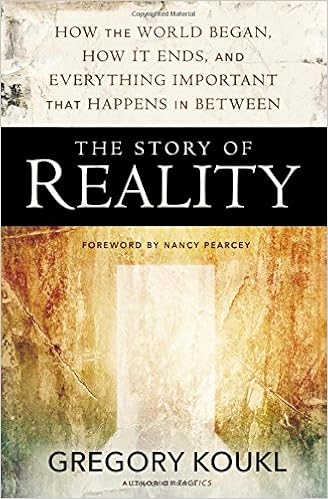

Greg Koukl has come out with a new book entitled The Story of Reality: How the World Began, How It Ends, and Everything Important that Happens in Between.

How’s that for an all-inclusive title?

I caught up with Greg recently to discuss his new book.

Enjoy!

Instead of asking, “What is your book about?” I’m going to ask the question that’s behind that question. And that unspoken question is, “How are readers going to benefit from reading your book?”

Greg Koukl: That depends on the reader.

After Christians finish The Story of Reality, I want them to say, “Wow. I never knew how all the pieces of the Christian puzzle fit together so perfectly from beginning to end. I never knew how much common sense it all makes. Why hasn’t anyone ever told me this before?” And that’s exactly what many have actually said to me once they read Reality.

Many followers of Jesus—some new to Christianity and some who have been around a while but have been lost in the details—have never seen the big picture. I wanted to put the pieces together in a connected, coherent way so they could clearly see how the drama of the Christian Story unfolds step-by-step and how it make perfect sense of the world we actually live in. As a result, I think they’ll be deeply encouraged, convinced that the Christian Story is actually what Francis Schaeffer used to call “true truth.” It’s true to the way the world actually is and isn’t just a religious fairytale. We aren’t just wishing on a star when we put our trust in Christ.

For non-Christians I have a different goal. I want to surprise them a bit and also annoy them a little, in a good way. Every time I sat down to wordsmith the text I was thinking about the person who’d never given Christianity any serious thought, maybe because he simply did not think Jesus was worth thinking about or hadn’t heard the Story in a way that made sense to him. I wanted to show that person a different side, that our Story had a deep internal logic to it and that it also made sense of some of the most obvious—and most important—features of the world, like the problem of evil or unique human value. I wanted that person to walk away from the book intrigued, challenged, even irritated because they couldn’t simply dismiss Christianity as easily as they used to. I wanted to put a stone in their shoe, so to speak, but do that with ordinary, non-theological language he could understand without feeling patronized or looked down upon.

What motivated you to write this book?

Greg Koukl: Two things have been bothering me for a long time. The first is the tendency of people in general—and that includes Christians—to “relativize” religion. Any religious belief is only “true for,” so to speak—true for you or true for me or true for those people on the other side of the world. It’s “true” only in the sense that some people believe it. That’s all. Generally, people don’t think religion can be true in the sense that, say, gravity is true. Instead, they think of religious stories as make-believe-to-make-me-feel-happy kinds of stories.

But Jesus didn’t see the religion project that way. To Him, religion wasn’t first about what was going on in the inside—a personal relationship with God or a private religious belief or an individual ethical viewpoint. Instead, Jesus understood religion first as a description of what the world was like on the outside—the world “out there” as it really is. It wasn’t a story about mere “belief.” It was a story about reality. I wanted people to be crystal-clear on the kind of claim the Bible was making, even if they didn’t take that claim seriously at the moment. That’s the first thing that motivated me.

Second, I’ve been bothered by how poorly believers understand their own Story. They have bits and pieces, of course, but they’re missing enough that they can easily become prey to ideas that sound spiritual, but end up being foolishness in the end. They are “tossed here and there by waves and carried about by every wind of doctrine,” as Paul put it.

I wanted to help those Christians out by clearly laying down the foundation pieces of Christianity, the essential building blocks that make our Story different from every other religious story and without which would not be real Christianity anymore (what C.S. Lewis called “mere Christianity”), but either a counterfeit of Christianity, like Mormonism, or a different religion altogether.

What is a worldview, exactly?

Greg Koukl: Some people suggest that a worldview is like a set of glasses that color the way you see the world around you. A Christian interprets the world one way, and an atheist interprets the same world a completely different way since he’s looking through different worldview “glasses.”

I think that metaphor is helpful, but I prefer a different one. I like to think of a worldview as a sort of map of reality. A physical map (or GPS image) tells us what the physical terrain is like so we can get where we want to go. If it’s a good map—if it’s an accurate description of the lay of the land—then we’re able to navigate accurately. We drive and we arrive.

In a similar way, a worldview is like a map of the entire world—and here I mean all of reality, not just the planet. It describes what is real and what isn’t, where we came from, why we’re here, what—if anything—is good, true, or beautiful, and if anything ultimately matters in the long run. Everybody has a rough idea of some of the answers to these questions, and as we encounter new details of our world we fill in more of the spaces. When we discover details that don’t seem to fit with our view of the world, we have a kind of “crisis of faith,” even if our worldview is not especially religious. We’re forced to redraw our “map” a bit. I’m hoping that The Story of Reality will fill in more details for the Christian believer and will create a crisis of faith for the nonbeliever.

Why is it important for Christians to embrace the worldview you’re presenting in the book?

Greg Koukl: It’s the same reason any reader, Christian or otherwise, should embrace the worldview presented in this book: because it’s true. Reality has a way of injuring people who don’t take it seriously. If you don’t believe in gravity, for example, and then step off a tall building, you won’t just float away.

Jesus is a person to be reckoned with, not trifled with. Ideas have consequences, and the things Jesus talked about have the greatest consequences of all. If the Christian doesn’t get reality right, he loses effectiveness in this life. If the non-Christian doesn’t get reality right, he loses much in this life, and everything and the next one. As Jesus put it, “What does it profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses his soul?”

How is the Christian Story different from the other stories that people and religions tell?

Greg Koukl:There are three things that make the Christian Story significantly different from all the rest.

First, in our Story man does not rescue himself for his own glory. Instead, God rescues man for His glory. Every other story describes what man needs to do to fix himself and save him from whatever else is wrong with the world. In our Story man is a helpless slave—enslaved to his own passions, the flesh, and enslaved to a cruel master, the devil—a slave who God Himself rescues and adopts into His own family. It is the very worst news coupled with the very best news.

Second, the details of our Story and the details of reality, as far as we’re able to measure them, fit perfectly. This, of course, as just another way of saying that our story is true. The problem of evil, for example, is not a problem for our Story the way some people think it is. Rather it fits right in. Our whole Story from beginning to end is about the problem of evil and how that problem gets fixed. And there are many other things like this.

Third, our Story is verifiable. Since our Story is about reality, we can test reality to see if it’s true. We’re able to marshal persuasive evidence that God is real, that Jesus existed, was executed on a Roman Cross, and walked out of His grave three days later, that the world was designed for a purpose, that there is an afterlife—and a host of other important things pertaining to our Story. This is why Christianity is the only religion that has a apologetics as a subset of its theology.

What do you say to the many Christians who disagree with each other over theology and doctrine. How can they embrace a single Christian worldview?

Greg Koukl: The word “Christian” means something in particular. The basic outline and general truths and doctrines central to Christianity have been hammered out over 2000 years of reflection on the teachings of Jesus and his apostles. If you disagree with these foundational concerns—the kinds of things I focus on in The Story of Reality—then you’re simply not a Christian.

You may be a fantastic person, and you may have some wonderful religious views that might even turn out to be true, but the religion you’d be following would not be Christianity. If that sounds judgmental, it is a judgment. It’s a judgment about what words mean. It’s the same kind of judgment everyone makes whenever they have to distinguish between two different things. In one sense, then, Christians never disagree on the basics, because disagreeing on the basics means you’re not a Christian.

There are lots of other issues Christians quibble about, though, secondary matters that represent in-house disputes about things that are not central or foundational, but still could be important. That shouldn’t surprise us, though, because every worldview has its ambiguities—debatable elements that people simply will not see to eye on. There’s nothing wrong with that as long as the disagreement is principled and dignified. I actually think that arguments—as opposed to quarrels—are good things because they’re the best way to figure out what’s true. Share your reasons, listen carefully to each other, be nice, and may the best idea win.

How will your book change the way Christians live?

Greg Koukl: It’s hard to make a prediction here because different people respond in different ways to things they read. Peter says believers should “long for the pure milk of the word, so that by it [they] may grow in respect to salvation.” So, if people find in this book a manageable and orderly retelling of what the Word has to say about the unfolding Story of God working in the world, then they will grow spiritually as a result. They’ll have a renewed vision of God’s purposes for history and their place in it. Simply put, they will be more confident the Christian Story actually is true, and they will follow harder after God because of that confidence.

Is there anything else you’d like people to know about the book?

Greg Koukl: If some of your readers have seen Christian worldview books before and are thinking, “been there; done that,” I think they’re going to be surprised by what they find in The Story of Reality. I approach the topic in a very different way than most books on worldview. In tone, content, and style I like to think of the book as a Mere Christianity for a new generation, if the comparison doesn’t seem to bold. They won’t find a bunch of technical jargon or empty-sounding religious slogans. Instead, they will participate in a kind of relaxed conversation about a remarkable drama that we all participate in.

I also hope the reader will see that a chief reason for taking the Christian Story seriously is that it simply is—as I often say—“the best explanation for the way things are.”