The building looked like the love child of a logic problem and a crossword puzzle. Richard Powers, Orfeo

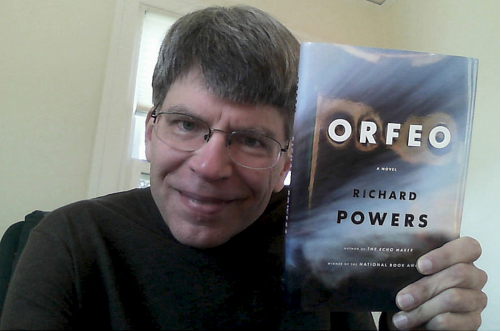

During the summer I tend to plow through a book per week, making up for all of the months during the academic year when I do not have the time to read anything other than what I have assigned the students or have been assigned by my colleagues and superiors.  Last week’s book was Richard Powers’ Orfeo. Powers is one of my favorite novelists, but I don’t recall ever having a conversation with anyone about his books. He’s the sort of author whose books win awards, whose novels reviewers rave about as “brilliant,” a “tour de force,” and “his generation’s Herman Melville,” but few people read. Orfeo is his eleventh novel—I’ve read them all, but could not tell you off the top of my head the plot of any one of them. Powers is incredibly smart, knows a ton about classical music, science, philosophy, politics and a bunch of other things—and he enjoys showing off his intelligence. His books often strike me as clumps of genius loosely connected by characters and a plot. What makes me keep track of when the next Richard Powers novel is coming out and purchasing it as soon as it is released is his mastery of the English language. I can think of no author—and I’ve read many—who astounds me more often, page after page, with a phrase or descriptive sentence that makes me put the book down and simply say “Wow. That’s beautiful” (or brilliant or a tour de force). Orfeo is no exception.

Last week’s book was Richard Powers’ Orfeo. Powers is one of my favorite novelists, but I don’t recall ever having a conversation with anyone about his books. He’s the sort of author whose books win awards, whose novels reviewers rave about as “brilliant,” a “tour de force,” and “his generation’s Herman Melville,” but few people read. Orfeo is his eleventh novel—I’ve read them all, but could not tell you off the top of my head the plot of any one of them. Powers is incredibly smart, knows a ton about classical music, science, philosophy, politics and a bunch of other things—and he enjoys showing off his intelligence. His books often strike me as clumps of genius loosely connected by characters and a plot. What makes me keep track of when the next Richard Powers novel is coming out and purchasing it as soon as it is released is his mastery of the English language. I can think of no author—and I’ve read many—who astounds me more often, page after page, with a phrase or descriptive sentence that makes me put the book down and simply say “Wow. That’s beautiful” (or brilliant or a tour de force). Orfeo is no exception.

And so she sat pushing her pen across the page like a pilgrim slogging to Compostela.

Replace “pushing her pen” with “clacking his laptop keys” and I know exactly what Powers is describing. I’ve never made the pilgrimage to Compostela, but have talked to a few persons who have. It takes daily preparation beforehand, but above all requires a daily commitment. Some days will be bright and beautiful, filled with great conversation and a general joie de vivre. Other days will be drizzly, cold, gloomy, and invite one to stay in bed. But getting to Compostela requires putting in the miles every day, regardless of weather and/or emotional contingencies. Writing is like that. Waiting until the stars are aligned and you have something important to say means that you will wait forever. It’s like police work—days on end of boredom punctuated by unpredictable moments of sheer terror (or inspiration or insight if one is writing—hopefully writing doesn’t always inspire terror). The immediacy of regular blog writing is helpful—committing myself to two new posts every week guarantees that I won’t wait on elusive inspiration.

Replace “pushing her pen” with “clacking his laptop keys” and I know exactly what Powers is describing. I’ve never made the pilgrimage to Compostela, but have talked to a few persons who have. It takes daily preparation beforehand, but above all requires a daily commitment. Some days will be bright and beautiful, filled with great conversation and a general joie de vivre. Other days will be drizzly, cold, gloomy, and invite one to stay in bed. But getting to Compostela requires putting in the miles every day, regardless of weather and/or emotional contingencies. Writing is like that. Waiting until the stars are aligned and you have something important to say means that you will wait forever. It’s like police work—days on end of boredom punctuated by unpredictable moments of sheer terror (or inspiration or insight if one is writing—hopefully writing doesn’t always inspire terror). The immediacy of regular blog writing is helpful—committing myself to two new posts every week guarantees that I won’t wait on elusive inspiration.

Dissonance is a beauty that familiarity hasn’t yet destroyed.

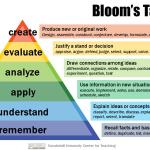

I try to introduce my students to the important concept of cognitive dissonance all the time, usually starting with a reminder of the Sesame Street game: “One of these things is not like the other, one of these things doesn’t belong.” Our natural tendency is to resolve dissonance into similarity, even if it requires forcing the issue. But part of a liberal education is a growing awareness that sometimes contradictions not only cannot be but should not be resolved. Familiarity breeds contempt, but dissonance keep us on our toes—and that’s a beautiful thing.

I try to introduce my students to the important concept of cognitive dissonance all the time, usually starting with a reminder of the Sesame Street game: “One of these things is not like the other, one of these things doesn’t belong.” Our natural tendency is to resolve dissonance into similarity, even if it requires forcing the issue. But part of a liberal education is a growing awareness that sometimes contradictions not only cannot be but should not be resolved. Familiarity breeds contempt, but dissonance keep us on our toes—and that’s a beautiful thing.

“Isn’t the point of music to move listeners?”

“No. The point of music is to wake listeners up. To break all our ready-made habits.”

T he same is true of the learning process. Important thinkers from Aristotle to Simone Weil tell us that the struggle and process involved in grappling with unfamiliar ideas is often far more important than getting “the right answer.” In a recent article in the Huffington Post, Christopher Nelson (President of my alma mater St. John’s College) nails it: “A liberal education, especially, inspires students to value struggle. By grappling with authors and ideas that demand the greatest level of intellectual intensity—and this is especially true in subjects that are difficult and uncongenial—students learn that they stretch themselves more through struggle, whether or not they win the match.”

he same is true of the learning process. Important thinkers from Aristotle to Simone Weil tell us that the struggle and process involved in grappling with unfamiliar ideas is often far more important than getting “the right answer.” In a recent article in the Huffington Post, Christopher Nelson (President of my alma mater St. John’s College) nails it: “A liberal education, especially, inspires students to value struggle. By grappling with authors and ideas that demand the greatest level of intellectual intensity—and this is especially true in subjects that are difficult and uncongenial—students learn that they stretch themselves more through struggle, whether or not they win the match.”

We are brought back to ourselves by solitude, and from ourselves to God is only a step.

With this I return, as I frequently do, to a phrase from an obscure medieval nun that captures the essence of what I learned on sabbatical five years ago: My deepest me is God. Using the vocabulary of Christianity, Powers is identifying the truest meaning of incarnation, the divine embedded in human form. The point is just as powerful when taken outside of a religious context. Usually what I most need and desire cannot be found by turning outward to things, persons, jobs or events. The source of everything I need is internal.  I spent all of last semester with a bunch of sophomores studying how various people in the worst possible circumstances time and again came to this realization. Etty Hillesum was a case in point.

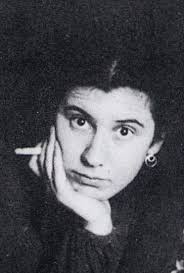

I spent all of last semester with a bunch of sophomores studying how various people in the worst possible circumstances time and again came to this realization. Etty Hillesum was a case in point.

Etty Hillesum has been described as “the adult counterpart to Anne Frank”; her diary and letters, published as An Interrupted Life, reveal a remarkable awareness and compassion in the midst of some of humanity’s darkest days. She died in Auschwitz in 1943 at the age of twenty-nine. Knowing that I taught a colloquium on various issues related to the Holocaust last semester, the President of my college recommended it to me at lunch the other day. I knew that the recommendation was a fortuitous one as soon as I read the introduction by Jan Gaarlandt. Gaarlandt writes of Hillesum’s “totally unconventional” spirituality and rejects the attempts by both Jews and Christians to claim her as typically Jewish or typically Christian as “unprofitable.” As I suspect is the case with most persons described as “religious,” Etty’s spirituality was uniquely her own; she regularly addresses God in her diary and letters as she would address herself.

I hold a silly, naïve, or deadly serious conversation with what is deepest inside me, which for the sake of convenience I call God . . . I repose in myself. And that part of myself, that deepest and richest part in which I repose, is what I call “God.”

This may not be “typical” in any sense, but it captures the incarnational heart of Christianity beautifully. As the medieval sister said, My deepest me is God.