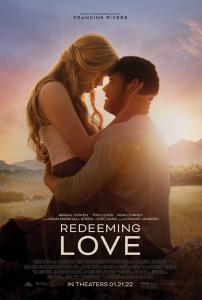

Has any “faith-based” film ever advertised itself with a sex scene before? I doubt it, but that’s basically what Redeeming Love does: the poster shows Angel (Abigail Cowen), a former prostitute, straddling her husband Michael (Tom Lewis) in the great outdoors while he places his arms around her waist, and while the characters do have their clothes on, anyone who has seen the film knows exactly what they’re doing in that moment. To the uninitiated, the image may be an innocent romantic come-on; but to those who know the movie – repeat viewers, perhaps – that image will always mean something more.

I have not read the 1991 novel on which this movie is based, but author Francine Rivers co-wrote the screenplay with director D.J. Caruso (Eagle Eye, xXx: Return of Xander Cage), and she has been actively involved in promoting the film, so I assume the film focuses on sex as much as it does at least partly because the fans expect it. Either way, it’s interesting how the film dwells on that, because it suggests a thirst for Song of Songs-style eroticism even in a story like this, which is based on a biblical text that is partly about the taming of sexual desire.

I have not read the 1991 novel on which this movie is based, but author Francine Rivers co-wrote the screenplay with director D.J. Caruso (Eagle Eye, xXx: Return of Xander Cage), and she has been actively involved in promoting the film, so I assume the film focuses on sex as much as it does at least partly because the fans expect it. Either way, it’s interesting how the film dwells on that, because it suggests a thirst for Song of Songs-style eroticism even in a story like this, which is based on a biblical text that is partly about the taming of sexual desire.

Redeeming Love, which is set in California during the 1850s Gold Rush, is the latest in a recent flurry of movies that are based on the Book of Hosea but move it to a modern (or, in this movie’s case, almost-modern) setting. The biblical story is about a prophet who marries a promiscuous woman and holds up their marriage as a symbol of God’s relationship with Israel: the nation is unfaithful and deserves to be punished, but God, despite his feelings of betrayal, is determined to take the nation back, even at great cost to himself (Hosea buys his wife back from slavery at one point). As I pointed out a few days ago, most films have ditched the prophetic-message symbolism and have focused on the marriage itself, and in doing so they have humanized both Hosea and his wife – making him more open to criticism, and making her more sympathetic. In these films, we are not asked to condemn Hosea’s wife but to understand her and the traumatic past that has brought her to this point.

Redeeming Love certainly follows the template insofar as creating sympathy for the wife is concerned; it adds more trauma to her back-story than all the other films combined. Angel (birth name Sarah, played as a child by Livi Birch) is the daughter of an unwed mother (Nina Dobrev) who, like Fantine in Les Miserables, ends up turning to prostitution to make ends meet – and when she dies, there is no one to save Angel from a similar fate the way Jean Valjean saved Cosette. Instead, Angel is sold into prostitution – she even witnesses the murder of the person who sold her – and she goes on to suffer rape, incest, forced abortion, and various other indignities before a man named Michael Hosea comes into her life and tells her, at their very first meeting, that he is going to marry her.

But if the film gives us extra reasons to see things from Angel’s point of view, it turns Michael – the Hosea figure – into an almost impenetrably perfect paragon of virtue. Maybe this is because Michael, like Hosea, is supposed to represent God himself. Or maybe it’s because Redeeming Love is, at heart, a fantasy about the perfect man coming into a woman’s life and slowly, patiently allowing her to resolve all of her problems.

Either way, it is very difficult to take Michael seriously as a person, because he just doesn’t have the interior life that Angel does. Early on, Michael asks God to give him a wife – someone to share his new farm with – and in his next scene, he sees Angel walking down the street with her bodyguard, and his instant smittenness isn’t affected one bit when someone informs him that that woman over there is a prostitute. “Lord, you most certainly have a sense of humour,” says Michael, and there is no indication whatsoever as to why Michael believes that that woman must be the one for him. Later scenes do show Michael wrestling with his emotions and asking God for the strength to hold back and let Angel make the right choices, but these scenes play like Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane; they don’t undermine the impression one gets that the character is fundamentally perfect.

Perhaps no scene sums up how differently Angel and Michael are developed in this film better than the one in which Angel says, “I’ve got too many demons,” and Michael replies, “My father was my demon.” He then goes on to explain that his father was a plantation owner who punished Michael for saying he was going to free the slaves some day. Angel’s “demons” are internal, but Michael’s, as far as we can tell, are external, and that’s that.

I hasten to add that Cowen and Lewis, the actors who play Angel and Michael, do what they can with the material. I was particularly impressed by the way Cowen balances Angel’s feelings of helplessness with her efforts to assert her sexual power even as that power is trapping her in a life she doesn’t want. Some critics have complained that Angel has very little agency, but I disagree; I think the film is quite clear that Angel is trying to find her agency but is constantly hemmed in by circumstance – by poverty, by thieves, by exploitative pimps and madams – and when Michael comes into her life and changes those circumstances, she responds the only way she knows how, by running away. As for Michael, well, Lewis plays him with all the sincerity he can muster, and his passion for Angel is certainly there. You feel for him, at least, when Angel’s actions hurt him.

Unlike the other Hosea movies, which portray religion itself as one of the things that can push their female protagonists away, Redeeming Love puts religion squarely on the side of the good. Michael has a Bible and prays in an empty church (admittedly, we never see him in any sort of religious community), while Angel’s narrative arc – including her rejection of God as a child and her ultimate embrace of him as an adult – is framed by images of her tossing and then reaching for her mother’s crucifix necklace. Angel and Michael are even visited by a family who represent “purity” to Angel, one of whom sings a folk song about Bible stories around a camp fire. In contrast, the primary villain of the story is a human trafficker who pursues Angel relentlessly – burning down her new places of employment like the serial arsonists in a Lemony Snicket novel – and is ultimately called a “father of lies”, which is a classic biblical name for the Devil (cf John 8:44).

There is a lot more that could be said about this film and how it plays with social, cultural, and historical expectations. On multiple occasions, Angel objects to the idea that marriage has made her some sort of “slave” to Michael, which he insists isn’t true, but this story actually takes place at a time when slavery still existed in the United States, and the film doesn’t really do much with that subtext (the story about Michael’s father aside). At one point, a black man helps some girls escape from a child sex trafficker, and the sex trafficker, who is white, is promptly lynched by a mob. (Would mobs back then have been so offended by the thought of sex with young girls? The age of consent in most states by the late 19th century was between 10 and 12 – and in Delaware it was as low as 7.)

And then there is the film’s approach to sex. At the visual level, Redeeming Love pushes the boundaries of PG-13 filmmaking and “faith-based” filmmaking alike, with contrived blocking that shields things from the eye even as it teases the imagination. (At one point, Michael even places his hand on Angel’s naked breast to hide it from the camera, which is worlds away from, say, Kirk Cameron’s refusal to even kiss actresses who are not his wife.) At the same time, however, the film pulls the interesting trick of saving the friskiest scenes for the marital sex, while keeping the prostitution out of frame. This is a striking departure from other movies that revel in adultery while keeping the husband-and-wife stuff tame if not downright boring (think, for example, of Ryan’s Daughter).

I can appreciate that the filmmakers needed to deal with the extreme sexual behaviour described in the Bible, which is something that earlier films like Oversold and Amazing Love haven’t really done. (People might spread rumours about the Hosea figure’s wife in those films, but we only ever see her with one other man in each film.) I can also appreciate that there may be a need, in a story like this, to redeem not just the individual person but the act of sex itself, and to centre both the story and the sexual experience in a female perspective, both of which are things the biblical story doesn’t do.

But if you’re going to ditch the prophetic message that is the Book of Hosea’s point, then at the very least I’d like to see some realistic human behaviour; if you’re going to tell a story about a man who dedicates his life to a complete stranger’s sexual salvation, you have to give me some sense of who he is and why he’s doing what he does. It takes two to tango, after all, and if I’m going to believe in a relationship, I need to believe in both partners as people. Instead, what we get feels like mere wish fulfillment.

–

Meanwhile, a few extra notes, organized like the notes in my last post:

Whose story is it? This is definitely Angel’s story, though it crucially ends with an image of family unity, which none of the other Hosea films I’ve looked at did.

Incidentally, just about everything in this story seems to revolve around Angel: there’s the villain who pursues her from town to town even though he must have many other sex slaves to manage; there are the brothel clients who buy lottery tickets to be with her (and specifically her!) for just a few minutes, which suggests she must be very good at her job despite her constant efforts to get out of it; there is the pure-hearted, infinitely-patient man who pops up out of the blue to take her away from all that for no discernible reason; and finally, the film even ends with a hint that something miraculous has taken place.

Children. Michael wants children but Angel has a secret: an abortion forced on her by the man who “owned” her has left her infertile. The last time she leaves Michael, it is not to return to a life of prostitution but to give Michael an opportunity to marry someone else who can give him children. In the end, Angel and Michael are reconciled and, it seems, they do have a child, possibly miraculously.

The other man (or men). In Oversold, the main rival for Sophi’s affections was Josh’s stepbrother; in Hosea, one of Cate’s former clients was a business partner of Henry’s. In Redeeming Love, one of the men Angel sleeps with after she marries Michael is Michael’s brother-in-law Paul, who was married to Michael’s now-dead sister.

Interestingly, unlike the other two films, which cast the “other men” as one-dimensional villains, Redeeming Love offers redemption for Paul just as much as it does for Angel. Before Angel sleeps with Paul, Michael tells him to go to church and “try to remember the man you were when you married my sister.” And afterwards, Paul ends up marrying another woman and apologizing to Angel for the way he treated her.

Also interesting: when Angel hears who Paul married, she protests that the woman in question was “pure” and thus not right for Paul – and so Angel has to learn to see past Paul’s lack of “purity”, just as Paul has had to learn to see past Angel’s own lack of same.

However, while Redeeming Love does go further than any of the other films in redeeming one of the female protagonist’s sexual partners, it also goes further than any of them in punishing some of the men who are responsible for her life in prostitution. Her father shoots himself in the head after he realizes he has slept with his own daughter, and the sex trafficker who pursues her and haunts her dreams is ultimately lynched by a mob.

Debt repayment. Recent films like Oversold, Amazing Love, and Hosea have all made a point of emphasizing the incredible cost to the Hosea figure personally when he pays his wife’s debts; in one film, he pays it with his inheritance and the proceeds of the sale of his house, and in another, he pays it by selling his stake in a business that he has spent years building up. These payments are all presented as the climaxes to their stories.

Redeeming Love, on the other hand, has almost zero interest in the cost of Angel’s financial debts. The financial debt matters to Angel, yes, but Michael pays it without batting an eye, the day he marries her and takes her out of the brothel. The real cost of the relationship to him throughout the film is an emotional one. (And the fact that he isn’t hurt financially allows the film to have a happier, more wish-fulfilling end than the other films.)

Christianity. See the main review above.

Other Bible passages. Angel’s mother dies while saying the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:9-13). Someone sings a folk song – ‘Dry Bones’, first recorded in 1928 but possibly much older – that references the life of Enoch (Genesis 5:21-24) and God’s appearance to Moses at the burning bush (Exodus 3-4:17).

Curiously, while Michael Hosea owns a Bible and thus owns a copy of the Book of Hosea, he never comments on the parallel between himself and his namesake.

The film also opens with a quote attributed to Shakespeare (“All that glitters is not gold”; the actual word in The Merchant of Venice, Act II Scene 7, is “glisters”), and there is a scene in which Angel’s mother teaches her to read with a passage from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

Sex. See the main review above.

Troubled homes. Angel’s mother was a married man’s mistress, and the man beat her for, among other things, keeping Angel instead of getting an abortion. Michael’s father beat him for wanting to free the slaves, and made him live with the slaves. The fact that they both had bad childhoods gives Michael a reason to tell Angel, “Sometimes you have to leave behind what you were born into to become who God meant you to be.”

Self-harm. Angel does not deliberately harm herself, but she does say she “chose to die”.

Connections with other Hosea movies. A human trafficker called The Duke is clearly associated with the Devil when someone calls him a “father of lies” (cf John 8:44). This parallels the depiction of Ethan in Oversold; at one point he dresses in red and looks out over Las Vegas and says “I own this town,” which, as Matt Page has noted, evokes the way Satan claimed jurisdiction over the kingdoms of this world when he tempted Jesus.

Angel prays to God for the first time when she’s in desperate need of help at the climax of the movie, after she has left Michael and found herself in The Duke’s clutches again. This parallels how Sophi prays to God for the first time at the climax of Oversold, after she has left Pastor Josh and she finds herself in Ethan’s clutches again.

The last time Angel runs away, Michael insists that he cannot “go after her”, as much as he wants to, because “she has free will. It has to be her choice” to come back. This parallels how Henry leaves two notes for Cate in the hospital in Hosea, one for if she decides to come back to their home, and the other for if she decides not to come back.

Angel tells Michael, “I’m so sorry for the pain that I’ve caused you,” and Michael says, “It’s the pain that brought us to this moment.” This parallels the bit in The Green Pastures where Hezdrel says God and men can both find mercy through suffering.