The Bible epic, as a genre, is typically associated with the 1950s, and for good reason. That’s when Hollywood churned out a series of Bible-themed films, such as David and Bathsheba (1951), The Robe (1953) and The Ten Commandments (1956); and both the decade and the genre reached their climax with Ben-Hur (1959), which won a record number of Oscars in addition to becoming one of the biggest box-office hits of all time.

The Bible epic, as a genre, is typically associated with the 1950s, and for good reason. That’s when Hollywood churned out a series of Bible-themed films, such as David and Bathsheba (1951), The Robe (1953) and The Ten Commandments (1956); and both the decade and the genre reached their climax with Ben-Hur (1959), which won a record number of Oscars in addition to becoming one of the biggest box-office hits of all time.

But the decade arguably got its start in the 1940s, when Cecil B. DeMille produced Samson and Delilah (1949), starring Victor Mature and Hedy Lamarr. It was the first major Bible movie made by an American studio since the silent era — or since the early sound era, if we count DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross (1932), which takes place after the Book of Acts, as a “Bible movie” — and it was a fairly big hit, thereby paving the way for all the bathrobe epics that followed.

Despite the film’s historical significance, and despite its pedigree — in addition to Mature and Lamarr, it also featured George Sanders and Angela Lansbury, the latter of whom was only 24 when the film came out — the film had somehow never received an official DVD release, at least not in North America, until a couple months ago. And, remarkably, although the film received a fairly lavish digital restoration prior to its DVD release, the studio has so far declined to release it on Blu-Ray.

Ah well. No matter. The DVD is out now, and that gave me an excuse to watch it recently — for the first time in years — and take a few notes. Here’s what I noticed.

How it fits with DeMille’s other films. First, I cannot help but look at this film in the light of DeMille’s later, and much more famous, remake of The Ten Commandments. The later film is clearly superior to this one, partly because it had a much bigger budget and better production values, but also because it strikes just the right balance between tongue-in-cheek campiness and earnest sincerity.

How it fits with DeMille’s other films. First, I cannot help but look at this film in the light of DeMille’s later, and much more famous, remake of The Ten Commandments. The later film is clearly superior to this one, partly because it had a much bigger budget and better production values, but also because it strikes just the right balance between tongue-in-cheek campiness and earnest sincerity.

There is nothing in Samson and Delilah that can compare to Sir Cedric Hardwicke’s heartbreak when he allows his prejudice to overwhelm his love for Moses, and even Anne Baxter’s vamping in the later film is fuelled by a bitterness that is far more convincing than anything Hedy Lamarr summons in the earlier film. George Sanders, as the leader of the Philistines, is his usual dry, cynical self, and amusing enough as far as that goes, but I don’t find his performance anywhere near as compelling as the strutting ego that Yul Brynner brings to his Pharaoh in the later film.

Even when both films introduce a plain but “good” woman to counterbalance the opulence and seductiveness of the leading lady, the later film’s Yvonne DeCarlo seems to possess an inner strength that is appealing in its own right, whereas the Olive Deering character in Samson and Delilah is so mild-mannered she practically deserves the dismissive taunts thrown her way by Delilah. (Deering’s character, incidentally, is named Miriam — and Deering would go on to play Moses’ sister Miriam in The Ten Commandments.)

Meanwhile, the screenplay for Samson and Delilah is teeming with cheesy dialogue, much of which consists of animal metaphors for humans and their behaviour. (My favorite bit, by far, is the one where Delilah runs to Samson after he kills the lion, and Samson replies, “Hey, one cat at a time!”) The Ten Commandments had its share of that, too, of course, but it had other qualities that compensated for the cheesiness — and, like I say, it had actors who were capable of elevating the material, such as it was.

Meanwhile, the screenplay for Samson and Delilah is teeming with cheesy dialogue, much of which consists of animal metaphors for humans and their behaviour. (My favorite bit, by far, is the one where Delilah runs to Samson after he kills the lion, and Samson replies, “Hey, one cat at a time!”) The Ten Commandments had its share of that, too, of course, but it had other qualities that compensated for the cheesiness — and, like I say, it had actors who were capable of elevating the material, such as it was.

I am also struck by how the visual and theatrical style of the film is quite similar to that of DeMille’s silent films, even though it was produced over 20 years after the end of the silent era. The staginess of certain scenes — such as the one where the Philistines are about to put out Samson’s eyes, but they pause for about a minute so that he can speak a few lines — strikes me as the sort of thing that happened quite often in films of the 1920s, but would certainly not be accepted as dramatically plausible today. I wonder to what degree audiences of the 1940s still accepted these sorts of conventions, and to what degree things like this might have already seemed kind of archaic to them.

Biblical source material. I noted the other day that Samson and Delilah might be the only major-studio Bible movie that actually spells out which chapters of the Bible it is based on in its opening credits. But the film uses both less and more of the Bible than it indicates.

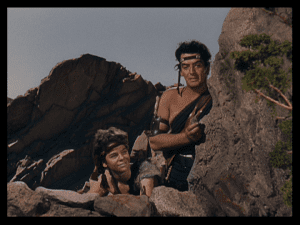

Ironically, the film says it is based on four chapters in the Book of Judges, namely chapters 13 to 16 — but then it doesn’t even use chapter 13, which is the chapter that describes Samson’s birth. Instead, the film begins when Samson is already an adult — and it gives him a young sidekick named Saul, the future first king of Israel, who is never mentioned in Judges but is mentioned in I Samuel and I Chronicles. (The biblical Saul came from the tribe of Benjamin — a not-insignificant detail — but the film seems to identify him with the tribe of Dan, which is where Samson came from.)

Ironically, the film says it is based on four chapters in the Book of Judges, namely chapters 13 to 16 — but then it doesn’t even use chapter 13, which is the chapter that describes Samson’s birth. Instead, the film begins when Samson is already an adult — and it gives him a young sidekick named Saul, the future first king of Israel, who is never mentioned in Judges but is mentioned in I Samuel and I Chronicles. (The biblical Saul came from the tribe of Benjamin — a not-insignificant detail — but the film seems to identify him with the tribe of Dan, which is where Samson came from.)

The film then gives Saul characteristics that we associate with the young David, such as a slingshot that he wears around his head. Later, when Samson is languishing in a Philistine prison, he can be heard saying a prayer that sounds remarkably similar to Psalm 22, which is the “psalm of David” that Jesus quoted when he was on the cross. And the dialogue throughout the film contains scattered references to Nimrod, Jael and Moses, all of whom lived before Samson’s time and are described in earlier parts of the Bible.

(Saul, incidentally, is played by 14-year-old Russ Tamblyn, who went on to co-star in films like Father of the Bride (1950), Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (1954) and West Side Story (1961); in more recent years, he has had supporting roles in TV shows like Twin Peaks (1990-1991) and Joan of Arcadia (2004), and he even had a small part in Django Unchained (2012).)

A more heroic Samson. The biblical Samson is something of a perpetual screw-up, who falls for the wrong women and squanders his divine gifts on petty revenge but never quite tackles the Philistines the way he is supposed to. When the narrator of Judges tells us that Samson killed more people in his final, suicidal act than in all his previous acts combined, the note struck there is arguably less one of triumph than one of regret that Samson had not done more.

The film cannot avoid the broad contours of Samson’s story, of course, but it does tweak things in ways that make Samson look a little more heroic.

The opening narration tells us that Samson embodied the eternal “unquenchable thirst for freedom” and that he dreamed of “liberty for his nation.” The character in the film prays more often than the character in the Bible. Some of his mighty deeds are amplified by miraculous effects that have no precedent in the Bible, such as the thunder and lightning that accompany him as he kills the Philistine soldiers with a donkey’s jawbone.

Some of his more callous acts, such as tying torches to foxes’ tails and letting them run wild through the Philistine fields, are written out of the film. Others are toned down, so that, for example, instead of killing thirty Philistines for their clothes, he now merely robs them of their clothes, in a sequence that is played for laughs. (His first victim is played, believe it or not, by Arthur Q. Bryan, the voice of Elmer Fudd.)

Some of his more callous acts, such as tying torches to foxes’ tails and letting them run wild through the Philistine fields, are written out of the film. Others are toned down, so that, for example, instead of killing thirty Philistines for their clothes, he now merely robs them of their clothes, in a sequence that is played for laughs. (His first victim is played, believe it or not, by Arthur Q. Bryan, the voice of Elmer Fudd.)

In addition, Delilah’s first three attempts to learn the secret of his strength — attempts that, in the Bible, were followed by Delilah binding Samson in his sleep and waking him with men in the room, ready to capture Samson — are virtually eliminated from the film, thus minimizing the extent to which Samson exposes his foolishness by finally telling her the truth.

And finally, the film generates sympathy for Samson by criticizing both the Israelites and the Philistines for their treatment of him. When the Israelites agree to turn Samson over to the Philistines, roughly halfway through the film, an older Israelite says, “Why will men always betray the strongest among them?” And when the blind, defeated Samson is paraded before the Philistines at the very end of the film, and Delilah says the people are behaving like devils, the George Sanders character replies, “No, they’re very human. The weak always band together to pull down the strong.”

So, basically, it’s the fault of the masses that Samson was brought down in the end. Which is an odd sentiment to express in a film aimed at the masses.

Less whores, more Delilah. In keeping with the overall attempt to make Samson look better on film than he does in the Bible, the film also eliminates the bit about Samson visiting a prostitute in Gaza — though it does give Delilah a bit of dialogue later, in which she alludes to how Samson carried the city’s gates away. (The Philistines had locked the gates while Samson was in the prostitute’s house, hoping to trap him there.)

Less whores, more Delilah. In keeping with the overall attempt to make Samson look better on film than he does in the Bible, the film also eliminates the bit about Samson visiting a prostitute in Gaza — though it does give Delilah a bit of dialogue later, in which she alludes to how Samson carried the city’s gates away. (The Philistines had locked the gates while Samson was in the prostitute’s house, hoping to trap him there.)

In fact, where the Bible gives us the impression that Samson had a thing for the ladies — and that his thing for the ladies was constantly getting him in trouble — the film reduces his romantic entanglements to two, and it links these two by making Samson’s wife the sister of Delilah. What is more, the film amplifies Delilah’s role in the story so that everything revolves around her; she is, indeed, its central protagonist. Just as it was Nefertiri who hardened Pharaoh’s heart in The Ten Commandments, it is Delilah who manipulates all the other characters in this film and makes them do what they do.

It is Delilah who tells the Saran (the Philistine leader played by George Sanders) that thirty Philistine men should attend Samson’s wedding to her sister Semadar (the Angela Lansbury character). It is Delilah who persuades those men to pressure Semadar into learning the secret of Samson’s riddle. When Samson storms off, it is Delilah who proposes that Semadar be given in marriage to one of the Philistine men.

Then, some time later, when Delilah strikes a deal with the Philistine leaders to help them get rid of Samson in exchange for thousands of shekels, it is she, not they, who proposes the idea and sets the price — and she then goes on to seduce Samson with the explicit intent of betraying him, whereas in the Bible, she is already romantically involved with Samson when the leaders bribe her into betraying him.

Finally, it is Delilah who leads Samson to the pillars of the Philistine temple, thus enabling his final, suicidal act. And when Samson calls out her name to confirm that she has retreated to a safe distance, it is she who stays silent so that she can witness the destruction of the temple, at the cost of her own life.

There is also a striking moment, about half-way through the film, in which Delilah swears vengeance against Samson after her family’s home burns to the ground, taking her family with it, and I could not help but think that the imagery was reminiscent of that famous scene from Gone with the Wind (1939) where Scarlett O’Hara witnesses the devastation of her father’s plantation and swears that she’ll never go hungry again, even if she has to “lie, steal, cheat or kill.”

Cartoonish connections. I’ve already mentioned that the voice of Elmer Fudd plays one of Samson’s victims.

Cartoonish connections. I’ve already mentioned that the voice of Elmer Fudd plays one of Samson’s victims.

Interestingly, another of his victims — a Philistine soldier who barely survives the jawbone incident — is played by George Reeves, who was just two years away from starring in Superman and the Mole-Men (1951) and the TV series that followed. (That’s more of a comic-book connection than a cartoon connection, per se, but you get the idea.)

I cannot help but also think that the father of Delilah and Semadar comes across as one of those really buffoonish dads that you often see in Disney cartoons, going back at least as far as Cinderella (1950).

Gender relations. Oh, the sexism. Not only is everything the fault of the scheming, sexual manipulator Delilah, but the film makes several references to marriage — and to wives in particular — that would make modern audiences roll their eyes or worse.

To cite the first three that come to my mind: There is the Philistine whose robe is stolen by Samson, and who then tells the authorities that his wife made that robe for him and will “never believe” that it was stolen. Then there is the woman in the Philistine temple who asks her husband why he doesn’t follow her the way men follow Delilah. And finally, there is the bit where Semadar tries to get the answer to Samson’s riddle and says, weeping, “Our wedding night, and to you I am no one!” — and all Victor Mature’s Samson can do is sigh and say, “Women.”

All that being said, there is an interesting exchange between Delilah and Miriam, in which Delilah claims the right to love Samson because she treats him “as a man of flesh and blood” and not just as a living myth, the way the Israelites do. Ordinarily, you would expect a film like this to privilege spiritual things above the physical — but given how utterly fallible Samson is, you cannot help but think that Delilah’s argument has some merit.

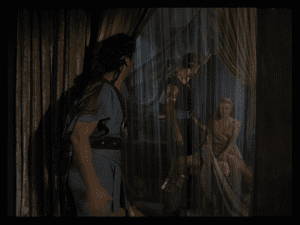

Sexiness of gauze. Early in the film, one of the Philistine generals handles some new fabric from Gaza and says, “They call it gauze.” Apparently the fabric really does take its name from that city, but the earliest historical references to it date from the 13th century AD — thousands of years after the story of Samson takes place.

Sexiness of gauze. Early in the film, one of the Philistine generals handles some new fabric from Gaza and says, “They call it gauze.” Apparently the fabric really does take its name from that city, but the earliest historical references to it date from the 13th century AD — thousands of years after the story of Samson takes place.

No matter, though. The point here is that DeMille gets a significant sexual charge out of the stuff, in two key scenes in particular.

First, there is the scene where Samson pulls a curtain aside and exposes Semadar with her new husband, and while there’s nothing here that would raise the ire of a 1940s movie censor, you can still feel the sexual betrayal on Samson’s part, and the invasion of privacy on Semadar’s.

And then there is the scene in which Delilah lowers the curtain around her bed before cutting Samson’s hair, thus accentuating the intimacy of her betrayal.

Conscious of posterity. The characters in this film are very aware of themselves as people who are part of a story in the making. When the Israelites prepare to turn Samson over to the Philistines, one of them declares, apropos of nothing in particular: “His name will be written in the Book of Judges.” And when Samson commits his final, suicidal act, Miriam tells Saul, “He did not die, Saul. Men will tell his story for a thousand years.”

Delilah is also informed that her name will live in infamy. When Samson realizes that she has betrayed him, he declares, “The name Delilah will be an everlasting curse on the lips of men.”

In a more amusing vein, when the Saran complains at length to his fellow Philistine nobles that they have been humiliated by Samson and his donkey’s jawbone, he turns at one point to one of his scribes and says, “Don’t set that down, you fool!”

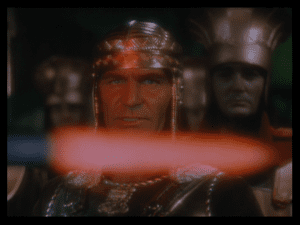

Camera angles! DeMille may have begun his career on the stage — and his films may reflect the pompous theatricality of his stage productions — but he certainly knew how to use a camera at times. Two shots in particular stand out, for me, though there are probably others that one could point to, as well.

Camera angles! DeMille may have begun his career on the stage — and his films may reflect the pompous theatricality of his stage productions — but he certainly knew how to use a camera at times. Two shots in particular stand out, for me, though there are probably others that one could point to, as well.

First, the point-of-view shot as the Philistines prepare to put out Samson’s eyes with a super-hot blade. It’s not just that the blade comes super-close to the camera; there are also subtle changes in lighting, and a wavy effect that suggests the heat of the blade is distorting the image, that really sell this moment.

Second, the scene where the Saran brings Delilah to the millhouse so that she can see Samson in bondage. As the scene begins, Delilah has no idea that Samson has been blinded, so she decides to strut her stuff in front of him — and the camera, positioned behind Samson’s back as he pushes the stone around the mill, comes closer to Delilah and stays with her in close-up as the horror of what has happened to Samson dawns on her, and Samson walks back out of the frame.

So what starts out as a Samson-point-of-view shot that has been denied to Samson himself — an objectifying shot of Delilah, if you will — turns into a more subjective image in which we share Delilah’s distress at her discovery.

Odds and ends. The production values on this film are impressive in places, and laughably bad in others. Good: the collapse of the Philistine temple. Bad: Samson’s fight with the lion, where the stunt-man shots are inter-cut with close-ups of Victor Mature grunting as he holds a stuffy by the paws. The streaks of blood on Samson’s arm at the end of that sequence, which I think are supposed to represent actual wounds, look rather fake too.

Odds and ends. The production values on this film are impressive in places, and laughably bad in others. Good: the collapse of the Philistine temple. Bad: Samson’s fight with the lion, where the stunt-man shots are inter-cut with close-ups of Victor Mature grunting as he holds a stuffy by the paws. The streaks of blood on Samson’s arm at the end of that sequence, which I think are supposed to represent actual wounds, look rather fake too.

Finally, I was struck by the fact that, when Samson is captured and about to be blinded by the Philistines, he says, in a prayer directed to God, “My eyes did turn away from you . . . Now you take away my sight, so that I may see again more clearly.” This is remarkably similar to the scene in the recent mini-series The Bible where Samson, just before destroying the Philistines, declares, “I can see him [i.e. God] more clearly than ever.” Coincidence, or a conscious borrowing from DeMille’s film?

And that’s about it, for now. Incidentally, while the film was not officially released to DVD until a couple months ago, it has long been available on VHS, and copies of it have been posted to YouTube and the like. You can watch the entire film below:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QLqgrrACUe0