In our last post on Mark Mattes’s new book Martin Luther’s Theology of Beauty, we discussed how Luther moves from beauty as “perfection” to beauty as “gift.” Other facets of Luther’s view of beauty include his affirmation of matter, the senses, and emotions. (Yes, you read that last part right. Lutherans have the reputation of downplaying the emotions, but Mattes shows how important they are for Luther and the Christian life.)

St. Augustine’s Confessions is a wonderful book, but every time I read it (as when I was teaching it) I am struck by the way the great theologian struggles against ordinary pleasures. He feels guilty for enjoying food too much, even for taking too much pleasure in church music, thinking that he needs to take pleasure in God alone rather than all of these material things.

Such squeamishness derives, of course, from St. Augustine’s Platonism. The material world is only a shadow of the true reality in the realm of the ideals. While material objects are connected to those ideals–so that they partake of transcendental beauty–we should move from these earthly copies to the transcendental reality that they merely reflect. For Christian Platonists, the ultimate transcendental reality and the source of all that is true, good, and beautiful, is God.

Platonism thus downplays the significance of matter, the senses, and the emotions. And Plato famously banished artists from his republic. Similarly, many theologians have banished artists from their churches.

But while Luther is on record as preferring Plato to Aristotle (in the Heideberg Disputation Thesis #36), Mattes shows that he is opposed to Platonic theology.

For Luther, all of Creation is a “mask of God.” That is to say, God is “hidden” in everything that He has made. To be “hidden” means to be present, but unseen. God’s providential care for and intimate involvement in the universe that He has made are such that He is not far away, as many people imagine God, a being far beyond the physical realm. Rather, He is very near, being present and active even in the most mundane aspects of the physical world. In the theology of vocation, as we have often said, God gives us our daily bread by means of farmers, bakers, and other economic vocations. But it is God who gives us our daily bread, as the Lord’s Prayer makes clear, doing so by working through physical human beings and natural and economic processes. Similarly, Luther believes that God is hidden throughout His physical realm.

This is not pantheism–God is distinct from His creation and does indeed transcend it. This is not advocating “natural theology,” since God is hidden, not revealed. Nor is God’s hiddenness in created things “sacramental,” Mattes observes, since His presence is not saving. Those whose knowledge of God comes only from the creation may get a glimpse of His Law, His power, His wrath, His beauty–or, as we see so often today, they may gain the impression of His indifference.

To find the revealed God, we must have recourse to His Word. Only by His Word can we realize our lostness, learn of God’s incarnation, encounter Christ and His atoning death and resurrection, and through the Holy Spirit receive the gift of faith. Mattes gives a great quotation from Luther:

“Although [God] is present in all creatures and I might find him in stone, in fire, in water, or even in a rope, for he certainly is there, yet he does not wish that I seek him there apart from m the Word, and [thereby] cast myself into the fire or the water, or hang myself on the rope. He is present everywhere, but does not wish that you grope for him everywhere. Grope, rather, where the Word is, and there you will lay hold of him in the right way” (LW 36:342).

Two places “where the Word is” are Baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Because we are physical creatures, God reaches us by physical things–water, bread, wine–that are joined to the Word of the Gospel, turning them into means by which the Holy Spirit works and Christ is present, creating and increasing our faith.

On the other side of justification by faith, though, when a sinner becomes a new creation in Christ, the created world is perceived differently. Our “senses” are opened, says Luther, and we know that the Hidden God, through it all, is gracious. By faith we see His glory and His gifts everywhere. The birds in their singing, says Luther, seem to be preaching the Gospel.

Whereas Platonists stress the unreliability of the senses, Luther stresses that for us physical creatures, the senses are how we know reality and experience God’s gifts. Thus, again, God comes to us not simply through our intellect but through our senses–in receiving Christ’s body and blood when we eat the bread and drink the wine of Holy Communion, when “faith comes by hearing” the Word of God (Romans 10:17).

Another element of Platonism that Luther rejects is the exaltation of reason, as the highest human faculty, which must subordinate the “passions” and human emotions. Luther, says Mattes, balances reason and emotions. Neither are reliable when it comes to God. We must know Him by faith, not the intellect nor the feelings. For those who have been justified by faith in Christ, reason is useful again, but so are the emotions. Christianity is not stoicism, and the Christian life is full of joy, sorrow, and the whole gamut of emotions.

Luther’s affirmation of matter, the senses, and the emotions–to a larger degree than most theologians–is the basis for a far-reaching theology of beauty. So says Mattes in his remarkable, paradigm-shifting book.

In a later post, we’ll discuss how all of this applies to music and the other arts.

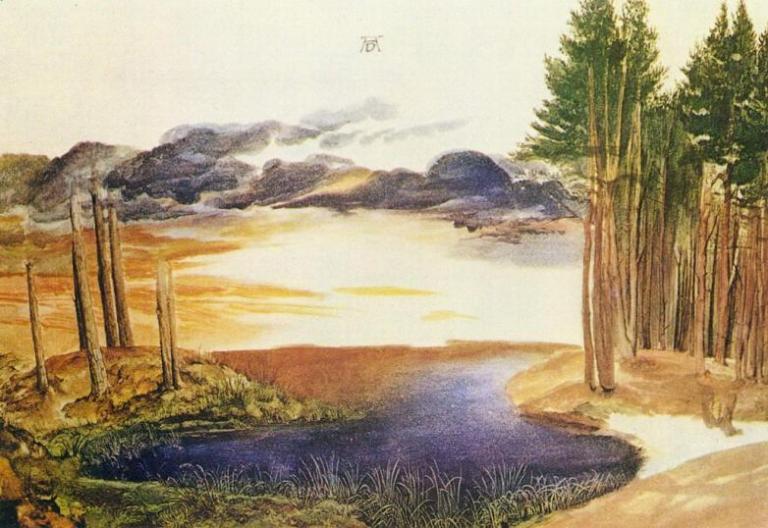

Illustration, “Pond in the Woods,” by Albrecht Dürer [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. [Notice the difference between this painting by a Luther-leaning artist, which draws on the sense-impressions of the physical world, and the more idealized paintings by the artists of the southern Renaissance, such as Leonardo da Vinci, who were influenced by the neo-Platonists.]