A young former-buttoned-down conservative at CPAC (the Conservative Political Action Conference) said that he has moved to the alt.right because it feels like “the new punk rock.” Scott Galupo of The Week discussed this with Daniel Wattenberg, a former punk rocker, now a respectable editor.

A young former-buttoned-down conservative at CPAC (the Conservative Political Action Conference) said that he has moved to the alt.right because it feels like “the new punk rock.” Scott Galupo of The Week discussed this with Daniel Wattenberg, a former punk rocker, now a respectable editor.

Wattenberg disassociated punks with the alt.right, but he did see a connection to the Donald Trump phenomenon. He said, “I have to say, it does feel similar in a lot of ways, psychologically and emotionally,”

Wattenberg says that Trump and his supporters are to traditional conservatives as the punks were to the hippies. Trump and his supporters are to professional politicians as punk music was to progressive rock. Also, both Trumpism and punks are “transgressive” in defying political correctness.

Wattenberg and Galupo unpack those observations and more after the jump.

From Scott Galupo, Is Trumpism the new punk rock?, The Week:

The first thing one must understand about the right-wing character of punk, Wattenberg says, is not that its exponents were soi-disant Young Republicans, quoting Goldwater or God and Man at Yale. New York-centered punk began as “an intramural insurrection within the counterculture,” he says. It was the punks vs. their somnolent, sententious hippie older brothers and sisters, who had for years propounded what Wattenberg calls the “reverse pieties” of anti-Americanism and anti-commercialism and white guilt.

What does this have to do with the president and his core following?

Wattenberg says Trumpism was “an insurrection against Conservatism Inc.” — a political establishment that had become flabby, complacent, and self-indulgent in the same way that 1970s progressive rock music had grown bombastic, pretentious, and long-winded. Whereas Republicans before Trump had been terrified of deviating from orthodox positions on trade, the desirability of immigration, or the wisdom of the Iraq war, Trump thumbed his nose at this orthodoxy.

Then there’s Trump’s seeming amateurism — his “inexperience and rawness,” Wattenberg says. Just as punks weren’t trained musicians, Trump is frequently assailed for not playing politics the right way, that is, the professional way. When Wattenberg hears the media establishment pounce on Trump for falsehoods, misstatements, or exaggerations, he hears echoes of musical sophisticates belittling punk rock for its primitivism. Trump may get lost in the details, but he gets the big things attitudinally right. Put another way: He may know only three chords, but Wattenberg says his followers hear the “right three chords.”

He also sees in Trump a political manifestation of punk’s do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos. (By “do-it-yourself,” punks don’t mean changing the oil or remodeling your bathroom; it’s meant as a command: Write your own song. Paint your own painting.) Punk-rock bands created their own independent labels and staged gigs in small clubs or church basements. Trump lacked support from Republican Party elites in the same way that punks lacked support from major labels and promoters. So he ran a shoestring campaign and made himself recklessly accessible to the media in pursuit of free coverage.

Finally there is the transgressive appeal of Trump’s rejection of political correctness. Wattenberg says: “There’s power in that. Punks were also occasionally misrepresented as harboring fascist sympathies. Once they call you a fascist, there’s nothing more than they can say. That’s the source of excitement Milo [Yiannopoulos] generated on campus: ‘We’re free again.’ That’s the thrill and the power of busting taboos.”

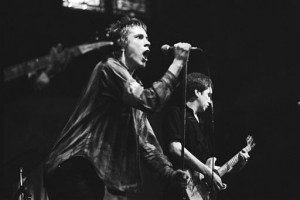

Photo: “Sex Pistols in Paradiso,” by Koen Suyk; Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Rijksfotoarchief: Fotocollectie Algemeen Nederlands Fotopersbureau (ANEFO), 1945-1989 – negatiefstroken zwart/wit, nummer toegang 2.24.01.05, bestanddeelnummer 928-9663 (Nationaal Archief) [CC BY-SA 3.0 nl (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/nl/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons