Just as some liberal Bible scholars have claimed that belief in Christ’s divinity “evolved” over some centuries of tradition, some have claimed that the emphasis on the Cross of Jesus Christ, along with the atonement and everything else it represents, only developed after the time of Constantine. They say that because Christian visual art did not depict Christ on the Cross until the 4th century. Actual evidence, however, shoots down both assertions from the “evolution of doctrine” school.

We have exploded that first claim, about Christ’s deity, in our post about the second-generation Christian testimonies to the deity of Christ. Paul McCain sent me some research from a few years ago about the centrality of the Cross among second-generation Christians–that is, Christians who were converted by the apostles or their contemporaries. It also addresses the issue of visual images of the Cross.

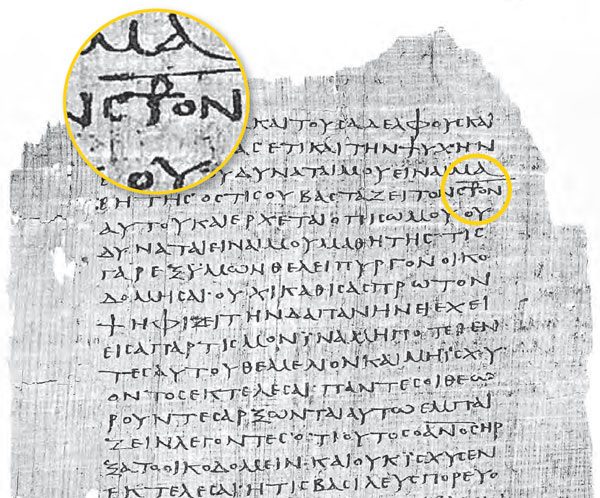

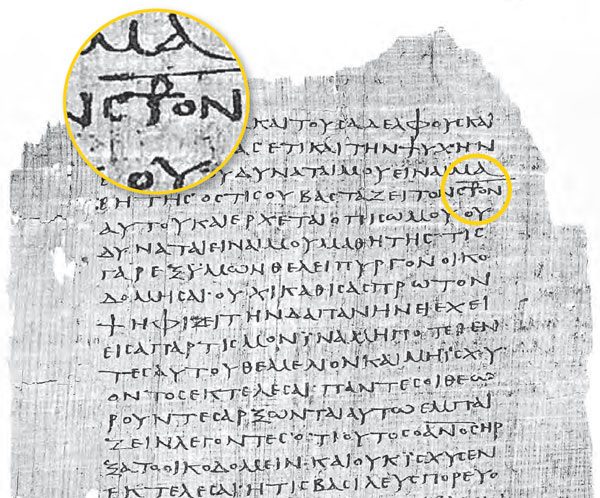

University of Edinburgh Bible scholar and church historian Larry Hurtado has studied the use of the “Staurogram,” which is prominent in Christian manuscripts and inscriptions beginning in the second century (that is, the 100’s A.D.–Jesus died probably in 35 A.D.). This is the superimposition of the Greek letter Tau (our “T”) and the Greek letter Rho (our “r” sound represented by what looks like our letter “P”). So a staurogram looks like this:  .

.

It derives from an abbreviation of stauros, which means “Cross,” and related words such as stauroō, meaning “crucify.” Early Christians began using this symbol when they were writing about Christ’s cross. Then the symbol began to be used for Christ Himself.

This pre-dated the more familiar Chi-Rho, the superimposition of X and P, standing for the first two letters in “Christ.”

Hurtado shows that the letter T had already been associated with the Cross. The added “P” not only includes a needed letter for the abbreviation of the word, Hurtado argues, it is also a visual suggestion of the head of someone on the cross.

The staurogram would thus be the earliest visual depiction of Christ on the Cross, a precursor to the crucifix, an important detail in the history of Christian iconography and the history of art.

Furthermore, it shows that, very early, Christ was thought of in terms of the Cross.

The above illustration shows a manuscript of the Gospel of Luke, zeroing in on the staurogram in Luke 14:27: “Whoever does not bear his own cross and come after me cannot be my disciple.” (ὅστις οὐ βαστάζει τὸν σταυρὸν ἑαυτοῦ καὶ ἔρχεται ὀπίσω μου, οὐ δύναται εἶναί μου μαθητής. Here the staurogram takes the place of the word “σταυρὸν.”) Interestingly, this would suggest that the cross the disciple must bear is connected to Christ’s cross.

For more details, go here. And here is Prof. Hurtado’s scholarly paper on the subject, which is full of other fascinating information about the early church.

Two more observations of my own:

(1) It is appropriate that the earliest Christians would focus on words and the Word, rather than visual images such as those employed by the pagans who were still in ascendancy.

(2) A written word is itself a visual image. It is an image of sounds, but it is no less visual.

Photo by Unknown – Papyrus Bodmer XIV-XV; Papyrus 75 (Gregory-Aland), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25964413