film. It calls to mind the unfortunate scene in The Passion where a pensive Pontius Pilate frets that Caiaphas, of all people, might lead a rebellion against him.

That scene is completely bogus, both historically and biblically. The Bible portrays Pilate as a brutal, cynical tyrant and Caiaphas as a leader who is all too willing to kill one man to keep the peace; but Gibson’s film reverses these character traits.

However, it is worth noting that this and other allegedy anti-Semitic elements in The Passion derive not from Gibson himself but from Gibson’s source materials — including the medieval passion plays, which were historically associated with flare-ups of anti-Semitic violence, and the visions of Sr. Anne Catherine Emmerich, which inspired much of the brutality in the film that is not found in the Bible.

And it is worth noting that Gibson himself put in quite a few pro-Semitic elements that appear to have been original to him. Note especially how he underscores the Jewishness of Simon of Cyrene, easily one of the film’s most appealing characters, or the way the Virgin Mary quotes a key line from the Passover seder.

So The Passion of the Christ is a mixed bag, just as Mel Gibson himself is a mixed bag; and the film needs to be seen with a critical eye, instead of being reduced to an evangelistic tool or an excuse for Christians to prove their box-office clout.

To the extent that Christians were already evaluating the film from a critical point of view, noting its various strengths and weaknesses, the arrest of Mel Gibson won’t make much difference. But to the extent that Christians used the film as a political football or a flag to rally around, this recent incident may serve as a warning.

As for Gibson himself, he could probably use our prayers; it can’t be easy to deal with a bigoted father, a history of addiction and depression, and the intense scrutiny of the world at large. The Passion of the Christ was the profoundly personal work of a man who has been to dark places and is struggling to work out his salvation in fear and trembling; and alas, that struggle continues even when the credits roll.

— A version of this article was first published in BC Christian News.