Donna Dickens has an amusing post up at Hitfix in which she begs Hollywood to “please stop character assassinating Ramses II”.

Donna Dickens has an amusing post up at Hitfix in which she begs Hollywood to “please stop character assassinating Ramses II”.

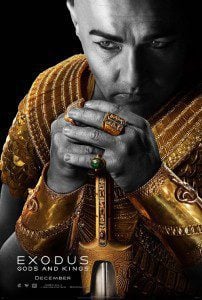

The Bible, you see, never says precisely who was the Pharaoh of the Exodus, but most big-screen versions of the story — from The Ten Commandments to The Prince of Egypt to Ridley Scott’s upcoming Exodus: Gods and Kings — have assumed it was Ramses II, one of the most powerful Pharaohs who ever lived.

There are reasons for this, which I’ll get to in a moment, but Dickens proposes an alternative theory. Instead of dating the Exodus to the time of Ramses, who lived in the 13th century BC, she proposes dating it to the time of Thutmose III, an accomplished Pharaoh in his own right who ruled in the 15th century BC.

Why so much earlier? Partly because I Kings 6:1 tells us that Solomon began building the Temple 480 years after the Israelites came out of Egypt, and that he did this during the fourth year of his own reign. So Solomon began his reign 476 years after the Exodus, and if you date the beginning of Solomon’s reign to about 970 BC, as Dickens apparently does, then all you have to do is add 476 years and — voila! — the Exodus took place in 1446 BC, right in the middle of Thutmose’s reign.

I used to subscribe to this theory, or at least a version of it, myself.

Thirty years ago, I wrote a “novel” about the life of Moses in which Thutmose III was Pharaoh when Moses went into exile, and his son Amenhotep II was Pharaoh when Moses came back and led the Hebrews out of bondage. Even better — and influenced, as I recall, by Halley’s Bible Handbook — I imagined that the Egyptian woman who adopted Moses was none other than Thutmose’s stepmother Hatshepsut, who was one of the very few women to rule Egypt as Pharaoh, fake beard and all.

So imagine my delight when I saw that Dickens had also proposed making Hatshepsut the adoptive mother of Moses!

Dickens, like me, imagines that Thutmose would have hated Hatshepsut for ruling in his place (she was initially supposed to be his regent, but when he became old enough to rule on his own, she held on to the throne), and that he would have “seethed” against her and her adopted son — so when Hatshepsut died and Thutmose became sole ruler of Egypt, Moses was no longer safe. Cue exile.

As it happens, I no longer subscribe to the idea that the Exodus (whatever we mean by that, historically) took place this early.

For one thing, the Old Testament frequently measures time in multiples of 40 years, and I currently lean towards the view that this unit of time basically represents “one generation”, so that when I Kings says Solomon began building the Temple “480 years” after the Exodus, it really means something like “12 generations”.

What’s more, Solomon’s reign itself is said to have lasted 40 years — just like his father David’s — and this, too, looks suspiciously rounded-up. (All of the subsequent kings have reigns of various lengths, but the reigns of David and Solomon — the two “Golden Age” kings — are suspiciously “perfect”.) So even if we can confidently say that Solomon’s son took the throne around 930 BC, we can’t necessarily say that Solomon began his own reign in 970 BC. He may have started quite a bit later, in which case the date of the Exodus would also have to move a bit later.

All of which makes dating the Exodus to Ramses’ day look more plausible.

At this point, I’m not sure if each filmmaker has his own historical reasons for making Ramses the villain,* or if they’re all just copying the precedent set by earlier films. But the reasons for making Ramses the Pharaoh are pretty straightforward.

First, the Bible itself claims that the Hebrews built a city called Ramesses, which most scholars have identified with Pi-Ramesses, a place that was substantially expanded during the reign of Ramses II when he made it his new capital.

And second, Ramses’ son Merneptah erected a stele in which he boasted that he had defeated the Israelites during a military campaign in Canaan. If the Israelites were already there in the Promised Land when Ramses’ son was Pharaoh, presumably they must have left Egypt no later than the reign of Ramses himself.**

Many people will argue that this whole conversation is ridiculous because there’s no historical or archaeological evidence that the Exodus ever took place. Personally, though, I’m inclined to think that something like what we read in the Torah did take place, if only because it seems unlikely that a nation would have created a past for itself in which everyone was a slave, or that the Israelites would have invented a leader for themselves who just happened to have an Egyptian name.

The story may have grown over time, and tribes that were not originally Israelite may have grafted themselves onto this nation, thereby retroactively inserting themselves into the story (see my post on the origins of Dan, the tribe from which Samson came). But I do think there’s a core of historical fact in there somewhere.

As for the question of who the Pharaoh in Moses’ day would have been, I have no strong opinions one way or the other. Ramses II is as good a candidate as any, and the fact that he’s one of the best-known Pharaohs does make him attractive from a dramatic point of view. (The many monuments he erected to himself have also given production designers plenty to work with.)

But I sympathize with those who wish that filmmakers would pick on somebody else. It does seem a shame that a Pharaoh who accomplished so much else in his lifetime should be known today primarily, or even exclusively, because of his highly speculative association with a story that, in its original form, never mentions him.

–

* It’s an open question whether Scott knows how to separate history from fiction in this case. When he first revealed that he was making Exodus, he said: “What’s interesting to me about Moses isn’t the big stuff that everybody knows. It’s things like his relationship with Ramses [II, the pharaoh]. I honestly wasn’t paying attention in school when I was told the story of Moses. Some of the details of his life are extraordinary.” Given that the Bible never mentions Ramses and secular history never mentions Moses, what “details” could Scott’s teachers have told him about?

** Interestingly, some of the more high-profile TV-movies about Moses — such as Moses the Lawgiver and the TNT miniseries Moses — have speculated that the Pharaoh of the Exodus was actually Merneptah. Ramses II therefore appears in those films as the Pharaoh who reigned when Moses went into exile.