I commend to you two posts from my fellow Patheos bloggers.

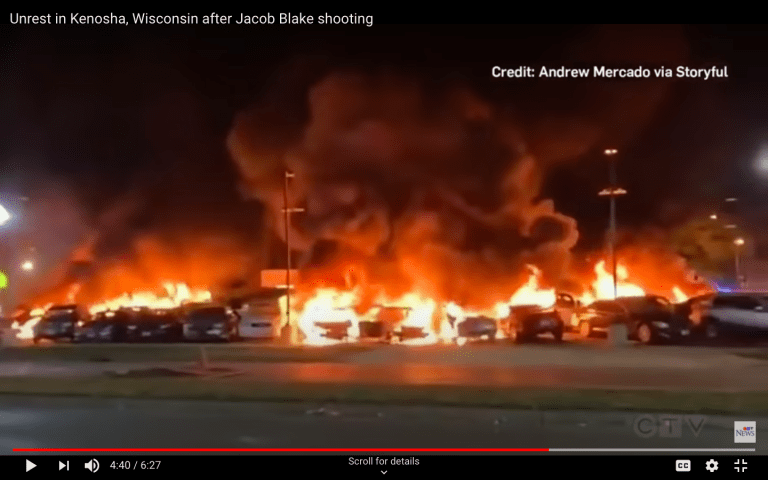

To learn what it feels like when law and order completely breaks down around you, read this post by Grayson Gilbert, who lives in Kenosha, Wisconsin, writing as his neighborhood is being looted and his community is going up in flames. In Kenosha, population 100,000, a police officer shot a black man, Jacob Blake, in the back–in front of his children, no less–paralyzing him. Of course this has sparked protests, and rightly so. But it has also become a pretext for visitors from Chicago and Milwaukee to pour into Kenosha, forming mobs that roam the streets, smashing windows, looting businesses, setting buildings on fire (including a church), and assaulting people on the streets. A white 17-year-old killed two protesters. In this climate of anarchy and social breakdown, Grayson recounts what it’s like to live in a community where all of this happening. He describes the smell of the burning city, evoking the fear of the citizens who live there, including his black neighbors, whose homes and livelihoods are being destroyed. His post defies summary and excerpting, so read it yourself.

Unjust police violence and racism are terrible and must be addressed. My question, though, is how does it advance the cause of Jacob Blake to commit violence against people who had nothing to do with his mistreatment? Black Lives Matter. So why should people supposedly committed to that cause–many of them white–loot black-owned businesses and set fire to black people’s neighborhoods?

For an answer to that question, read Timon Cline’s post, Chaos Creates Conservatives. It is mainly a tribute to the British conservative thinker Roger Scruton, who died this year. The essay is worth reading in its entirety, but let me just quote a few of its passages from Scruton.

As a young intellectual, Scruton was in Paris during the student riots of 1968. The violence and destruction he witnessed–similar to that in Kenosha, Portland, and other cities today–turned him into a conservative. He recounted his experience in an article published in 2003 in the New Criterion entitled Why I Became a Conservative.

He tells about a friend of his who was exhilarated by participating in the rioting.“She was very excited by the events… Great victories had been scored: policemen injured, cars set alight, slogans chanted, graffiti daubed. The bourgeoisie were on the run and soon the Old Fascist [de Gaulle] and his régime would be begging for mercy.”

So he asked her a question. “What, I asked, do you propose to put in the place of this “bourgeoisie” whom you so despise, and to whom you owe the freedom and prosperity that enable you to play on your toy barricades?”

She replied with a book: Foucault’s [The Order of Things], the bible of the soixante-huitards [the student protestors], the text which seemed to justify every form of transgression, by showing that obedience is merely defeat. It is an artful book, composed with a satanic mendacity, selectively appropriating facts in order to show that culture and knowledge are nothing but the “discourses” of power. The book is not a work of philosophy but an exercise in rhetoric. Its goal is subversion, not truth, and it is careful to argue—by the old nominalist sleight of hand that was surely invented by the Father of Lies—that “truth” requires inverted commas, that it changes from epoch to epoch, and is tied to the form of consciousness, the “episteme,” imposed by the class which profits from its propagation. The revolutionary spirit, which searches the world for things to hate, has found in Foucault a new literary formula. Look everywhere for power, he tells his readers, and you will find it. Where there is power there is oppression. And where there is oppression there is the right to destroy. In the street below my window was the translation of that message into deeds.

Cline comments, while quoting Scruton again: “Though Foucault is long dead, Scruton notes well his outsized, enduring legacy, solidified in seemingly every university reading list in Europe and America. ‘His vision of European culture as the institutionalized form of oppressive power is taught everywhere as gospel, to students who have neither the culture nor the religion to resist it.’”

I can also attest that the French post-modernist Michel Foucault is venerated on university campuses, and his reduction of all truth-claims, moral values, and cultural institutions to power and his insistence that all power is oppressive are foundational to today’s critical theory.

Cline says that Scruton found two answers to Foucault:

For the young Scruton, the antidote to Foucault was the Anglo-American common law tradition, a love for which he cultivated whilst studying for the bar. “Law,” he said, “is constrained at every point by reality, and utopian visions have no place in it.”

Moreover, the common law of England is proof that there is a real distinction between legitimate and illegitimate power, that power can exist without oppression, and that authority is a living force in human conduct. English law, I discovered, is the answer to Foucault.

The second answer Scruton found in the 18th-century Edmund Burke, the seminal conservative thinker who critiqued the lawlessness of the French Revolution. From Scruton’s essay, as quoted by Timon Cline:

Far from being the evil and obnoxious thing that my contemporaries held it to be, authority was, for Burke, the root of political order. Society, he argued, is not held together by the abstract rights of the citizen, as the French Revolutionaries supposed. It is held together by authority—by which is meant the right to obedience, rather than the mere power to compel it. And obedience, in its turn, is the prime virtue of political beings, the disposition which makes it possible to govern them, and without which societies crumble into ‘the dust and powder of individuality’… In effect Burke was upholding the old view of man in society, as subject of a sovereign, against the new view of him, as citizen of a state… Real freedom, concrete freedom, the freedom that can actually be defined, claimed, and granted, was not the opposite of obedience but its other side. The abstract, unreal freedom of the liberal intellect was really nothing more than childish disobedience, amplified into anarchy.

Here I think we can see where Christianity comes in: There is legitimate authority. Strictly speaking, God holds all authority, but His authority is masked in human vocations (such as that of parents, lawful rulers, etc.). Thus, as St. Paul says, “There is no authority except from God, and those that exist have been instituted by God” (Romans 13:1). And, yes, obedience–to God, to parents, to lawful rulers, etc.–is a virtue. Furthermore, power is not innately oppressive. God’s power is righteous, as is His power exercised through human vocations.

To be sure, human sin distorts both authority and power. But that authority and power can be exercised in a morally good way frees people from Foucault’s vicious circle: If power is always oppressive, overthrowing the oppressor by seizing power means becoming an oppressor oneself.

Whereas if authority and power can be exercised in a good way, there is a political way forward and justice–including for black people–becomes possible.