Warning: This review will discuss several major spoilers, including the ending.

Christian films have a bad reputation, and it is often quite justified. But as one who has been involved with church-drama ministries and the like, I have never been able to dismiss the genre entirely. And that’s why I have made a point of trying to look for the positive elements in films like, say, the ones produced by the Kendrick brothers (Facing the Giants, Fireproof, Courageous).

Christian films have a bad reputation, and it is often quite justified. But as one who has been involved with church-drama ministries and the like, I have never been able to dismiss the genre entirely. And that’s why I have made a point of trying to look for the positive elements in films like, say, the ones produced by the Kendrick brothers (Facing the Giants, Fireproof, Courageous).

As I have argued before, there is nothing wrong with a Christian “niche”. Christians, like other groups of people, have special needs and interests, and sometimes they require special kinds of films that people outside our community won’t “get”.

Films like the ones made by the Kendricks seem, to me, to fit into that category. Rather than pit Christians against the outside world, they focus on helping people to become better parents and spouses, etc., and while they clearly do this within a Christian paradigm, they are at least open to the possibility of friendship and camaraderie between Christians and people outside the church.

Could their films be better? Sure, and I would argue that each of their films has been an improvement on the last. Are they a bit preachy or ministry-oriented? Sure, but what’s wrong with that? Compared to, say, the typical Billy Graham film, which ends on a fairy-tale note where the protagonist finds Jesus and lives happily ever after, I have definitely appreciated the way the Kendricks have tended to put moments of decision in the middle of their films, so that they can focus on the long, hard task of living up to those commitments after they are made.

There is, however, a problem with Christian “ghettos”, and with films that pander to the Christian community by encouraging a sort of us-vs.-them way of thinking.

And that’s why it pains me to see that God’s Not Dead — a sloppily written, badly argued, unevenly acted film about a first-year college student who tries to prove the existence of God within weeks of setting foot on campus — has been performing so well at the box office, to the point where it recently passed Courageous to become the top-grossing film ever made by and for evangelicals. If this becomes the standard for all Christian films to come, then the genre is truly in deep, deep trouble.

Where to begin?

Well, for starters, there’s the set-up: a philosophy professor named Jeffrey Radisson (Kevin Sorbo) tells his students on the very first day of class that he’s going to give them all very bad marks if they don’t sign a piece of paper saying “God is dead”.

Everyone in the classroom complies, except for Josh Wheaton (Shane Harper), a student whose name is a not-so-subtle nod to professional apologist Josh McDowell and the “evangelical Mecca” of Wheaton, Illinois, home to various schools, publishing firms and Christianity Today. (Okay, technically Christianity Today is across the highway in Carol Stream, Illinois, but you get the idea.)

Radisson taunts Josh for his beliefs and challenges him to prove that God exists, in a series of in-class presentations. Josh accepts the challenge, and then, lo and behold, manages to do so in the space of… a week or less. (There’s a key scene, set on a Thursday, in which Josh tells someone he has bought two tickets to a Newsboys concert that will take place “next Friday”. And all three of Josh’s in-class presentations take place between that scene and the climactic concert.)

Has there ever been a philosophy professor this insulting, this bullying, this manipulative to his own students? Perhaps. And I could almost roll with the idea that Radisson had been baiting his class to see if anyone would rise to the challenge the way Josh does. Maybe Josh, by standing up to his Radisson, would turn out to be just the kind of student Radisson was really looking for, or something.

But no. The film utterly lost me in a scene after Josh’s first in-class presentation, in which Radisson catches him in the hall, grabs him from behind, and makes various angry threats if Josh dares to go on “humiliating” him in front of the class. I simply could not believe that a philosophy professor — especially one who is supposedly next in line to head the entire department — would expose his insecurities so nakedly to one of his students like that (and so early in the school year, at that).

Nor could I believe that a philosophy professor would be as, well, stupid as this one. In all of the debates and discussions that I have had with believers and unbelievers over the years, I have rarely encountered anyone who came even close to resembling the straw man presented here.

For one thing, I wasn’t quite convinced that any professional philosopher would include Richard Dawkins on a list of atheist philosophers. On a list of atheists, sure. But Dawkins is a biologist by training. Dawkins might write a lot of popular books about atheism, but would any introductory philosophy professor waste a minute of his time on a biologist with strong opinions when he could be introducing his students to actual philosophical concepts or modes of discourse?

In later scenes, Radisson goes on to gloat that atheists like Stephen Hawking are far more brilliant than first-year college students — but, again, Hawking is a scientist, a theoretical physicist to be precise, and not a philosopher. (And as my friend Steven D. Greydanus has pointed out, Hawking, while famous, isn’t necessarily even the greatest mind of our time, much less of all time as Radisson asserts.)

And then, when Josh makes his actual presentations, Radisson never offers any of the obvious rebuttals to some of Josh’s typical first-year arguments.

When Josh quotes that Dostoevsky line about how everything is permissible without God, Radisson never makes the obvious rejoinder that everything is permissible with God, depending on what one believes about God, so how is belief in God a guarantee of absolute morality? (Exhibit A: suicide bombers. Or, closer to home, Exhibit B: the biblical God did tell Abraham to sacrifice his son on an altar, did he not?)

Radisson does, at least, make a fleeting comment about natural disasters following Josh’s argument that God permits evil because of free will, but he never puts two and two together to underscore the fact that most natural disasters are not, in fact, caused by human agency and are therefore not traceable to free will.

And then, in the third and final in-class presentation, Josh suddenly exhibits a confidence that he never had before, and he decides to get Radisson all pissed off in a way that will force him to blow his temper in front of the class, in a scene that was such a blatant rip-off of A Few Good Men (1992) that I could not help but laugh out loud. (I half-expected, half-hoped the characters would start quoting actual dialogue from that film, just because it would have made the scene even funnier.)

And note, here, that Josh wins the argument not through logic but by swaying the class, and its perception of their teacher, emotionally. Radisson is wrong not because he has worse arguments, but because he has messed-up motivations for his beliefs.

So here we have a film that pretends to be about philosophy, but really has no idea what philosophy is all about — and it’s being pitched to Christian audiences as some sort of grand statement about the validity of belief or something.

What it really is, of course, is a lot of tribal chest-thumping. And it’s remarkable, in that light, to see how “the tribe” is defined within this film.

For one thing, I don’t think we ever — ever — see Josh get involved with any sort of Christian community once he arrives on campus.

When I went to university, I checked out groups like InterVarsity Christian Fellowship while friends of mine went to Navigators, and I got to know chaplains from the Baptist and Pentecostal denominations, besides. (It helped that my university was home to Regent College, one of the top evangelical graduate schools in the world. I spent a lot of time in their library, in their bookstore, and attending their public lectures.)

But Josh? Well, he sits inside an empty church at one point, and the pastor happens to walk through the sanctuary, spot him, and speak to him briefly. Do the two characters actually know each other, apart from that? I don’t think so, but maybe I missed something.

Josh also has a girlfriend, who he has apparently been seeing ever since they met at a Newsboys concert six years ago (like, when they were only 12 or something?). But she breaks up with him as soon as she realizes he’s serious about debating his professor, in another scene that was so abruptly handled that I burst out laughing.

Matters are complicated by the fact that nearly everyone in this film has nasty, mean, unbelieving parents — and if they don’t (i.e. if the parents are actually good people), then it’s because the younger characters are, themselves, nasty, mean and unbelieving. Even the ex-girlfriend tells Josh that her parents told her to leave him long ago.

And yet we never see the parents of Josh himself. Josh mentions once or twice that his parents, too, think he shouldn’t jeopardize his academic career by taking on his atheist professor, but we never see any evidence of this disagreement directly. Why not?

Maybe making the hero’s own parents mean and nasty would have been going too far. Or maybe the filmmakers felt Josh’s parents would have been at least sympathetic about it, but they didn’t know how to handle that kind of ambivalence onscreen.

To be fair, there is a hint of ambivalence in one of the other parent-child relationships in the film, in a subplot involving a female Muslim student with a controlling father.

Ayisha (Hadeel Sittu), the student in question, wears not just a head-covering but a face-covering on the way to and from school, to satisfy her father (oddly, the rest of her attire from the shoulders down is utterly Western) — and there is a scene in which her father picks her up and says he understands how difficult it can be to live “apart” from the people who surround her every day at school.

This subplot could have offered some interesting parallels between the evangelical Christian experience and the conservative Muslim experience (especially given that producer David A.R. White, who plays the pastor, grew up as a Mennonite preacher’s kid and wasn’t allowed to see movies at all while he was growing up).

But no: instead we discover that Ayisha is actually a closeted Christian who listens to Franklin Graham podcasts and lives in justifiable fear that her father will overreact if he learns about her true religious affiliation. So, the film falls right back into that mean, nasty parents versus good Christian children paradigm again.

This, again, raises all sorts of questions about the definition of religious community in this film: We never see Josh take part in any sort of religious community, and we never see Ayisha take part in any sort of community either. How did this Muslim girl with the overprotective father first hear the gospel? What persuaded her to switch sides? The movie doesn’t know and/or doesn’t care, and apparently doesn’t think we should either.

Eventually, all the movie’s various threads — and there are a lot of them, several of which the film doesn’t even try to tie together until maybe an hour into the story — come together at the aforementioned Newsboys concert. And this, it seems, is how the film understands evangelical community: a bunch of people going by themselves to a rock concert, basking collectively in the glow of pop-culture celebrity.

Not only do the Newsboys play themselves in this film, but one of the Duck Dynasty guys appears on a screen at the concert and tells everyone in the audience to take out their cell phones and spam everyone they know with text messages declaring “God’s not dead.” This, he says, is how “we’re going to tell Jesus we love him.” (And then the film’s closing credits tell people in the theatre to go and do likewise.)

Oh, that reminds me of another problem with this film: the way both Josh and the film as a whole assume that any proof for the existence of God must necessarily constitute proof for the existence of Jesus and the rest of the Christian belief system.

The fact that there are so many religions — the fact that so many people believe in God without subscribing to Christian beliefs about a certain historical person named Jesus — should tip us off to the fact that there is an entirely separate discussion to be had there, beyond abstract arguments for and against the existence of a Creator.

But unless I missed something, Josh’s in-class presentations never really get into that. Instead, after he has his A Few Good Men moment with Radisson, one of his fellow students — from the People’s Republic of China, no less — tells Josh he now wants “to follow Jesus.” Because, um, three freshman debates about the existence of God in the space of a week would automatically make someone who grew up in an officially atheist country suddenly buy the whole Christian kit and caboodle, right?

There are countless other problems with this film, from the implausibly sophisticated graphics that Josh uses in his PowerPoint presentation, to his invocation of “noted author Lee Strobel” (a journalist with a law degree, hardly a philosopher or even an academic of any sort), to the film’s depiction of a vegetarian atheist blogger who “ambushes” meat-eating Christian celebrities to ask them obvious questions that they have ready answers for. (I think we’re supposed to believe that her blog is very popular, but it’s hard to see why it would be.)

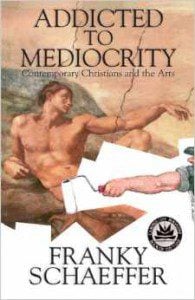

Oh, and in one of his graphics, Josh uses the image of God creating Adam that Michelangelo painted for the Sistene Chapel — but unless my eyes deceived me, the Adam in Josh’s graphic has no genitals. Honestly, people, if you don’t want us to think your Christian film is mediocre, the last thing you should do is employ images that remind us of the cover art for Frank Schaeffer’s book Addicted to Mediocrity.

Oh, and in one of his graphics, Josh uses the image of God creating Adam that Michelangelo painted for the Sistene Chapel — but unless my eyes deceived me, the Adam in Josh’s graphic has no genitals. Honestly, people, if you don’t want us to think your Christian film is mediocre, the last thing you should do is employ images that remind us of the cover art for Frank Schaeffer’s book Addicted to Mediocrity.

I also share Greydanus’s chagrin that Josh describes Georges Lemaître, the man who first proposed what we now know as the Big Bang theory, as “a theist” rather than, y’know, as the Catholic priest that he actually was. Why play coy with that sort of detail? Is it because, as Greydanus suggests, the filmmakers really, really don’t want their evangelical target audience to think outside of their narrow sectarian comfort zone?

And Professor Radisson is simply never a remotely believable character. At all. He’s a smart guy — except he has no idea how to defend his own atheism against a college freshman’s fumbling use of warmed-over apologetics talking points. He hates God — but apparently he shacked up with a Christian girl because, y’know, the story needed to put a Christian woman in his home so that he could humiliate her, too.

And then the film does, y’know, what it does with him. Wow.

Honestly, I could write a full-length review just of that ending. The way the film celebrates the death of Radisson by capturing the car accident from multiple angles — including, if memory serves, a so-called “God shot” in slow motion, pointing straight down as his body flies up in the air and over the car. The way the film shows zero interest in letting us know if any of the onlookers at least called 911. The way the pastors who happened to be driving by immediately take charge of the situation, just so they can get a last-minute conversion, without even bothering to ask if any of the onlookers might be nurses or doctors or whatever. And so on, and so on.

The word “martyr” comes from a Greek root meaning “witness”, and in the early church it referred to people who witnessed for their faith by going willingly to their deaths. But this is the sort of film in which the uneducated Christian does all the witnessing and his supposedly educated atheist nemesis does all the dying — and while the film officially wants us to think that Radisson has gone to a better place so it’s all for his own good really, that’s not how it plays. This film celebrates the character’s violent dispatch — which, incidentally, coincides with the Newsboys concert where Josh is publicly acknowledged by the band itself, which I guess is supposed to be the film’s “Well done, good and faithful servant” moment. For all the talk of heaven, what this film really wants is rewards here on Earth.

I guess I should also say something about Dean Cain, since he’s one of the two “name” actors in this film. But honestly, I’m not sure what he’s doing here, apart from giving the film one more gratuitous subplot and the audience one more unbelievably vain, selfish atheist to boo and hiss — assuming they’re not laughing in disbelief at how badly written his character is. What does he bring to the table here? Seriously.

Honestly, there isn’t much to recommend this film.

I suppose it’s a sign of progress that a movie so popular with evangelicals is okay with the idea that the universe is billions of years old, and even with the idea that God might have created life using some sort of evolutionary process. (Josh doesn’t quite come out and endorse evolutionary theory, but the fact that he merely argues that God must have guided the evolutionary process is surely significant.)

And, um, it’s filmed fairly competently. It didn’t look or sound entirely out of place on a multiplex movie screen (though the ADR did stand out in a few scenes, and the font used in the titles sequences has been something of a cliché for a few years now).

And Sorbo has a really good voice. Honestly, at several points during this film, I found myself thinking that I would love to hear Sorbo do an audiobook or a radio play or something — anything but this film. So there’s that.

But on the whole, this movie really isn’t worth anyone’s time. And it’s startling to see that this film, of all films, has been so richly rewarded by the “faith-based market”. I shudder to think of what this bodes for the future of the genre.

Update: It turns out the writers of God’s Not Dead are Catholic, not evangelical — but the other filmmakers edited the specifically Catholic bits out of the script. From an interview that was just published by the National Catholic Register:

[Chuck] Konzelman: When writing the film, we deliberately adopted a tone of discourse that’s clearly an evangelical one. We added some Catholic “brushstrokes,” but they were ultimately cut. Originally there was a smidgen of Thomas Aquinas and a couple of other Catholic references, like the one regarding the Belgian physicist, [Father Georges Lemaitre], who developed the idea of the Big Bang, and we had a character mention that he was actually a Catholic priest, but they edited around it.

Sadly, Konzelman also repeats the “Noah is Gnostic” meme that I’ve been fighting the past few weeks. You can read my most recent thoughts on that subject here.