Not only do theologians have doctrinal differences. They also have differences about what doctrine even is. This is why liberal theologians can sound orthodox without being so and why ecumenical dialogues can find agreement where none exists.

Later came the notion that doctrine is experiential-expressive. That is, a description or an expression of people’s religious experience. According to this view, the Doctrine of the Trinity means that people have experienced God as Father, they have experienced Jesus as God, and they have experienced the Holy Spirit as God.

This view, which derives from 19th century theologians such as Schleiermacher and is held by modern Catholic theologians such as Karl Rahner, usually affirms a universal religious experience–so that Buddhists and Christians might have the same faith, though expressed differently–though I would say it accords more readily with relativism, since different people have different religious experiences, all of which can claim validity.

More recently is the notion that Lindbeck himself develops and holds to, that doctrine is cultural-linguistic. That is, an agreed-upon language that is adopted by a particular interpretive community, such as a church. The Doctrine of the Trinity, in this view, is the language that Christians have agreed to use–as worked out in the early church at the council of Nicaea and other discussions–when they talk about God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit.

This understanding of doctrine as language affirms the role of churches and their right to hold distinctive doctrines. Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists, Arminians, Baptists, Pentecostals, etc., each have their own language, though they can also share a language that is common to all Christians.

But Lindbeck also recommends this view for its ecumenical possibilities. Just as we can accept other cultures, we can accept other churches or even other religions as, in effect, cultures with different languages. This eliminates any question of conflicting truth claims. We just need to learn the other religion’s language, while still retaining our own.

Furthermore, if two different interpretive communities–say, Lutherans and Catholics–can agree to use the same language, even though they have historically meant different things by it–say, on justification–they can claim to be in doctrinal agreement with each other (as in the Joint Declaration on Justification).

This also, to me, explains how liberal–or Lindbeck’s “postliberal”–theologians can often sound orthodox, while not believing a word of it. They are using the orthodox language of their tradition.

This emphasis on language is not to be confused with a high view of God’s Word. Of course language is essential to human life and thought. But a dependence for doctrine on God’s Word sees this particular language as revelatory, as truths communicated by God Himself through human language, and not simply as the language of a human cultural community.

Kilcrease, in contrast, defends the propositional understanding of doctrine, a position held by the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod and other orthodox church bodies, as well as the more conservative theologians in their respective traditions.

When it comes to Kilcrease’s topic of the Atonement, the issue is not just how we experience it or how we should speak of it, but what happened on the Cross.

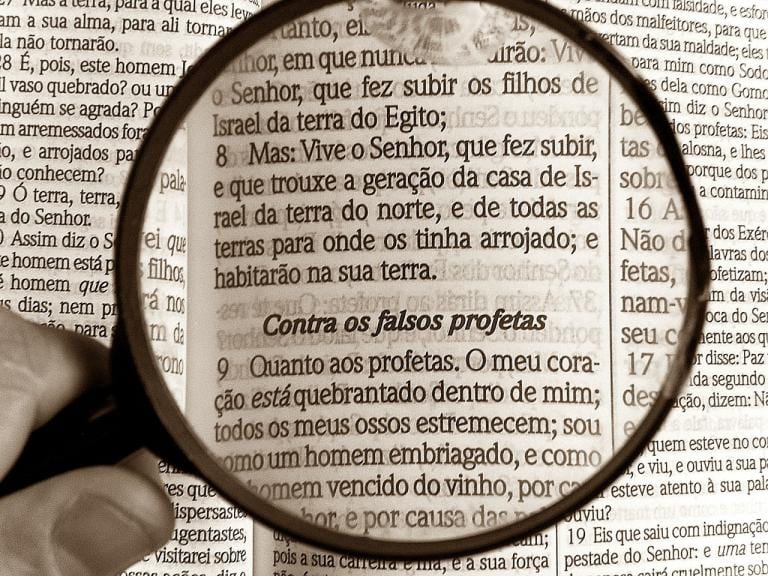

Image by sammisreachers from Pixabay