The headlines on some of the early reviews of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire have called it the Empire Strikes Back of this series, and it’s not hard to see why. The new film fleshes out the characters introduced by the first film, it delves deeper into its central love triangle, it raises the stakes significantly, and it ends on an abrupt cliffhanger that separates the characters from one another and leaves you wondering what’s really going on (though the revelation at the end of this film is nothing compared to the famous “I am your father” moment from Empire).

The headlines on some of the early reviews of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire have called it the Empire Strikes Back of this series, and it’s not hard to see why. The new film fleshes out the characters introduced by the first film, it delves deeper into its central love triangle, it raises the stakes significantly, and it ends on an abrupt cliffhanger that separates the characters from one another and leaves you wondering what’s really going on (though the revelation at the end of this film is nothing compared to the famous “I am your father” moment from Empire).

I have never read the original novels, so I have only a vague idea of where the story is going, and no idea at all how faithful the films have been to the books. But I found I cared about this film in a way that I don’t recall caring about the original Hunger Games, which came out a year and a half ago. I was more impressed by how the film looked, and by the complicated interactions between our protagonists, which no longer fit quite so neatly into the familiar formula whereby a hero is called, trained, sent on some sort of quest and then returned to his or her home.

First, the production design. Directed by Francis Lawrence, who takes over from the first film’s Gary Ross, the new film tones down the hand-held shaky-cam look of the original film but keeps the first film’s synthesis of earthy naturalism (in the District 12 scenes, where our heroes work in the mines or go turkey hunting in the woods) and smooth digital gloss (in the Capitol scenes, where the elite of this futuristic, totalitarian society cocoon themselves in a web of gaudy fashions and artificial entertainments).

I was especially struck by an early scene in which Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence) and Peeta Mellark (Josh Hutcherson), the victors of the first film’s Hunger Games, are compelled to show their feigned happy-ever-after love on live television. Instead of bringing them to the studio in the Capitol, Caesar Flickerman (Stanley Tucci), the flashy TV host, sends cameras to District 12 to catch the victors in their natural habitat — but the cameras are either automated or operated by remote control, and the sight of Katniss and Peeta forcing smiles and maybe even a kiss for a couple of robots, while the intended audience sits somewhere unseen miles away, really drives home the fact that Katniss and Peeta are caught up in a dehumanizing system and engaged in a hollow enterprise.

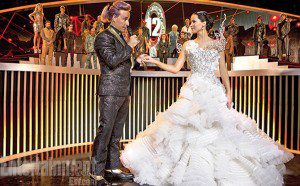

(Naturally, scenes like this raise questions about how the actors — not the characters, but the actors — feel about, or deal with, the publicity machine that they themselves are caught up in. When Katniss, much later in the film, glides onstage wearing a wedding dress during one of the new Hunger Games’ pre-publicity events, it is impossible now not to remember how Lawrence tripped on the steps while going to receive her Oscar earlier this year, and how gracefully, and naturally, she dealt with the faux pas. Katniss, needless to say, would not have fared so well in a similar situation.)

(Naturally, scenes like this raise questions about how the actors — not the characters, but the actors — feel about, or deal with, the publicity machine that they themselves are caught up in. When Katniss, much later in the film, glides onstage wearing a wedding dress during one of the new Hunger Games’ pre-publicity events, it is impossible now not to remember how Lawrence tripped on the steps while going to receive her Oscar earlier this year, and how gracefully, and naturally, she dealt with the faux pas. Katniss, needless to say, would not have fared so well in a similar situation.)

The story itself is a bit of an odd jumble of things. The first part of the film follows the events of the previous film quite naturally, as the victors deal with the tension between their private feelings (or lack thereof) for each other and their public obligations as propaganda puppets for the Capitol. The second part, which sees Katniss and Peeta compelled to participate in the Hunger Games all over again — along with victors from many of the previous Hunger Games — plays a bit like a rehash of the first film, albeit with some important differences (more on that in a minute). And then, well, there’s that abrupt ending, which takes the story in an all-new direction that you don’t quite expect (at least if, like me, you haven’t read the books).

But while I do have my doubts about the film’s narrative structure, I must say that the main thing that stayed with me on the trip home after seeing the film was the characters themselves, who are believably vulnerable, resourceful, devious and empathetic as the story demands. It would be easy to dismiss the love triangle between Katniss, Peeta and Gale Hawthorne (Liam Hemsworth) as just another of those young-adult-novel things, but there’s none of that silly posturing that Edward and Jacob engaged in throughout the Twilight films (come to think of it, I’m not sure that Peeta and Gale even share any scenes in this film), and Lawrence absolutely sells you on the idea that Katniss’s indecision is driven, in part, by her need to be strong for her family and do whatever it takes to help them survive. (Thankfully, Katniss has none of Bella Swan’s irritating passivity.)

And in a plot twist that really drives home the degree to which this franchise was inspired by Survivor and other so-called “reality TV” shows, Katniss and Peeta manage to form an “alliance” with other contestants when this film’s Hunger Games begin. The most interesting of the bunch may be Finnick Odair (Sam Claflin), a preening peacock of a guy whose trustworthiness is sometimes in doubt, but who happens to be very protective of an old woman named Mags (Lynn Cohen). (In the past, the Hunger Games have always been fights-to-the-death between teenagers, but the contestants in this year’s games consist entirely of victors from the previous games, and so, as a result, most of this year’s contestants are adults, i.e. people who won the games years or even decades ago.) Another of their allies is a guy named Beetee (Jeffrey Wright), a technical whiz with a knack for electrocution who always looks for flaws in “the system”.

And in a plot twist that really drives home the degree to which this franchise was inspired by Survivor and other so-called “reality TV” shows, Katniss and Peeta manage to form an “alliance” with other contestants when this film’s Hunger Games begin. The most interesting of the bunch may be Finnick Odair (Sam Claflin), a preening peacock of a guy whose trustworthiness is sometimes in doubt, but who happens to be very protective of an old woman named Mags (Lynn Cohen). (In the past, the Hunger Games have always been fights-to-the-death between teenagers, but the contestants in this year’s games consist entirely of victors from the previous games, and so, as a result, most of this year’s contestants are adults, i.e. people who won the games years or even decades ago.) Another of their allies is a guy named Beetee (Jeffrey Wright), a technical whiz with a knack for electrocution who always looks for flaws in “the system”.

And then there’s the deeply pissed-off Johanna Mason (Jena Malone), who responds to their plight with don’t-give-a-bleep attitude. (Just as fans of this franchise have debated whether or not the film and its promoters are indulging in the very sort of crowd-numbing spectacle that the books critiqued, so too they might want to debate whether the bleeping in this film is diegetic or non-diegetic; i.e., are we hearing the bleeps that the Capitol’s TV producers would have imposed on her interview, or, given that the camera seemed to be giving us the filmmakers’ perspective and not the TV audience’s perspective when she gave that interview, was the bleep imposed directly on the film itself so as to avoid an R rating? Does the film merely depict the act of censorship, or does it actively participate in censorship?)

Even some of the minor characters have some interesting nuances this time. Effie Trinket (Elizabeth Banks), the woman whose job it is to select and prepare the Hunger Games contestants for their public appearances and whatnot, was always a campy caricature of the sort of people who thrive on celebrity culture, but here she shows some genuine emotion when it is revealed that Katniss and Peeta must participate in the Hunger Games again, instead of living the life of luxury that they had been promised the first time ’round. You don’t want to feel too sad for Effie, who has after all enjoyed a position of privilege within a brutal social institution, but, as superficial as she is, she does seem troubled by this latest turn of events; you can feel her sense that there’s something wrong with the way the Hunger Games are being handled this time, and, given that Katniss and Peeta are stuck in this situation, you’re kind of grateful on their behalf for any expression of genuine sympathy that comes their way, whatever its source.

Even some of the minor characters have some interesting nuances this time. Effie Trinket (Elizabeth Banks), the woman whose job it is to select and prepare the Hunger Games contestants for their public appearances and whatnot, was always a campy caricature of the sort of people who thrive on celebrity culture, but here she shows some genuine emotion when it is revealed that Katniss and Peeta must participate in the Hunger Games again, instead of living the life of luxury that they had been promised the first time ’round. You don’t want to feel too sad for Effie, who has after all enjoyed a position of privilege within a brutal social institution, but, as superficial as she is, she does seem troubled by this latest turn of events; you can feel her sense that there’s something wrong with the way the Hunger Games are being handled this time, and, given that Katniss and Peeta are stuck in this situation, you’re kind of grateful on their behalf for any expression of genuine sympathy that comes their way, whatever its source.

And while I wouldn’t say that President Snow (Donald Sutherland) shows much depth this time — he’s still an out-and-out villain, capable of dictating the worst atrocities — there are some interesting scenes in which he discovers that his granddaughter has begun to emulate Katniss, wearing her hair in a braid like Katniss does and so on. Snow doesn’t react to this in his granddaughter’s presence, but you can sense how this symbolic infiltration of his home motivates his efforts to do something about the threat posed by Katniss and everything she stands for.

Ah, but what does Katniss stand for? She and Peeta stood up to the establishment at the end of the first Hunger Games and, because they were popular, they were both allowed to live (even though the rules dictate that only one contestant should come out alive). But Katniss simply wanted to survive, and now she learns that other people are standing up to the government and defying it in imitation of her — and sometimes these people are killed for doing so, even in Katniss’s presence. This traumatizes her, and it’s a thread that runs through this film right to the end: Katniss never wanted to be the catalyst for anyone else’s death — she volunteered for the games in the first film in order to save her sister’s life — but the graffiti slogans painted on the walls and the riots that show up on the security guards’ video screens tell her that something bigger is happening now.

Ah, but what does Katniss stand for? She and Peeta stood up to the establishment at the end of the first Hunger Games and, because they were popular, they were both allowed to live (even though the rules dictate that only one contestant should come out alive). But Katniss simply wanted to survive, and now she learns that other people are standing up to the government and defying it in imitation of her — and sometimes these people are killed for doing so, even in Katniss’s presence. This traumatizes her, and it’s a thread that runs through this film right to the end: Katniss never wanted to be the catalyst for anyone else’s death — she volunteered for the games in the first film in order to save her sister’s life — but the graffiti slogans painted on the walls and the riots that show up on the security guards’ video screens tell her that something bigger is happening now.

And the question that lingers at the end of this film — one of them, anyway — is whether the brewing revolution is going to try to use Katniss just as the Capitol has been using her. And if Katniss fails to comply with the revolution the same way she failed to comply with the Capitol, could the revolution turn on her the same way the Capitol did? Fans of the books presumably know the answers to these questions, but as for me, I’ll happily wait to see how the next two films tie up these loose threads.

Incidentally, I see that I have not yet mentioned Philip Seymour Hoffman, who makes his first appearance in this franchise as Plutarch Heavensbee, the man who has taken over as Head Gamemaker following the forced suicide of Seneca Crane at the end of the first film. Well, to be honest, I don’t have much to say about his performance, except that I was amused to see that this is the first film to feature both Hoffman and Toby Jones (as one of the games’ announcers), the two actors who played Truman Capote in almost-simultaneous films seven or eight years ago.

I was also struck by the fact that the Hunger Games shown in this film had very little of the person-on-person violence that the first film had. There’s a bit of that, yes, but the primary focus during this section of the film is on the alliance-building (and the inevitable question of which alliance member will turn against the others first, once the alliance has served its purpose). The main threat to the game’s participants this time seems to come in the form of deadly threats that are added to the environment by the Gamemakers, and I got a kick out of how Catching Fire almost played like a series of horror-movie homages (the fog! the birds! the… okay, I don’t think there actually is a film called The Monkeys, but you get the idea).

I was also struck by the fact that the Hunger Games shown in this film had very little of the person-on-person violence that the first film had. There’s a bit of that, yes, but the primary focus during this section of the film is on the alliance-building (and the inevitable question of which alliance member will turn against the others first, once the alliance has served its purpose). The main threat to the game’s participants this time seems to come in the form of deadly threats that are added to the environment by the Gamemakers, and I got a kick out of how Catching Fire almost played like a series of horror-movie homages (the fog! the birds! the… okay, I don’t think there actually is a film called The Monkeys, but you get the idea).

Finally, I was also struck by the abruptness of the ending, and the framing of the film’s final shot. Given that the third book, Mockingjay, is being turned into two films (just like the final books in the Harry Potter and Twilight series), it seems to me that we could have a situation here in which the Hunger Games franchise gives us two cliffhanger endings in a row, and I’m not sure whether any other franchise has ever done that. The fourth to seventh Harry Potter films all ended on sad notes, with the death of a significant character, but each film had its own arc and ended with some sort of resolution, except perhaps for Deathly Hallows Part 1. Likewise, I vaguely recall that each of the Twilight films was a self-contained story, with the partial exception of Breaking Dawn Part 1. And the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit films may have ended with lots of loose threads, but there was still a sense of closure, almost a chance to pause and take a breath before moving on to the next part of the story.

But maybe I’m forgetting something. Maybe the ending to Catching Fire is more like the endings to those other films than I remember. For now, though, all I can say is that I totally understand where the Empire Strikes Back comparisons are coming from — and that the next film in this series can’t come soon enough.

November 24 update: Louise Freeman at Hogwarts Professor opts for a different sequel analogy, and compares this film to Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.