Bible movies were big in the silent era, which came to an end in the late 1920s, and they were big again in the 1950s, when pious spectacle was all the rage — but very few were produced during the two decades between those eras.1 Hollywood, in particular, seemed to lose interest in the genre entirely during this period. Nevertheless, a few films did at least touch on the genre, even if they did not commit to it fully.

Cecil B. DeMille, of course, produced two early sound films that flirted with biblical elements. The Sign of the Cross (1932) depicts the persecution of the Christians under Nero, which took place just a few years after the events of the book of Acts — but the film does not depict any actual biblical characters or events, with the exception of Titus, who comes to Rome bearing a letter from Paul. And then there was Cleopatra (1934), in which Herod the Great stirs things up between the Egyptian queen and her Roman suitor just a few decades before the events of the New Testament.

But both of those films take place outside the biblical timeframe. The only Hollywood film I’ve seen from this era that actually depicts any events from the Bible is, of all things, The Last Days of Pompeii (1935).2 Produced by Merian C. Cooper and directed by Ernest B. Schoedsack just two years after they made King Kong, the film — by its own admission — shares a title and a setting and little else with the 1834 novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton. The story breaks down into three parts that are roughly half-an-hour each, and while the first and last sections take place in Pompeii, the middle section takes place in Judea during the reign of Pontius Pilate (who is played by Basil Rathbone, four years before his first Sherlock Holmes movie).3

The story concerns a blacksmith named Marcus (Preston Foster) who loses his wife and infant son in an accident and, along the way, becomes a gladiator, convinced that money is the only thing that matters in the world so you might as well kill people to get it. At one point Marcus learns that he has orphaned a gladiator’s son, so he adopts the boy, Flavius, as his own — and then, when Marcus is wounded and informed that he will never be able to fight in the arena again, he decides to become a slave trader and accumulate enough money to run the arena some day.

Marcus’s pursuit of wealth takes him to Judea, where Pontius Pilate helps him to steal some horses and gold and thereby make his fortune (more on that in a minute). Marcus also has three close encounters with Jesus, who remains offscreen throughout: once, Marcus steps into a stable and is informed that “the greatest man in Judea” is sleeping there; later, he takes Flavius to be healed by Jesus; and then, apparently just a few days later, he sees Jesus carrying his cross through the streets of Jerusalem.

By that point Marcus has acquired the wealth that he was looking for, and so he leaves Jerusalem and returns to Pompeii — at which point the movie jumps ahead to the days immediately preceding the destruction of that city. (Nearly half a century separates the death of Jesus circa AD 30 from the destruction of Pompeii in AD 79, but everyone in the film looks maybe 20 years older at most.) Marcus is indeed the head of the arena that he wanted to be, but Flavius has turned against his father’s materialism and is secretly planning to help runaway slaves escape to an island where there is “no wealth, no people to enslave” and “no Roman soldier has ever set foot” — and somewhere in all this, Pontius Pilate pays Marcus and Flavius a visit.

The story reaches its climax when Flavius and the slaves are captured and sent into the arena. Marcus pleads with the local prefect to set Flavius free, but the prefect won’t allow it — and then the volcano erupts and everybody panics. Marcus, realizing the error of his ways (partly because a man pleads for his son’s life with the same words that Marcus used when asking Jesus to heal Flavius), decides to rescue other people rather than save his own wealth, and his efforts eventually cost him his life. Finally, as he lays dying in the street, Marcus has a vision of Jesus himself.

The disaster footage is the film’s big selling point, and in some ways it is reminiscent of the destruction of Skull Island at the end of Son of Kong, which the filmmakers had made just two years earlier. (Willis O’Brien, the stop-motion pioneer who worked on the Kong films, is listed in Pompeii’s credits as the film’s “chief technician”.) Statues topple, buildings collapse, and a river of mud and lava flows through the city — and as in many disaster movies over the years, the people who suffer the most seem to “deserve” it, like when a wealthy woman being carried in a litter pushes a poor woman out of her way, and is almost immediately crushed by some falling debris. (Of course, the debris falls on the servants who were carrying the wealthy woman, too.)

But the main attraction for me is the film’s inclusion of the biblical narrative, and I am intrigued by the fact that the filmmakers included it at all when it doesn’t really fit the period of Pompeii’s destruction. As I mentioned above, roughly 50 years went by between the death of Christ and the eruption of Mt Vesuvius, yet the characters seem to age only 20 years or so, if that. Why did the filmmakers warp history so? I can only speculate, but I wonder if the filmmakers felt that a story about the ancient Romans needed to be linked somehow to the rise of Christianity, similar to how Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus, set roughly one century before the events of the New Testament, begins with a reference to Jesus that the story doesn’t really need. It was not impossible back then to tell a purely secular story set in the ancient Roman world, but the biblical genre evidently exerted a pull on films set in that period, even in an era like the 1930s when full-fledged Bible movies weren’t really being made at all.

As noted, the film’s biblical elements revolve around Jesus, who interacts with the characters though he is never seen by the audience, and Pontius Pilate, who appears not only as the Roman official in Judea but as an old acquaintance who visits Marcus in Pompeii years later. And the film does some interesting things with these elements.

First, the film prepares us for the inclusion of Jesus in the story by having a female fortune-teller tell Marcus, before he sails for Judea, that Flavius will meet “the greatest man, greater than anyone yet known” there. “He will help the child when help is needed, and his spirit will direct the child,” says the fortune-teller. This is interesting on two levels: first, the film seems to affirm not just Christian miracle-working but pagan clairvoyance (which admittedly isn’t so hard when you recall how the birth of Christ was heralded by astrologers from the east in Matthew’s gospel); and second, while the young Flavius will indeed be healed by Jesus, he will grow up never knowing who Jesus was, and his efforts to set slaves free will stem from a general humanist impulse rather than any particular religious motive. The film thus suggests that the “spirit” of Jesus lies behind the quest for justice and freedom, but conscious religious affiliation with Jesus is not an essential part of that quest.

Second, Jesus is never depicted at all, with the exception of the very final shot, when Jesus appears as a transparent ghost-like figure whose appearance is still somewhat obscured. When Marcus takes Flavius to be healed by Jesus, the pivotal moment is shot essentially from Jesus’ point of view as Marcus approaches the camera and a bright light illuminates Marcus’s face. The film then wipes from the close-up to a wide shot of the crowd, and soon after that, the crowd walks offscreen (presumably following Jesus, who is hidden from our view) and leaves Marcus and Flavius standing or kneeling where they are. The use of a wipe here is interesting, as it leaves us wondering just how much time has passed since Marcus asked Jesus to heal Flavius — and also because there is another wipe at the very end of the film, when Marcus looks offscreen at Jesus and the film wipes to a wide shot of Marcus and Jesus looking at each other. In that case, no time seems to have passed at all, but the use of a wipe creates the sense that Jesus is being “revealed” to the audience.

Third, one of the film’s most persistent themes is the relationship between rich and poor, between material wealth and the spiritual kind. Jesus is identified by one character here as “a wandering healer” who is called “Master and Lord” by “all the poor people.” When Marcus comes to Judea, he meets with Pontius Pilate because he assumes Pilate is the “great man” that the fortune-teller prophesied — but of course, that just shows how Marcus’s pursuit of money and power has blinded him to the possibility that “greatness” can exist on a more spiritual plane. When Marcus makes a pit stop at a stable and is told that “the greatest man in Judea” is sleeping there, he scoffs, but is told that Jesus “was born in a stable.” Later, after Jesus has healed Flavius, Marcus tells one of Jesus’ followers that he would gladly give Jesus money in thanks, but the man says Jesus won’t take the money because he’s already “the richest man in the world.” And many years later, when Pilate visits Marcus and Flavius in Pompeii and confirms that Flavius isn’t just dreaming that he was healed by a man many years before, Marcus reveals that he is aware of Jesus’ teaching that people should sell everything they have and give their money to the poor, but he says Flavius couldn’t have had the life that he’s had if Marcus had followed that teaching; in reply, Flavius walks out on his father and says he wants nothing to do with his father’s money.

Fourth, there is an interesting tension in the scene where Marcus watches the crowd from a short distance as Jesus carries his cross. The follower of Jesus who spoke to Marcus in the earlier scenes appears here too, bemoaning the fact that Jesus is about to die, and he urges Marcus to intervene — but Marcus, who briefly thinks about using his sword in defense of Jesus, decides he has to follow the horses carrying his bags of gold instead. The Jesus follower than shouts at Marcus, “When your world crumbles around you, you will understand what you have done today! You have rejected him!” On the one hand, this scene fits the film’s overarching theme regarding the conflict between material and spiritual wealth: Marcus, by following his gold instead of Jesus, chooses money over God. And yet, the film suggests that following Jesus, for Marcus, would have meant intervening violently on Jesus’ behalf — and hadn’t the Jesus of the Bible already told Peter not to defend him with a sword by this point?

Then there is the film’s portrayal of Pilate. On the one hand, the film follows the traditional and somewhat unhistorical portrayal of Pilate as a conscientious man who is forced to execute Jesus against his better judgment.4 (The crowd calling for Jesus’ death is much bigger than the crowd that follows Jesus when he heals Flavius.) But in his scenes with Marcus, Pilate is more of a political schemer who uses Marcus to get back at Herod (by encouraging Marcus to steal horses and gold from an Ammonite chief who is allied with Herod), and he even considers profiting personally from Marcus’s actions. This fits the bit in Luke’s gospel which says that Herod and Pilate were enemies prior to the crucifixion of Jesus; however, it is not clear whether the film’s timeline would allow for Pilate to send Jesus to Herod, also as per Luke’s gospel. The film’s most explicit nod to the gospels comes when Pilate washes his hands and says that he is innocent of Jesus’ blood, as per Matthew’s gospel. Finally, when Pilate appears in Pompeii and is confronted by Flavius’s idealism many years later, he asks “What is truth?” just as he did when faced with Jesus in John’s gospel.

The Last Days of Pompeii isn’t a great film by any stretch — it’s a fairly typical mid-1930s melodrama — but it’s interesting, both as a time capsule that captures common attitudes about wealth and poverty at the height of the Great Depression, and also as one of the very rare films made during this period that depicts, however tangentially, a few key events from the Bible. There’s a certain look and sound that the Hollywood films of this era had, when sound was new and actors spoke with certain kinds of accents, and this may be the only film that gives us even a taste of what it would have been like to see a Bible story filtered through that aesthetic. As such, it’s worth a look, for those who are curious about such things.

–

Two clips from the film can be streamed via the Turner Classic Movies website.

Below are some screen captures from the film, which is available on DVD.

The opening title card notes that the film is not based on the identically-titled Bulwer-Lytton novel:

The first shot in the film is a finely-executed matte shot of a boat sailing near Pompeii:

Our first look at Marcus the blacksmith:

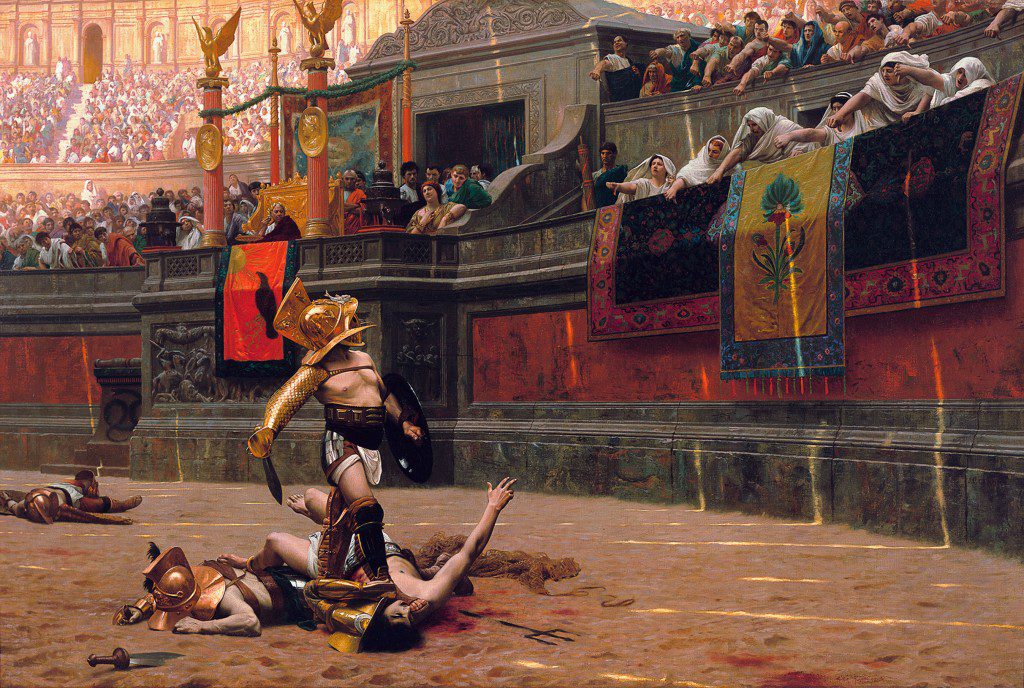

Marcus becomes a gladiator…

…in a shot that echoes Jean-Léon Gérôme’s 1872 painting Pollice Verso:

A fortune-teller predicts that Flavius will meet the “greatest man” in Judea:

Marcus meets a follower of Jesus in a stable:

An establishing shot of Jerusalem:

Pilate complains to an assistant about Herod and the Ammonites:

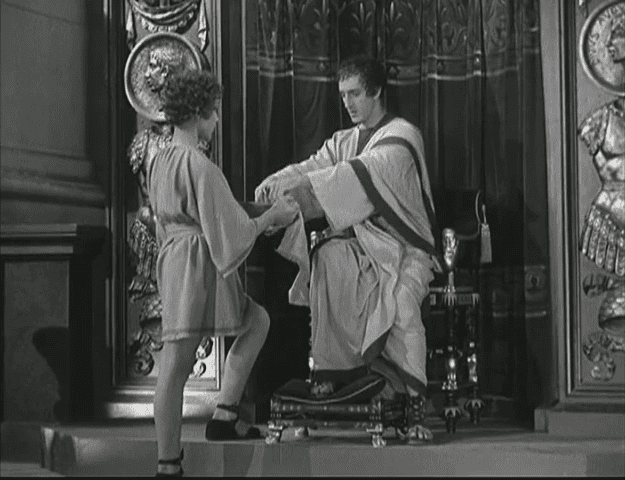

Pilate stays seated as he talks to Marcus:

Marcus approaches the crowd surrounding Jesus:

A light shines on Marcus’s face as he asks Jesus to heal Flavius:

A crowd calls loudly for Jesus’ execution:

Pilate washes his hands and says he is innocent of Jesus’ blood:

Marcus watches as Jesus carries his cross through the streets of Jerusalem:

Marcus leaves Jerusalem while Jesus is crucified in the background:

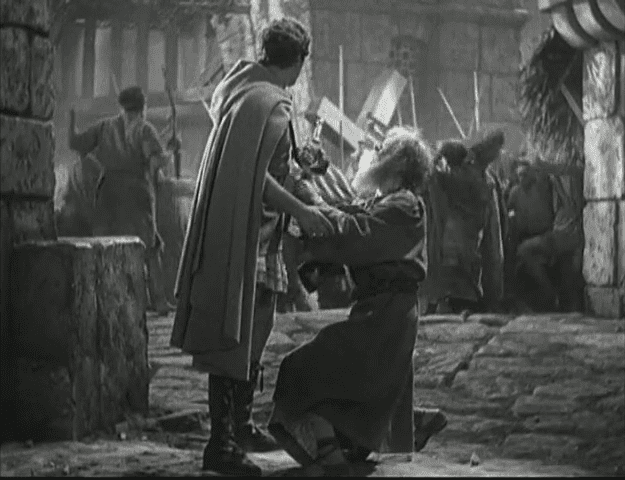

Pilate visits Marcus and Flavius in Pompeii:

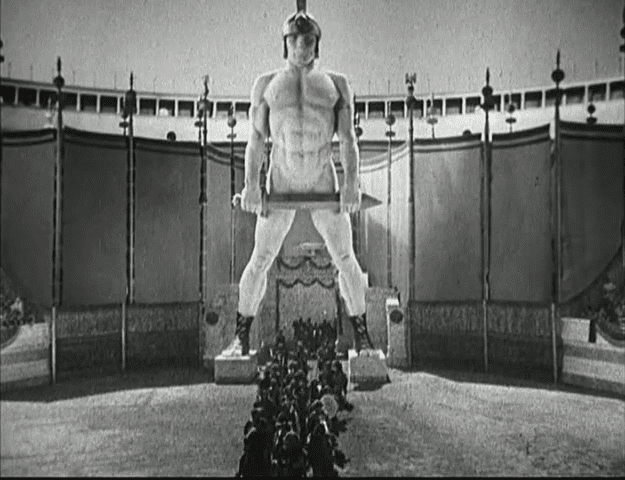

The statue at the entrance to the arena in Pompeii:

The volcano erupts:

Marcus has a vision of Jesus as he lays dying amidst the rubble:

–

1. For the purposes of this discussion, “the 1950s” basically begins with 1949’s Samson and Delilah.

2. I refer here to films that present the biblical narrative in its historical setting. I am not thinking of films like, say, The Green Pastures (1936), which re-imagined several biblical stories as quasi-modern folk tales. There were also foreign and independent Bible films produced during this period — such as Julien Duvivier’s Golgotha (1935), the British short-film series The Life of St. Paul (1938) and the experimental film Lot in Sodom (1933) — but those were all produced well outside the Hollywood mainstream.

3. This was not Rathbone’s only Bible movie; he also played Caiaphas in Pontius Pilate (1962).

4. Both the gospels and secular history agree that Pilate was a brutal, provocative leader who cared little for keeping the peace, except insofar as turmoil would get him in trouble with the Emperor.