I got an e-mail today from the folks behind The Song. Like most Monday-morning e-mails of this sort, it asks its readers to support a newly-released independent film by voting with their dollars as soon as possible, etc.

I got an e-mail today from the folks behind The Song. Like most Monday-morning e-mails of this sort, it asks its readers to support a newly-released independent film by voting with their dollars as soon as possible, etc.

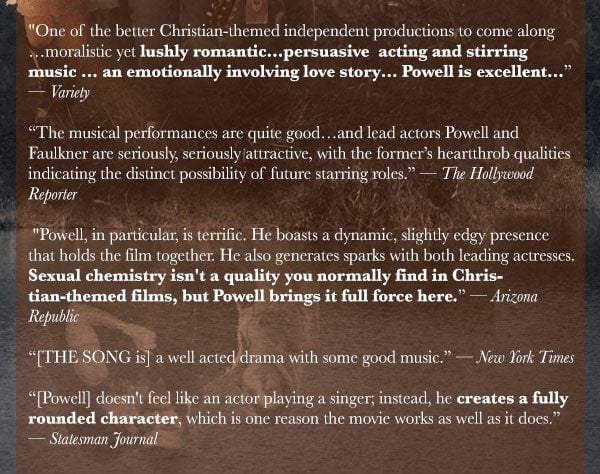

The e-mail also does something I don’t believe I have ever seen in an ad or message promoting a “faith-based” film before: it draws special attention to secular critics who have praised the film for the “sexual chemistry” between its lead actors.

The most significant quote in that regard comes from the Arizona Republic, and the e-mail highlights it in boldface: “Sexual chemistry isn’t a quality you normally find in Christian-themed films, but [lead actor Alan] Powell brings it full force here.”

You can read the full e-mail here, but this is the most significant bit:

A number of Christian critics, including myself, have already noted that the film deals more frankly with sexual issues — both within marriage and without it — than the typical “faith-based” movie. So that’s certainly an element worth talking about.

It’s still rather striking, though, to see a film like this draw attention to the fact that its lead actor “generates sparks” with two different women, as though that were part of the film’s entertainment value, in an e-mail aimed at conservative audiences.

The Song isn’t the only Christian film that seems to be comfortable with characters generating such sparks. The Left Behind reboot, which comes out this Friday, is quite different from the original straight-to-video version of that story in its portrayal of Hattie Durham, the flight attendant who is thisclose to having an affair with airline pilot Rayford Steele when the Rapture happens and interrupts their plans.

In the original film, Hattie was played by Chelsea Noble, a Christian whose husband, Kirk Cameron, is so serious about their marriage that he refuses to take off his wedding ring when he plays single men, or to kiss any actress other than his wife (who has served as a “kissing double” for him in films like Fireproof).

Fred Clark, in his scene-by-scene evisceration of the original Left Behind a few years ago, noted that Noble was unable to play Hattie convincingly partly because the viewer could tell that she was actively “judging” her character:

Mrs. Cameron doesn’t approve of Hattie Durham’s behavior here and she doesn’t want viewers to approve of it either.

That disapproval is evident here. And because we can see that disapproval, we can also see the person doing the disapproving — the actress Chelsea Noble. And since there isn’t room here for both the actress and the character, Hattie gets squeezed out. We can’t glean whatever it was that motivated Hattie to go to Rayford’s house and beg/threaten/negotiate for their future in this scene, because the only motivation we see here is Chelsea’s, not Hattie’s.

This is part of why actors so often say that they won’t or can’t or mustn’t judge the characters they play. It’s almost impossible to decide that you approve or disapprove of the character or the character’s actions without conveying that approval or disapproval instead of those actions. Such judgments can’t be made to fit inside of the story you’re trying to tell and they usually wind up taking both you and your audience outside of the story.

In the reboot, however, Hattie is played by Nicky Whelan, and while she vamps it up a bit when we first see her, you definitely get a sense of how the character, rather than the actress, is trying to present herself (especially to Rayford Steele).

What’s more, as Whelan herself said in a teleconference promoting the film a couple weeks ago, the Left Behind reboot — which tells only a fraction of the story that the original film told — actually gives Hattie a redemptive arc of sorts:

At the end you see some really redeeming qualities in Hattie, and at the start you’re not quite so sure about her. I could have played this quite hard and quite ruthless, and not bitchy but just very self-driven. But I think throughout the movie, you see her break down and what people really go through as humans when they’re faced with these problems, and in Hattie’s case, she really redeems herself on a lot of levels, personal levels, and you see that, and I think you can go away from the film with a bit of love for her, and I’m so grateful that Vic [Armstrong, the director] and I chose that as a way to let the movie end. Let me tell you, if we come back and make [part] two, I think she turns again. I mean, she might have bipolar [disorder]!

Now, to be sure, neither of these films comes out and embraces adultery, or any other form of sex outside of marriage. The moral framework of these stories remains intact. But both of these films are remarkably willing to let these characters express that side of themselves, as part of a more broadly empathetic approach to these characters.

Traditionally, Christian movies have been little more than illustrated sermons, and have avoided dealing with issues of temptation or titillation in anything but the most roundabout way, lest the illustrated sermon became a form of mere entertainment that tempts and titillates in its own way. But these recent films suggest that “faith-based” filmmakers are more open to just telling their stories in ways that feel at least somewhat believable, in ways that feel right for the stories they are telling.

This could be a sign of progress. Or it could be a sign that “faith-based” films are moving closer to the pure “entertainment” end of the spectrum. Either way, it suggests that something has changed — for both the filmmakers and their audience.