There’s been a flurry of Hosea movies in the last few years.

For most of the history of film, there has been very little cinematic interest in the biblical prophet who married a prostitute; it’s difficult to come up with more than a few films from the first century of filmmaking that have even mentioned the story.

But over the past decade and a half, there have been at least four attempts to dramatize the story, albeit usually in a modern (or almost-modern) setting.

The newest of these films – Redeeming Love, which sets the story in mid-19th century California – is coming to theatres this Friday. And in anticipation of the film’s release, I’m going to be looking at some of the other films that have tackled this story.

Today’s post covers four films from the 20th century – only one of which appears to have been an actual dramatization of the biblical story.

–

Matinee Theater: The Prophet Hosea (1958)

I say “appears to” because I have not yet been able to find the film in question, which was actually an episode of Matinee Theater on NBC.

Wikipedia says the series was “usually broadcast live”, so there would be no original film print that one could turn to – and it seems doubtful that this was one of the “later episodes” that were “preserved on color film for later rerun syndication”.

In any case, without actually seeing the episode, it is interesting to read what little bits of information about it are out there. For starters, consider this IMDb summary, which appears to be taken from the official description in the TV guides of the time:

Story of the Hebrew prophet, his wife Gomer and the unethical priest Dagnon. Gomer leaves her husband for the love of Dagnon, who is eventually won over by Hosea’s ethical precepts and deserts Gomer.

This summary raises all sorts of questions.

For example, who is the audience supposed to sympathize with in this version of the story? Most recent films have put the Hosea and Gomer figures on equal footing or have even privileged Gomer’s point of view. But this description makes it sound like Gomer gets left behind in a story about two men who come to share the same beliefs.

Consider also how Matinee Theater was launched by the network to “bring a new dignity” to the kind of shows that were aimed at suburban housewives of the period.

As Matthew Murray explains in an essay in Small Screens, Big Ideas: Television in the 1950s, Matinee Theater – which had an unusually large budget and was broadcast in colour, a rarity in the 1950s – was basically competing with daytime soap operas, which were aimed at an audience of women who had time off from their husbands and children and thus, it was believed, were inclined to engage in fantasies that strayed from what was considered “acceptable” for women in that time and place.

That is the context in which the 20th century’s only dramatic adaptation of the Hosea and Gomer story was produced. It is in that context – a network juggling a bid for prestige with the demands of the daytime audience – that the series turned to a story from Holy Scripture about a woman who leaves her husband for another man.

Murray’s essay does not say much about the Hosea episode itself. It does tell us that the show’s executive producer, Albert McCleery, took the series in an increasingly less “dignified” direction and said at one point, “Sex is all a woman thinks about while she’s sitting at home and we can give it to her!” It also mentions the Hosea episode briefly in a passage that sums up viewers’ reactions to the show’s more provocative elements:

In letters to the network, some viewers resented what they perceived as a devaluation of Matinee Theater’s cultural superiority, contesting the appropriateness of the changes in content and presentational form. For undermining ‘what sense of decency and respect for virginity there is left in the world’, a Rochester woman protested the series’ tendency to ‘concentrate on the unwed mother problem’. A New Yorker complained that ‘Matinee performances of the last few weeks’ had exhibited ‘low moral standards’, to the point of being ‘positively disgusting’ at times. The Los Angeles Jewish Community Council found The Prophet Hosea to be a ‘sexational melodrama’, where ‘his wife’s nymphomania is exaggerated’.

And that sums up about all I’ve been able to learn about the episode so far. A few notes on the cast and crew, though:

- The episode was written by Marjorie Duhan Adler, whose other scripts for Matinee Theater included 1957’s ‘The Story of Sarah’, a dramatization of the Abraham and Sarah story that aired just before Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year.

- Hosea was played by Joseph Wiseman, who went on to play the titular bad guy in the first James Bond film, 1962’s Dr. No. Wiseman’s other biblical roles include Mijamin in 1954’s The Silver Chalice, Carmish in 1955’s The Prodigal, and Pharaoh in 1966’s Great Bible Adventures: Seven Rich Years and Seven Lean – and, while this wasn’t a biblical production per se, he also played an Essene in 1981’s Masada.

- Gomer’s lover Dagnon was played by Robert Loggia, whose other biblical roles include Joseph in 1965’s The Greatest Story Ever Told and the title role in 2012’s The Apostle Peter and the Last Supper.

- Gomer was played by Roberta Haynes, whose final IMDb credit is ‘Mary the Mother’ in The Copper Scroll of Mary Magdalene, which was filmed in 1972 but the director – Mars Needs Women’s Larry Buchanan – was still editing it when he died in 2004.

–

Moving on to other things, there are three other films from the 20th century that allude to the story of Hosea even if they don’t quite depict it directly.

–

The Green Pastures (dir. Marc Connelly & William Keighley, 1936)

The Green Pastures is unique among Hollywood films for telling a series of Bible stories with an entirely African-American cast.

The stories, framed as a series of Sunday school lessons taught to children, are told in a folksy idiom, and the cultural archetypes and stereotypes involved are problematic enough by today’s standards that the DVD comes with a disclaimer.

Be that as it may, one of the interesting things about the film is its theology. God – or, as the dialogue calls him, “De Lawd” (played by Rex Ingram) – is a self-described “God of wrath and vengeance” who punishes his creations for their sins and is increasingly disheartened that nothing seems to get them to stop: not floods, not thunderbolts, not slavery. Nothing seems to convince them to stop their wicked, wicked ways.

Then De Lawd encounters a man named Hezdrel (also played by Ingram), who doesn’t recognize him at first, and he learns that the Hebrews are now worshiping “a new God” of mercy whose message is being preached by someone called Hosea:

Hezdrel: Oh, you talkin’ about that old God of wrath? We’s got a new God now.

De Lawd: Who said so?

Hezdrel: Our preacher, old mister Hosea.

De Lawd: But you know there’s only one God, ain’t they?

Hezdrel: Maybe there is. Maybe we just got tired of his appearance that old way.

De Lawd: What do you mean?

Hezdrel: I mean that old God that walked the earth in the shape of a man. I guess he lived with man so much ’til all he could see was the sins of man. That’s what made him a God of wrath. Of course they is the same God. He just ain’t fearsome no more. Now he’s a God of mercy!

De Lawd: Mercy? How did you humans find out about mercy?

Hezdrel: The only way we could find it. The only way anyone can find it.

De Lawd: How is that?

Hezdrel: Through suffering.

De Lawd: So that’s what faith is. Thank you, Hezdrel.

Hezdrel: For what?

De Lawd: Teaching me something. I guess I’ve been so far away I was just way behind the times.

De Lawd then returns to Heaven and ruminates on what Hezdrel said about finding mercy through suffering. “Did he mean that even God must suffer?” And then De Lawd looks into the distance and sees a man carrying a cross…

There’s a lot to unpack here and it’s obvious that none of this can be taken in a strictly literal way. (Even if we posit that there is only one God and he is capable of change, how is it that the God of mercy is being preached before he even exists? What’s the chain of cause and effect here? Is it significant that Hezdrel – the human who “enlightens” God – is the only human who is played by the same actor as God and is thus, in a sense, more “in his image” than any of the other humans we see? And what exactly is the relationship between the God we see in Heaven and the man carrying his cross? Etc., etc.)

It’s also worth noting that we never see Hosea himself here, nor are there any references to his wife Gomer or to any of the details of their story.

Instead, Hosea is simply cited as the one who has been preaching a God of mercy. And indeed, the biblical Hosea does say that God “desires mercy, not sacrifice” (Hosea 6:6) – a line that is quoted by Jesus himself when the legalists of his day ask him why he associates himself with “sinners” (Matthew 9:13, 12:7).

–

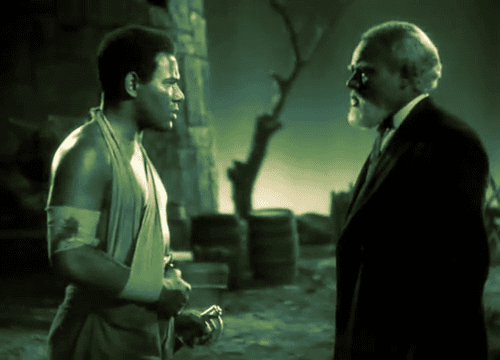

Walk on the Wild Side (dir. Edward Dmytryk, 1962)

Walk on the Wild Side is the one film I’m highlighting today that isn’t based directly on the Bible in any way, shape, or form. It’s a thoroughly modern story, set in the 1930s, about a man named Dove Linkhorn (Laurence Harvey) who goes looking for a former lover named Hallie (Capucine), only to discover that she’s working in a brothel.

The film plays with religious impulses but channels them in the direction of romance. Early on, when someone asks Dove what his religion is, he says it’s Hallie – and his devotion to Hallie is so pure, and his resistance to other women so complete, that one of those women calls him a “Bible thumper”. But when Dove encounters an actual fundamentalist – a self-ordained street preacher who wags his finger at Hallie and calls her a “hip-slinging daughter of Satan” – Dove takes a stand against him:

Dove: You’re no friend of God or man, standing there hollering hate to the world. God is love. God is mercy and forgiveness. Try preaching that sometime, mister preacher. Teach people to forgive, not to crawl in fear. Teach people to love, not hate! Preach the Good Book! Preach the truth!

It bears mentioning that Dove does not yet know at this point in the story that Hallie has become a prostitute; he does not yet know that there is something to forgive. He is certainly defending Hallie from the finger-wagging, but he is also responding as a matter of general principle, and he has yet to put his own mercy to the test.

When Dove does learn what Hallie does for a living, it rattles him at first. He is proud, and he is quite sensitive to the shame associated with certain gender roles. (In an earlier scene, when a woman offers to give him a job and maybe let him live with her, he replies, “You know what they call a man who lives off a woman?”) But he quickly rebounds, and he cites the story of Hosea and Gomer by way of explanation:

Dove: In the Bible, Hosea fell in love with Gomer. She was a harlot. They got married, and she couldn’t stay away from men. Hosea got mad and threw her out, and sold her into slavery. But he couldn’t get her out of his mind so he went looking for her. When he found her, he brought her back home, but it was no good. Before long, she was up to her old tricks again. But he loved her anyway, and he couldn’t give her up. So he took her into the wilderness, away from temptation, away from other men. And that’s what I have to do with Hallie.

Suffice it to say that there’s a fair bit of simplification, even projection, here.

The Bible itself never quite ascribes to Hosea himself the emotions that Dove describes – Hosea doesn’t marry Gomer because he “fell in love” with her or felt any sympathy for her, but because God told him to hold her up as a symbol of Israel’s faithlessness (Hosea 1:2) – but the Bible does suggest that God himself felt those emotions, as he wavered between punishing Israel for its idolatry and winning the nation back.

Likewise, the Bible never says that Hosea himself took Gomer out into the wilderness. Instead, this is something God talks about doing, symbolically, as a way of rekindling his relationship with Israel, by taking it back to its post-Exodus roots (Hosea 2:14-15).

Also, the biblical Hosea does not sell Gomer into slavery; instead, the recurring theme in Hosea is that Gomer and the nation she represents have repeatedly sold themselves into prostitution, and Hosea buys Gomer back from one of her lovers (Hosea 3:2).

Another, smaller nit-pick: the sequence of events in Dove’s monologue is also at odds with the biblical text. Dove talks about Gomer’s slavery, then says Gomer was “up to her old tricks” again, and then says Hosea took Gomer into the wilderness. But in the text, the wilderness and the slavery are mentioned in the opposite order, and there is no sense that Gomer went back to “her old tricks” after Hosea bought her back. Instead, the rest of the book of Hosea is a series of prophetic statements denouncing Israel for its sins and pointing beyond those denunciations to the hope that Israel will be restored.

A few quick points about the cast before we move on to the next film:

- The woman who runs the bordello is played by Barbara Stanwyck, in one of her very last roles for the big screen, though she continued to work on television until the mid-1980s.

- Anne Baxter plays a Mexican widow who runs a café. This was just six years after she played Nefertiri in 1956’s The Ten Commandments, and she worked mostly in television after this, too.

- Jane Fonda, who was 24 when the film came out, plays an underaged orphan who gets a job at the brothel. It was her second film.

Also, curiously, this film takes place in and around New Orleans primarily, just like The Green Pastures did a quarter-century earlier. Just a coincidence, I’m sure.

–

The Milky Way (dir. Luis Buñuel, 1969)

Finally, one of the most interesting films by the Spanish surrealist Luis Buñuel is this look at Catholic history and theology, which happens to be bookended by nods to Hosea.

The Milky Way takes its title from one of the nicknames for the Camino de Santiago, a network of pilgrimage trails that leads to the supposed burial place of St. James in northern Spain. The film follows two vagabonds who take the trail and find themselves moving back and forth through time and witnessing various controversies.

At the very beginning of the film, the two vagabonds encounter a man who tells them, among other things, “Go, take a whore for a wife. And bear children of that whore. Name the first, ‘Ye are not my people,’ and the second, ‘No more mercy.’”

This dialogue is a compressed version of Hosea 1. The biblical Hosea actually had three children, one of whom was named after Jezreel, the city where a general named Jehu staged a coup, made himself king, and began slaughtering every member of the previous royal family. While the coup was instigated by the prophets Elijah and Elisha (I Kings 19:16-17, II Kings 9-10), the prophet Hosea seems to condemn it (Hosea 1:4-5).

This will be a recurring theme in Hosea movies: a tendency to downplay the prophetic message to Israel, even though that was the central point of Hosea.

Most films prefer to focus on the personal or psychological aspects of the Hosea-Gomer relationship. But Buñuel downplays the nation-specific parts of the text because he’s looking at the history of Catholicism (including its scriptures), and he’s playing up some of the aspects of that history that may seem more absurd to modern viewers – like a God who tells people to have symbolic relationships with prostitutes.

Anyway. At the end of the film, the two vagabonds reach the outskirts of Santiago, where they meet a prostitute who complains that there are no pilgrims any more, not since people discovered the bones of St. James actually belonged to someone else, and thus there are no more clients for her services. She then takes the vagabonds with her into the woods, and she tells them she wants a child – and she says she would call one vagabond’s child ‘Ye are not my people’ and the other vagabond’s child ‘No more mercy’.

And so the prophet’s condemnation of Israel becomes, if anything, a comment on the Church and its waning hold on the public and its beliefs.

This scene also subverts the Hosea motif in two interesting ways: First, the prostitute is planning to have the symbolically-named children by two different men and not as part of a monogamous relationship. And second, it is the prostitute, not the men, who names the children. It is as though Gomer, not Hosea, were God’s prophet and spoke with his voice – which is not just a reversal of gender roles but also turns the Gomer figure into a kind of religious prostitute, which the biblical Hosea preached against (Hosea 4:14).

–

And that wraps up my quick look at Hosea references in 20th-century film. Over the next four days I’ll be looking at 21st-century films, culminating in Redeeming Love.

— The image at the top of this post is from Walk on the Wild Side (1962).