Susan Hylen has written a new book entitled Finding Phoebe: What New Testament Women Were Really Like.

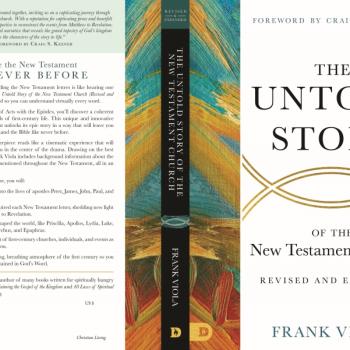

I’ll be using it as a source for my upcoming book The Untold Story of the New Testament Church (Revised and Expanded), due out in 2024 or 2025.

I caught up with Susan recently to discuss her book.

Enjoy!

When someone hears about a book and they ask, “What is your book about?” what they are really asking is, “What’s in it for me?” In other words, what will I get out of reading your book? What is the pay off for my time and energy and the cost of the book? What’s in it for me?

Please answer that for readers. What’s in it for them?

Many readers of the Bible have questions about the ways women are portrayed. On the one hand, we see women playing important roles in the communities around Jesus and Paul. On the other hand, we see New Testament authors saying women shouldn’t sepak, or that they should be subordinate to husbands.

This book provides a new way of understanding that conflicting evidence. Some social norms of the time encouraged women to defer to their male peers, but other norms encouraged women to take on leadership roles. Women played active roles in their families and communities.

Have you gotten any push book so far from critics? If so, what where their criticisms and what is your reply to them?

I haven’t had much pushback. In part, I think this may be because I’m not telling people how they should interpret Scripture—let alone whether their church should allow women to preach. The book provides historical resources to help people interpret Scripture better for their own context.

Give us two or three “aha!” moments that came to you when you were doing the research for the book, things that really impressed you that you didn’t know before.

Many readers assume, as I did, that women in the New Testament times couldn’t own property. I was surprised to learn that women’s property ownership was a regular part of everyday life—they owned about 1/3 of all property.

I was also under the impression that women were always under a man’s authority. So I was surprised to learn that it was rare for women to be under the legal authority of her husband. Although fathers did have authority over their children (both sons and daughters), when their father died they were legally independent.

Marriage didn’t change this independent status. If a woman’s father died and she later married, she remained legally independent. The wife was the one person in the household who wasn’t under her husband’s authority.

Regarding women in the first century, what was most striking about their ability to own property?

Most women owned some property. Some were incredibly wealthy—today we might call them the 1%! We see evidence of their wealth in inscriptions that praised their donation of temples, baths, and festivals to their cities.

But many women were middle class or poor. We see their ownership, too, in loan agreements for small sums or tax records showing modest amounts.

Perhaps most striking, we also see women using their property to improve their families’ lives. They make loans, collect rent, and ensure their crops are delivered to market. Activity like this suggests women had considerably more agency than we have imagined.

You devote two chapters in your book to marriage. What was most striking about marriage as it related to women in the first century?

In marriage, we again see both the restrictions of the culture and the agency of ancient women. Husbands were ideally thought to have higher status than their wives, and people thought it best for women to defer to their husbands.

However, women were also in charge of much of the household. And at the center of the household was the economic activity that kept it going. Women didn’t just keep house, they were central players in the economic life of their family.

Perhaps most interesting to me, though, was the realization that women gained social standing through marriage and childbirth. Because it gave them prestige, marriage wasn’t just restrictive for women, it also enabled them to engage their communities. Women who took on leadership roles brought honor to their families, and that benefited everyone.

What kind of education did women have in the first century?

Scholars disagree over educational levels in antiquity, but I think it’s fair to say that people got as much education as they needed and no more. If you were rich, you needed to understand literature and poetry so you could make polite conversation and display your status. If you were a shopkeeper, you didn’t need that, but you might still learn spelling and adding in order to keep records and tally someone’s bill.

Women participated in gaining honor for their families and in their business affairs, so it makes sense that women also got as much education as was deemed appropriate. Elite women were not as highly educated as men—in particular, they weren’t trained to give political speeches. Middle class women might have gained basic skills in order to better perform their duties and as a way of increasing their social standing.

Tell us about modesty among women in the first century.

The Greek word we often translate as “modesty” had a broader meaning, self-control. Self-control was one of the chief virtues of the period. It expressed a person’s ability not to be overly influenced by emotions like fear, grief, or anger, or by desires for food, sex, or luxury goods.

Self-control was a virtue for men and women, and it was also a qualification for leadership. Leaders who spent lavishly on dinner parties to increase their status had less money to spend on the public good. A ruler who got drunk at a party might make bad decisions (think of Herod killing John the Baptist).

There were some ways that self-control/modesty was gendered. For example, women exercised self-control by not displaying their wealth through gold, jewels, and elaborately braided hairstyles. By doing these things, women displayed qualities desired for leadership roles.

Were Jewish women different from Gentile women?

It’s important to remember that in the New Testament period, Jewish people have been subject to Greek (and then Roman) rule for four centuries! There was a lot of cultural sharing, and we should expect that social norms were affected by those interactions.

Although there’s not as much evidence to show what Jewish women were doing, in each of the chapters I point to what evidence we have of Jewish practices. Jewish women behaved similarly to Greek and Roman women. They owned property, ran businesses, were leaders in their communities, and valued norms of modesty.

Now we come to Phoebe.

I commend to you our sister Phoebe, a deacon of the church in Cenchreae. I ask you to receive her in the Lord in a way worthy of his people and to give her any help she may need from you, for she has been the benefactor of many people, including me. Romans 16:1-2

Phoebe is described as a “deacon” in Romans 16:1. In your view, what exactly was a deacon in the New Testament? While the word means servant, aren’t all believers servants? So what makes a deacon different from all the other believers who are serving in a local assembly? And can you give some examples of the difference?

We don’t have any sources that tell us what deacons did early on. But there are a number of New Testament verses that identify it as a leadership role.

Here, the way Paul identifies Phoebe as “a deacon of the church at Cenchreae,” it sounds like a title or role, something worth mentioning when you introduce someone. In Philippians 1:1, Paul greets the church at Philippi, “together with the overseers and deacons.” And 1 Timothy 3 lists qualifications for these two offices as well.

We don’t know what roles men or women deacons played in these communities. And there were certainly people who “served” others without a title. But in Phoebe’s case, it seems most likely that the word points to a designated role that was valued by her community.

This leads us to a related question, what was Phoebe’s role exactly in your view?

There isn’t really any historical evidence from the period when Paul wrote that can help us to answer this question. Later Christian sources give some more insight into what deacons did, but that only tells us how the role developed and not what was happening with Phoebe. Even in the later sources, there’s quite a bit of variety.

What we can see in these few verses in Romans is that Phoebe is Paul’s messenger to the church in Rome. She’s been a patron to him and others, and now Paul is using his reputation in the church to introduce her to those in Rome. She was the bearer of the letter and may have read it out loud to the congregation.

Do you believe that Phoebe was a businesswoman traveling to Rome from Cenchrea?

It seems likely Phoebe had some other reason to visit Rome. It would be expensive for someone to make the trip just to deliver a letter. Paul may have decided to write his letter at that moment because he knew he had a trusted delivery person.

The evidence that women were involved in business and that they traveled makes it seem at least possible this was the case for Phoebe. (For example, Lydia, mentioned in Acts 16, is a business woman from Thyatira, but she’s in Philippi when Paul meets her.) People also traveled to visit family members, so we can’t be too sure about Phoebe’s agenda in Rome.

How do you address what some call the “limiting passage” in 1 Timothy 2. Can you give us a quick summary of how you interpret that text, specifically the part where Paul allegedly says he doesn’t want women to teach men?

My intention in the book isn’t to give a single “answer” to a passage like this, but to provide resources for readers to better understand the context. So I point out that it was common wisdom for ancient people to say that women should defer to men, and that it was a virtue to remain silent among people of higher status.

Practicing these virtues, however, didn’t eliminate women from leadership roles. There were other social norms that supported women’s activity and even encouraged their speech. A woman might speak boldly on behalf of her community (or faith) and this could be acknowledged as virtuous.

Also, explain the bit (in that same passage) about childbearing. That she shall be “saved through childbearing?” What on earth does that mean?

That’s a question many readers have! It’s a strange verse because 1 Timothy uses the word “saved” that is elsewhere used to express religious salvation. The statement doesn’t fit our expectations that, whatever gender differences there may have been, the means of salvation through Christ are the same for all.

In the historical context, childbearing was a sign of civic responsibility, both for men and women. The behavior of one’s children was often said to reflect on the parents’ virtue. So it may be that, despite the way the author identifies Eve as a “transgressor” or “sinner,” he still may understand women as capable of virtue, which could be expressed in this traditional way.

What about the other limiting passage in 1 Corinthians 14? What’s your take on that passage?

Women should remain silent in the churches. They are not allowed to speak, but must be in submission, as the law says. If they want to inquire about something, they should ask their own husbands at home; for it is disgraceful for a woman to speak in the church. 1 Corinthians 14:34-35

Similar to the passage above, I take this as a statement of common cultural norms that saw wives as virtuous when they let their husbands speak on behalf of the family. Even so, the same ancient sources acknowledge women’s leadership and even their speech. They didn’t always see women’s speech as “breaking the rules” of silence.

What else would you like readers to know about your book?

In addition to helping individual readers with questions about women’s roles, I hope that my book will be a resource for groups who want to study these questions together. Each chapter closes with open-ended questions that prompt reflection on Scripture. When we join together to discern what God is saying to us in Scripture, I believe that the Holy Spirit is present with us and guides us toward a faithful interpretation.