In my new book Post-Christian: A Guide to Contemporary Thought and Culture, I explore the phenomenon of “secularism,” the attempt to do without religion and the prospects of bringing it back. Among many other things, I look at what has been happening in Europe, for most of its history the heart of Christendom, but not any longer.

The French political scientist Olivier Roy has written a book on the subject entitled Is Europe Christian? It’s a more complicated question than it sounds. Judging from a review in the Wall Street Journal and reading the “Look Inside” feature on Amazon, his findings seem to support my own, though I am more optimistic than he is about the possibility of Christianity–if not political “Christendom”–making a comeback.

Prof. Roy makes the point that “secularization. . .does not necessarily mean dechristianization.” And, unlike so many other scholars, he emphasizes the difference between Lutheranism (which, with its doctrine of the Two Kingdoms and vocation is “self-secularizing,” giving religious significance to the secular realm) and Calvinism (which tends to seek Christian rule of the secular order). He also notes the difference between both of these traditions and American Protestantism.

The reviewer, Walter Russell Mead, notes that American Christians, being individualists, approach such questions as the title of this book in terms of the number of Europeans who believe the Christian message. Europeans, though, approach religion more collectively, “as a public, political, and legal force.”

Indeed, many religions–Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Shintoism, etc.–are matters of cultural identity, rather than, or at least in addition to, an adherent’s personal beliefs. Christianity, in contrast, is for people “from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages” (Revelation 7:9) and has to do with a person’s faith in Christ. And yet, sometimes Christianity too is reduced to a matter of what group you belong to rather than what you believe. Thus, Catholic politicians can support abortion, though it violates essential teachings of their church, and still insist they are “good Catholics” because their church membership goes back in their family for generations. Often this belonging rather than believing mentality is connected to ethnicity–with Irish, Italian, and Hispanic Catholics; Russian, Serbian, or Middle Eastern Orthodox; and, yes, German or Scandinavian Lutherans.

So Prof. Roy focuses not upon beliefs or church attendance (a measure favored by social scientists since it is so quantifiable), but on Christian identity and Christian culture. These are still very much evident in Europe. I make the point that although they are not saving faith, but they are not nothing, and they constitute an infrastructure that could bring true Christianity back, especially with the influence of immigration from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East–the rest of the world that is emphatically not secularized and where Christianity is booming–and the extraordinary phenomenon of Muslims in Europe converting to Christianity.

Prof. Roy, though, thinks even Christian culture, while significant, is fading away now. In a compelling and widely applicable analysis, he says that Christianity is being replaced by “the religion of desire.”

From Walter Russell Mead, ‘Is Europe Christian?’ Review: Good Faith Estimate: As European churches vanish, the struggle continues between Christian republican virtue and the new religion of desire, in The Wall Street Journal [subscription required]:

In Mr. Roy’s account, the real break came in the 1960s and ’70s. Up until that time, Christians and non-Christians in Europe largely shared a moral code. On issues such as homosexuality, abortion and the place of women in society, Europe’s communists and socialists found themselves in broad agreement with traditional Christian ideas. In most European countries, secular law tracked classical Christian moral codes pretty closely. The number of Christian believers was gradually and even inexorably declining, but the Christian foundations of public morality and public law remained strong.

Then, in the 1960s, Europeans (and Americans) began to leave traditional morals behind. Mr. Roy understands the shift as the emergence of an ethic based on the “desiring subject” as the source of all value in morals and of all legitimacy in politics. What humans desire to do, they have an inalienable right and even a duty to do—on the condition that they refrain from injuring others. This was a genuine revolution in civilization, one whose profound effects, Mr. Roy argues, we have yet to fully understand.

This was more than a change in sentiment, Mr. Roy says. Slowly at first and then with increasing force, laws and institutions were transformed by the religion of desire. The legal and cultural revolution continues today; ideas like gender fluidity represent the progress of a new understanding of humanity’s place in the world.

Nothing could be further from both traditional Christian ideas and the rival European tradition of civic republican virtue than the cult of the desiring subject, but so strong was the appeal of the idea that neither religious nor secular practices could stand long against it. Under the force of the transformative youth revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, old taboos against cohabitation before marriage, homosexuality, abortion and much else lost their hold on the public mind. . . .

In a somber conclusion, Mr. Roy speaks of a global cultural crisis. It is not possible, he believes, to build a sustainable social order around a collection of desiring subjects—yet the strength of the ideologies of the 1960s is too great to permit an alternative to emerge. For Europe, beset by a globalization that threatens its coherence and independence from the world’s superpowers, the only answer is to return to its roots. For Mr. Roy, those roots are Europe’s Christian heritage and the tradition of pre-1960s liberalism grounded in the enlightenment and classical ideas of civic and republican virtue. Europe is not, he concludes, very Christian today, and that bodes ill for Europe’s future.

This accords with my book’s contention that objective thinking has been replaced by the exaltation of the will, which, in turn, has meant the unbounded release of the appetite. What Shakespeare calls the “universal wolf” that devours everything, until it devours itself.

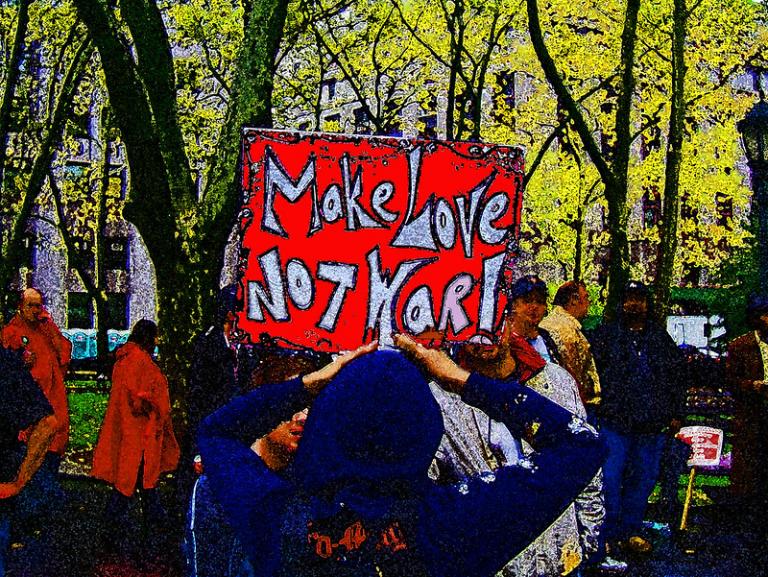

Illustration by Tony Fischer via Flickr, Creative Commons 2.0, no alterations.