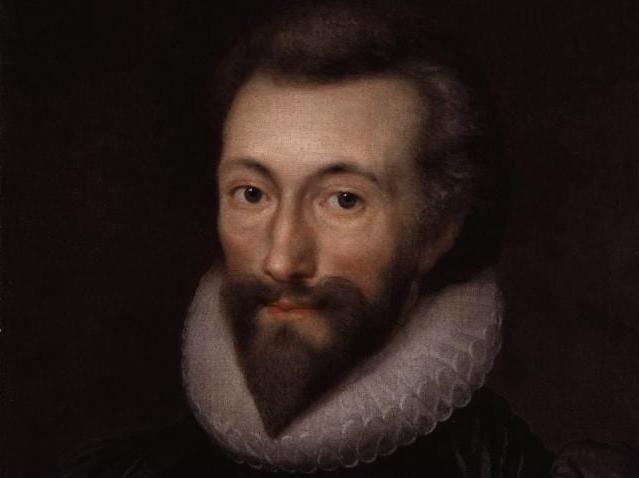

John Donne, one of the greatest lyric poets in the English language, fell sick, possibly from a typhus epidemic. In the course of his illness, which could have been fatal, and after his recovery, Donne wrote a series of meditations on the experience entitled Devotions upon Emergent Occasions.

Besides being a dazzling masterpiece of English prose, the Devotions are a classic example of Christian meditation. Their reflections on sickness, facing death, and trusting in God through afflictions are startlingly relevant for today’s coronavirus epidemic.

The devotions follow the entire course of the illness, with a meditation on every stage: the first faint symptoms; starting to feel really bad; going to bed; calling the physician; the physician is worried; they try various medicines; the patient keeps getting worse; the patient (Donne) realizes that he is probably going to die; he starts feeling better; he can get out of bed; he worries about a relapse, etc.

In all, there are 23 stages of the illness and 23 meditations, following the traditional meditative structure designed to engage all of the faculties of the mind. Each one is structured like this (1) The “Meditation” based on a vivid description (the “composition of place,” an exercise of the memory and the imagination); (2) The “Expostulation,” an intense argument with himself designed to correct his shortcomings (the “analysis,” engaging the intellect); and (3) A “Prayer” addressed to God (the “colloquy,” an address to God engaging the will).

The devotions are all worth reading in their entirety–they would make a good Lenten reading project. (The timing is perfect! Start today. If you read one of the Devotions per day, you will finish all 23 on the day before Easter! You can read them online here. You can download a Kindle edition for free. You get a hard copy here. )

I will give you the most famous, Meditation XVII, in its entirety (my bolds). The bed-ridden patient hears a nearby church tolling a bell, which is the custom when a member of the parish dies:

Nunc Lento Sonitu Dicunt, Morieris (Now this bell, tolling softly for another, says to me, Thou must die.)

Perchance, he for whom this bell tolls may be so ill, as that he knows not it tolls for him; and perchance I may think myself so much better than I am, as that they who are about me, and see my state, may have caused it to toll for me, and I know not that. The church is catholic, universal, so are all her actions; all that she does belongs to all. When she baptizes a child, that action concerns me; for that child is thereby connected to that body which is my head too, and ingrafted into that body whereof I am a member. And when she buries a man, that action concerns me: all mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; and every chapter must be so translated; God employs several translators; some pieces are translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some by justice; but God’s hand is in every translation, and his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again for that library where every book shall lie open to one another. As therefore the bell that rings to a sermon calls not upon the preacher only, but upon the congregation to come, so this bell calls us all; but how much more me, who am brought so near the door by this sickness.

There was a contention as far as a suit (in which both piety and dignity, religion and estimation, were mingled), which of the religious orders should ring to prayers first in the morning; and it was determined, that they should ring first that rose earliest. If we understand aright the dignity of this bell that tolls for our evening prayer, we would be glad to make it ours by rising early, in that application, that it might be ours as well as his, whose indeed it is.

The bell doth toll for him that thinks it doth; and though it intermit again, yet from that minute that this occasion wrought upon him, he is united to God. Who casts not up his eye to the sun when it rises? but who takes off his eye from a comet when that breaks out? Who bends not his ear to any bell which upon any occasion rings? but who can remove it from that bell which is passing a piece of himself out of this world?

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

Neither can we call this a begging of misery, or a borrowing of misery, as though we were not miserable enough of ourselves, but must fetch in more from the next house, in taking upon us the misery of our neighbours. Truly it were an excusable covetousness if we did, for affliction is a treasure, and scarce any man hath enough of it. No man hath affliction enough that is not matured and ripened by it, and made fit for God by that affliction. If a man carry treasure in bullion, or in a wedge of gold, and have none coined into current money, his treasure will not defray him as he travels. Tribulation is treasure in the nature of it, but it is not current money in the use of it, except we get nearer and nearer our home, heaven, by it. Another man may be sick too, and sick to death, and this affliction may lie in his bowels, as gold in a mine, and be of no use to him; but this bell, that tells me of his affliction, digs out and applies that gold to me: if by this consideration of another’s danger I take mine own into contemplation, and so secure myself, by making my recourse to my God, who is our only security.

Donne’s point is that human beings are connected with each other, which is particularly true of Christians, who by baptism are all engrafted into the same body, that of Jesus Christ. Thus, we can grow not only from our own afflictions but from the afflictions of others, as our empathy for them makes us realize our own mortality.

Image: John Donne by Isaac Oliver (ca. 1622), National Portrait Gallery / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons