Is Bach Lutheran? The question is like, “Is the Pope Catholic?” OK, there may now be some question about that, but not about Bach among his fellow Lutherans, who know him as their greatest artist. And yet some critics have been saying that Bach “was a forward-looking, quasi-scientific thinker who had little or no genuine interest in traditional religion.”

Setting aside the counter-historical assumption that a person can’t be forward looking and scientific while holding to traditional religion, the critics who say that are just demonstrably wrong when it comes to Bach’s faith.

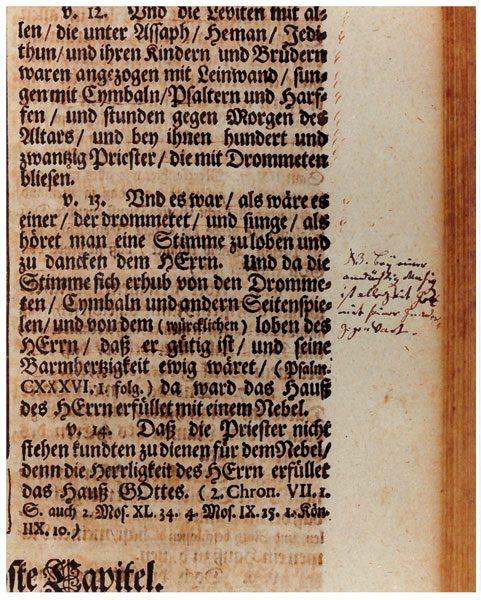

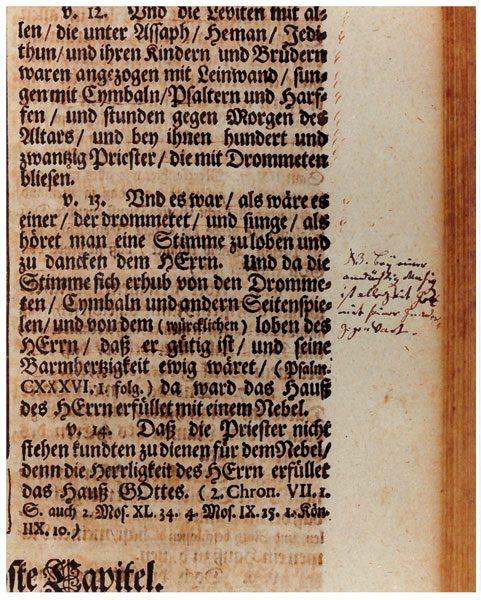

And major evidence for what that faith consists of can be found in Bach’s Bible with its extensive underlining, notes, and marginalia. That text, a study Bible with commentary by Abraham Calov mostly drawn from Luther’s writings, happens to be in the library of Concordia Seminary in St. Louis. (I have held it in my hands and leafed through it!)

Now a facsimile edition has been prepared for the low, low price of $5,000. (It isn’t on Amazon. You can get it here.)

This enables scholars to see for themselves that Bach was a Bible-believing, evangelical, Lutheran Christian.

An article in the New York Times, no less, underscores that fact. Written by Michael Marissen, the author of the excellent Bach & God, the article has the unpromising title Bach Was Far More Religious Than You Might Think (at least, presumably, more religious than most readers of the New York Times think).

But Marissen’s article makes brilliant use of Bach’s Bible. For example, the Calov Study Bible was a great resource, but it was filled with typographical errors. Bach’s copy contains many corrections that the composer inserted into the text, based on a better edition of Luther’s translation. Several times, Bach’s emendation is itself incorrect, substituting a similar-sounding word for the correct rendition. Which suggests that Bach was listening to the Bible being read.

Marissen concludes that Bach was following along with his Bible, pen in hand and noting corrections, as someone else was reading the Scriptures out loud. Marissen says this would probably have been in connection with family devotions, with some of Bach’s 20 children taking turns reading the Bible.

Note too Bach’s reflections on vocation, as Marissen unpacks them.

From Michael Marissen, Bach Was Far More Religious Than You Might Think, New York Times, March 30, 2018:

Bach biographers don’t have it easy. Has there ever been a composer who wrote so much extraordinary music and left so little documentation of his personal life?

Life-writing abhors a vacuum, and experts have indulged in all manner of speculation, generally mirroring their own approaches to the world, about how Bach must have understood himself and his works.

The current fancy is that Bach was a forward-looking, quasi-scientific thinker who had little or no genuine interest in traditional religion. “Bach’s Dialogue With Modernity,” one recent, indicative book is called. In arriving at this view, scholars have ignored, underestimated or misinterpreted a rich source of evidence: Bach’s personal three-volume Study Bible, extensively marked with his own notations. A proper assessment of this document renders absurd any notion that Bach was a progressivist or a secularist.

Bach’s copy of these tomes — which were published in 1681-82 with commentary culled by Abraham Calov from Martin Luther’s sermons and other writings — was unexpectedly discovered in the 1930s among the belongings of a German immigrant family in Frankenmuth, Mich., and is housed today at Concordia Seminary Library in St. Louis. An enterprising publisher in the Netherlands, the Uitgeverij Van Wijnen, has now issued a spectacular facsimile.

All three volumes are inscribed “JSBach.1733” and contain a host of handwritten corrections and comments. Bach handwriting experts have identified the vast majority of these verbal entries as “definitely Bach” or “probably Bach.” Hundreds of passages are further scrawled with marginal dashes and other nonverbal markings. Although these are harder to evaluate, physicists at the Crocker Nuclear Laboratory have concluded through ink analysis that “with high probability, Bach was also responsible for the underlinings and marginal marks.”

Where does all this science get us? Bach’s notations bear witness to a life of conservative Lutheran observance.

[Keep reading. . .]

Illustration: Bach’s annotation on 2 Chronicles 5: 13, translation by Martin Luther (1483-1546), Abraham Calov (1612-1686), Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) (http://bach.csl.edu/media/calov) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

HT: Paul McCain