Two movies about Jesus, both of which were quite controversial in their day, are celebrating major anniversaries this month.

Two movies about Jesus, both of which were quite controversial in their day, are celebrating major anniversaries this month.

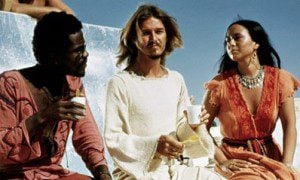

First, there is Jesus Christ Superstar, which premiered in New York City 40 years ago yesterday before going into general release on August 15, 1973.

I don’t appear to have written all that much about this film over the years, though I did write the following about the 25th-anniversary edition of the soundtrack in an article for BC Christian News that was first published in 1999:

Superstar, composed by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, remains a popular show, and with good reason. The tunes are catchy, electrifying, and at times deeply passionate, and the lyrics, which dwell on the vacuity of our modern celebrity culture, are as relevant as ever.

But the story is as consistently cynical and agnostic a deconstruction of the life of Jesus as anyone has ever put on film. Jesus, as presented here, is just an innocent weakling caught, almost off his guard, amid the power games of mindless zealots and ruthless political leaders.

I also devoted a couple paragraphs to the film in my Books & Culture cover story on Jesus films, which I wrote just over a year later:

But if Jesus became a target of social unrest, he was also increasingly portrayed as a political activist in his own right. Norman Jewison’s Jesus Christ Superstar (1973) is particularly interesting in this regard, as it plays both of these angles at the same time. The film, a rock-and-roll musical composed by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, invited the youth of the Woodstock generation to see in Jesus an enemy of the establishment not unlike themselves. But it also takes aim at the belief that Jesus was more than “just a man”; Jesus, in this film, becomes a celebrity who gets swept away by his own fame. The film uses the Jesus story to critique celebrity culture, and vice versa.

Jesus Christ Superstar is also noteworthy for being the first film to inject a clearly postmodern sensibility into its rendition of the Gospels. Pilate not only asks, “What is truth?” He also goes on to say, “We both have truths. / Are mine the same as yours?” For the title song, Judas comes down from heaven and asks Jesus how he would rate himself next to Buddha and Mohammed. The film begins with actors arriving by bus at a desert locale, where they proceed to perform the musical — a play within the play, as it were — and it ends with these same actors getting back on the bus and leaving; even Judas, the one who killed himself, is accounted for. But the actor who played Jesus is nowhere to be seen; he is neither on the cross nor among the cast. Has he transcended the play, somehow?

I referred to the film again a few paragraphs later, in the section on Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979):

Brian’s frustrations, at times, echo those of the biblical Jesus. Jesus provoked his own listeners to think for themselves (Matt. 18:12) and he complained on occasion that his followers’ minds were too dull (Mark 7:18). But where Jesus taught with compassion, Brian is as neurotic as the eccentrics who follow him. In addition, the cult that builds up around Brian has nothing to do with the man himself. Like Jesus Christ Superstar, Life of Brian suggests, albeit indirectly, that the church is founded on a lot of misdirected hype. Although Jesus himself is left untouched, the film raises the possibility that his followers, like Brian’s, got it all wrong.

I also included a paragraph on the film in an essay I wrote for Scandalizing Jesus?: Kazantzakis’s The Last Temptation of Christ Fifty Years on, in which I explored how different films had addressed the sexuality of Jesus and/or his followers:

The first mainstream film to suggest an erotic link between Jesus and Mary Magdalene, however sublimated, was Norman Jewison’s rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar (1973). As in DeMille’s film, Judas is once again a political revolutionary. But this time, instead of keeping a lover on the side, he objects to the way Jesus allows himself to be distracted by Mary’s attentions as she anoints his feet and head. In this as in so many other things, the Jesus of this film is so passive it is difficult to say whether he actually feels anything sexual for Mary or is simply letting her do what she does. For her part, in a song called “I Don’t Know How to Love Him,” Mary observes that although she has had “so many men before in very many ways,” she does not know what to make of her feelings for Jesus. Does she feel a purer kind of sexual attraction? Or is she on the verge of giving up sexuality for some sort of spirituality? Such ambiguities extend even to Jesus’ relationship with Judas, who repeats a key line from Mary’s song shortly before committing suicide. Indeed, some critics have inferred that there may be something more than political zeal behind Judas’s frustrations. Lloyd Baugh notes that Jesus and Judas exchange “intense looks” and are sometimes framed with Mary in a way that suggests “a rather tense menage a trois.”

Incidentally, Jesus Christ Superstar was one of at least three musical adaptations of the gospels that came out in 1973. The others — Johnny Cash’s The Gospel Road and Stephen Schwartz’s Godspell — came out in March of that year, or about a month before Easter, and thus had their 40th anniversaries a few months ago.

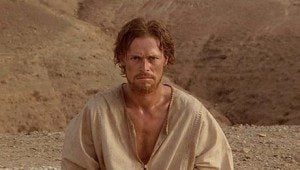

The other controversial Jesus film that is celebrating an anniversary this month is The Last Temptation of Christ, which came out 25 years ago this Monday.

The other controversial Jesus film that is celebrating an anniversary this month is The Last Temptation of Christ, which came out 25 years ago this Monday.

I have written quite a bit about this film over the years, much of it here at this blog or in articles that I have linked to from this blog. So instead of sifting through all that and looking for a few choice paragraphs, I’d like to link to an article by my friend Kenneth R. Morefield that was posted at Christianity Today Movies yesterday:

The Last Temptation marked a tipping point in the American “culture wars.” There had been other films, and have been since, that generated protest, disdain, or both. Michael Haneke’s Amour, for instance, recently drew fire for (its detractors argue) promoting the culture of death. But it also garnered praise outside of religious circles, not to mention a Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

Last Temptation wasn’t simply criticized: it helped establish the battle lines. It is the prime example in the book by Michael Medved that gave this particular battlefield a name: Hollywood vs. America. . . .

Whatever Scorsese’s expectations during filming—it’s worth remembering that at least one studio backed away from even making the film—he reportedly did not attend its premiere. That event, replete with security concerns so new and alien at the time but so depressingly normal today, is another reminder of the ways America has changed in the last quarter century.

But for those, like me, who did not see it when it was originally released, the biggest surprise is how poorly this film has stood the test of time. . . .

Ken’s reference to the “culture wars” reminds me: Darren Middleton, who edited the book on The Last Temptation that I contributed to, also wrote an essay for Re-Viewing The Passion: Mel Gibson’s Film and Its Critics (which I also contributed an essay to) in which he looked at a number of striking parallels between Scorsese’s film and Gibson’s film and the furors surrounding them.

Ken’s reference to “security concerns” also reminds me that I saw Scorsese’s film during its theatrical release, and I can remember how the theatre manager came outside to check our bags before letting us in, to make sure that none of us would be capable of damaging the theatre. That was definitely a first, for me.

Ken also makes a good point about one of the film’s most overtly sexual scenes:

In an early scene, Jesus watches Mary Magdalene have sex (and is then alternately tempted and scorned by her when he rejects her advances). The filmmakers say the scene illustrates humans’ ability to be close to temptation but not sin, but it depicts Jesus as repressed and frightened by Mary’s body, rather than capable of looking past it.

This dovetails with an observation that Lloyd Baugh makes in Imaging the Divine: Jesus and Christ-Figures in Film, where he says that the real problem with Scorsese’s film is not its low Christology but its low anthropology — that is, its low view of human nature, and its suggestion that someone as “repressed and frightened” as Scorsese’s Jesus is somehow representative of humanity as a whole.

These comments also dovetail, to some degree, with my own discussion of that scene in my essay for Scandalizing Jesus?. The passage below comes after a paragraph in which I discuss how careful Scorsese is to hide or obscure male genitalia throughout the film even though naked men are one of its recurring motifs:

There is no such reticence in Scorsese’s depiction of the naked women, though, and in this, he sometimes goes beyond the original novel. This impression is furthered by Scorsese’s use of voyeuristic point-of-view shots. When Jesus first arrives in Magdala, he sees a topless woman sitting by a well, her painted breasts in full view and her eyes ultimately looking straight at the camera, and thus at Jesus and at the viewer. However, in the book this woman is smiling at some merchants, and Jesus reacts to the sight of her so negatively that one can imagine other, less voyeuristic ways that such a shot might have been composed. Jesus then proceeds to the home of Mary Magdalene. In the novel, Mary entertains her clients behind closed doors, one at a time, while the other men wait in an open courtyard, eating and joking about the nature of reality. In Scorsese’s film, however, the men sit inside and watch in silence as Mary takes her partners to bed, and the film cuts from shots of the men’s faces, including the face of Jesus, to close-ups of Mary and her clients in action. Scorsese has said he wanted this scene to dramatize “the closeness, the proximity, of sin, which is around every human being, every day. . . . If [Jesus] could deal with it, we could deal with it.” However, most people are not surrounded by explicit displays of sexual intercourse between strangers every day, and Scorsese’s explanation for this revision tends to confirm Margaret R. Miles’s charge that the film reflects “a modernist reduction of all sin to sins of the flesh.” It is also questionable whether Jesus would have “dealt with” an open display of sin, sexual or otherwise, by becoming one of its spectators.

On a more personal note, The Last Temptation of Christ is also significant to me as it sort of marked the beginning of my life as a published film critic. I wrote the local Christian community paper a letter-to-the-editor about the film and the controversy surrounding it, and within a few months I was writing actual articles for that paper as well. I went on to become one of its regular staffers and I remained their film columnist until the paper was shut down two years ago.

So, that’s another anniversary coming up. How the time flies, eh?

P.S.: Other Bible-movie anniversaries this year include the 90th anniversary of the original version of The Ten Commandments, the 60th anniversary of The Robe and the 10th anniversary of The Gospel of John. Last year also marked the 100th anniversary of From the Manger to the Cross, which was arguably the first feature-length Jesus movie, but I forgot to make note of it at the time. Ah well.