For over two decades now, my official second-favorite film of all time has been The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985). An image from the film’s final scene is embedded in the banner at the top of every post on this blog. Thirteen months ago, I selected this film for a screening and discussion group at a film festival in Texas. Six weeks ago, on Boxing Day, I even got to see the film on the big screen for the first time ever — a 35mm print, even! — as part of the VanCity Theatre’s year-long Woody Allen series.

For over two decades now, my official second-favorite film of all time has been The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985). An image from the film’s final scene is embedded in the banner at the top of every post on this blog. Thirteen months ago, I selected this film for a screening and discussion group at a film festival in Texas. Six weeks ago, on Boxing Day, I even got to see the film on the big screen for the first time ever — a 35mm print, even! — as part of the VanCity Theatre’s year-long Woody Allen series.

So I’m something of a fan — not just of this particular film, but of Woody Allen’s films in general, at least for the first two decades or so of his directing career. In truth, the last film directed by Woody that I really enjoyed was Bullets over Broadway (1994), and the last film to star him (or at least his voice) that I really enjoyed was the DreamWorks comedy Antz (1998). Since then, it has seemed to me that most of his films recycle themes that he did a better, more interesting job of exploring in his earlier films; and it has sometimes seemed to me that the moral urgency he brought to films like Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989) has given way to a more cynical complacency in similarly-themed films like Match Point (2005).

But even my enthusiasm for his earlier films has waned somewhat. Around the turn of the millennium, I bought a bunch of Woody Allen films on DVD — including nearly everything he directed in the 1970s and 1980s — and when I watched them all together, I was struck by the way his dialogue frequently consisted of characters describing each other. Whether funny or serious, his films did not show so much as they told. And this realization has tainted my view of his films ever since.

Not The Purple Rose of the Cairo, though. That film is just brilliant. Funny, creative, romantic, bittersweet, magical, and strikingly profound. In the words of its main character, it’s “deep, and probably complicated.”

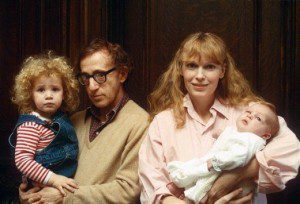

So when Dylan Farrow, one of two children adopted by Woody and his then-muse Mia Farrow, began and ended her recent open letter — in which she accused her father of molesting her 22 years ago — by asking the question, “What’s your favorite Woody Allen movie?”, I not only knew my answer right away, I also thanked heaven that The Purple Rose of Cairo was filmed before Dylan had even been born.

There is nothing particularly new about Dylan’s allegations, beyond the fact that she is making them publicly herself; until now, other members of her family had transmitted them. (She also goes into more detail than I have seen before, but then, I haven’t trawled through the court transcripts from 20+ years ago.) So why is she giving them new life now? I have a few thoughts about that, but first, about the allegations:

The first thing I want to say is that I don’t doubt for a second that Dylan believes every word she says. Someone clearly traumatized her all those years ago, when the allegations were first made during a particularly heated custody battle between her mother and her father, the latter of whom had just left the mother for one of the mother’s other (and much older) adoptive daughters. Dylan was only seven at the time, and has had to live with the memories of that experience ever since.

But memory itself is a complicated thing. John Dominic Crossan devotes several pages to the subject in The Birth of Christianity, and notes several ways in which things that did not actually happen can sometimes become lodged in a person’s brain as “memories”. One study he cites looked at how students were asked three times, over two and a half years, to describe how they first heard about the Challenger explosion (the first questionnaire was filled out the day after the explosion itself). The study found that the memories were very much in flux immediately after the event, but then stabilized — and that the confidence with which someone claimed to remember something often bore no relationship to the accuracy of the memory itself. At the end of his survey, Crossan concludes: “I do not think that eyewitnesses are always wrong; but, for example, if eyewitness testimony is a prosecution’s only evidence, there is always and intrinsically a reasonable doubt against it. Always.”

So in light of all that, I cannot simply take the allegations against Woody Allen at face value, not unquestioningly, especially when I read things like this:

On April 20, 1993, a sworn statement was entered into evidence by Dr. John M. Leventhal, who headed the Yale-New Haven Hospital investigative team looking into the abuse charges. An article from the New York Times dated May 4, 1993, includes some interesting excerpts of their findings. As to why the team felt the charges didn’t hold water, Leventhal states: “We had two hypotheses: one, that these were statements made by an emotionally disturbed child and then became fixed in her mind. And the other hypothesis was that she was coached or influenced by her mother. We did not come to a firm conclusion. We think that it was probably a combination.”

Leventhal further swears Dylan’s statements at the hospital contradicted each other as well as the story she told on the videotape. “Those were not minor inconsistencies. She told us initially that she hadn’t been touched in the vaginal area, and she then told us that she had, then she told us that she hadn’t.” He also said the child’s accounts had “a rehearsed quality.” At one point, she told him, “I like to cheat on my stories.” The sworn statement further concludes: “Even before the claim of abuse was made last August, the view of Mr. Allen as an evil and awful and terrible man permeated the household. The view that he had molested Soon-Yi and was a potential molester of Dylan permeated the household… It’s quite possible —as a matter of fact, we think it’s medically probable—that (Dylan) stuck to that story over time because of the intense relationship she had with her mother.” Leventhal further notes it was “very striking” that each time Dylan spoke of the abuse, she coupled it with “one, her father’s relationship with Soon-Yi, and two, the fact that it was her poor mother, her poor mother,” who had lost a career in Mr. Allen’s films.

And it is because the nature of memory is so malleable — especially, one would think, in the mind of a child — that I also think it was deeply irresponsible of Nicholas Kristof, an old friend of the Farrow clan who posted Dylan’s letter to his blog, to write in his accompanying column that people who praise Woody Allen’s films are “accusing Dylan either of lying or of not mattering.” Nonsense. It is possible — not easy, to be sure, but certainly possible — to believe that Dylan matters and to believe that she is not lying and that her allegations against her adoptive father are not true.

And that’s before we get to the question of whether it is possible to praise an artist for his work while remaining agnostic on allegations that have arisen from the artist’s personal life. Kristof writes: “The standard to send someone to prison is guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, but shouldn’t the standard to honor someone be that they are unimpeachably, well, honorable?” There is no question that what Woody did by leaving Mia for her daughter was very very wrong, but, well, as Rod Dreher points out, very few artists would ever be honoured for anything if being “unimpeachably honorable” were the standard that they all had to live up to. Mia Farrow reportedly remains on friendly terms with her Rosemary’s Baby director Roman Polanski, and he actually pleaded guilty to statutory rape in the late 1970s — but he continues to make films that win critical acclaim and even, in 2003, an Academy Award for Best Director. Should Woody Allen be held to a higher standard than Polanski simply because he has been accused of something but not found guilty of it?

So why are these old allegations back in the news now? Why did Mia revive the allegations in Vanity Fair in October, paving the way for her son Ronan’s tweets in January and, now, Dylan’s open letter? Two possible reasons come to mind.

First, Mia Farrow’s brother — Dylan and Ronan Farrow’s uncle — was himself convicted of child molestation and sentenced to prison for the crime last year. If Mia truly believes that Woody Allen is also guilty of that crime, then it must deeply upset her that her brother was caught and punished while Woody was not.

Second, and more importantly, after years of toiling away in obscurity, Woody Allen has been on something of a career upswing over the last several years, starting with the aforementioned Match Point. Just over two years ago, Midnight in Paris became the top-grossing film of his entire career — though Box Office Mojo estimates it ranks a still-respectable 7th place (out of over 40 films) when you adjust the figures for inflation. And now, Woody Allen and two of the actresses in his latest film, Blue Jasmine, have been nominated for Oscars — and Cate Blanchett, in particular, has been winning awards all over the place for playing the title character. Hence, the Golden Globes tribute (which Mia Farrow arguably participated in, by approving the use of footage of her from The Purple Rose of Cairo). And hence, the fact that Dylan Farrow pointedly addresses Blanchett by name in her open letter.

What makes this situation even stickier is the fact that Blanchett’s character in the film has seemed, to some observers, to be loosely (but perhaps subconsciously) modeled after Mia Farrow herself. Spoiler alert: Jasmine is a formerly well-to-do woman who lost everything when her husband was convicted of financial misdeeds and killed himself in prison, and the film ultimately reveals in flashbacks that her husband was arrested after she turned him in as an act of revenge. And why did she want revenge? Because he was about to leave her for a much younger woman.

When I first saw the film, I wondered if Woody was trying to feel sympathy for the wronged woman (not unlike how, say, Terrence Malick based To the Wonder partly on his own former marriage and tells the story primarily from the wife’s point of view). But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that his portrayal of Jasmine was a rather punishing one. Notably, there is a scene where Jasmine’s son tells her he wants nothing to do with her, because she ruined his life; it was not hard to imagine that Woody, who had lost contact with his own biological and adopted children, was wishing that his children had abandoned their vindictive mother instead.

Now, however, I learn from an article by Robert B. Weide, director of Woody Allen: A Documentary (2012) and one of the Golden Globes tribute’s editors, that one of Woody’s children has actually come back to him in recent years:

Moses Farrow, now 36, and an accomplished photographer, has been estranged from Mia for several years. During a recent conversation, he spoke of “finally seeing the reality” of Frog Hollow [Mia Farrow’s home in Connecticut] and used the term “brainwashing” without hesitation. He recently reestablished contact with Allen and is currently enjoying a renewed relationship with him and Soon-Yi.

So who knows, perhaps that scene in Blue Jasmine was inspired, in part, by the fact that one of the three people who are legally the children of Woody Allen and Mia Farrow has actually, in some sense, taken his father’s side and not his mother’s, now. It certainly adds an interesting wrinkle to the whole story. And now that the other two children have said their piece, I can’t help wondering if Moses will chime in.

Whatever happens, though, there’s no denying that this is an ugly situation, and that Dylan Farrow has been an innocent victim in all this. It’s impossible to say who’s more to blame: Woody Allen has never hidden his interest in younger women (going so far as to cast Mariel Hemingway as his teenaged lover in Manhattan), and a number of his earlier films include child-molestation jokes that may have sounded edgily humorous at the time but leave a sour taste now; as Matt Zoller Seitz has pointed out, even if Woody is innocent of any wrongdoing with Dylan, the presence of these themes makes him a perfect target for these sorts of accusations. And Mia Farrow sometimes seems so desperate to distance herself and her brood from Woody that she’ll say anything; witness, for example, how she claimed in that Vanity Fair story last year that she had been cheating on Woody with her ex-husband Frank Sinatra (who was married to another woman, now his widow, at the time), and that Ronan Farrow, the biological child shared by Woody and herself, might not actually be Woody’s.

Whatever. As Cate Blanchett said the night after Dylan’s open letter went public, I hope the various people involved can find some resolution and peace some day.

And for now, no, the allegations have not disrupted my love for The Purple Rose of Cairo any more now than they did two decades ago. It’s still a brilliant film, no matter what the people who made it did, or didn’t do, when the cameras weren’t rolling.

February 5 update: Moses Farrow has, indeed, chimed in and come to Woody Allen’s defense — and he makes some startling claims about Mia Farrow.