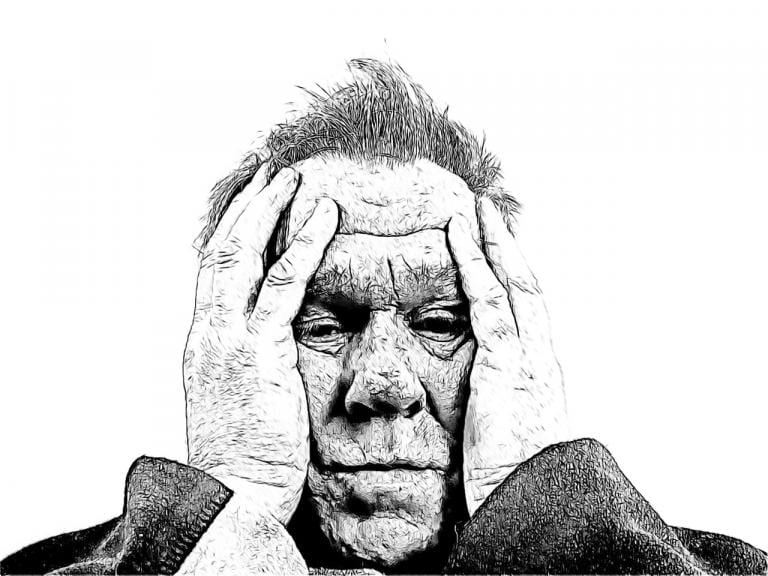

Nearly eight out of 10 Americans (77%) believe that 2020 has put the country into an “existential crisis.” And nearly two out of three (65%) say that they themselves have experienced such a crisis.

What do they mean by that? “Existential” in this context can be taken in two ways.

It can refer to questions of whether or not something or someone can continue to “exist.” COVID-19 is an “existential threat” because it can cause death. (Yes, Christians know that we continue to exist after death, but not everyone has that hope.) Also, the response to the virus has meant that many businesses–from providers of livelihoods to favorite shops and restaurants–have ceased to exist. Our political turmoil evidenced in the recent election has caused many Americans to worry about whether our democratic republic will continue to exist.

“Existential” can also refer to questions of meaning. In that sense, an “existential crisis” is an experience that makes people feel that their lives are meaningless. The study goes on to say that the respondents reported “feeling defeated,” feeling “overwhelmed,” lacking motivation, and questioning their identity. All of which would point to a crisis of meaning.

People find meaning in their work. The coronavirus lockdown prevented people from going to their workplace-either because they had to work from home or lost their jobs altogether–where they had colleagues, customers, and an outlet for their talents. The feeling of not contributing or not being worth anything makes a person doubt the meaning of their lives.

People find meaning in their relationships. The lockdowns did allow people to spend more time with their immediate families, which was often a good thing but sometimes led to conflicts. But they couldn’t go out with friends or visit loved ones who lived farther away. Isolation and loneliness can contribute to a sense of meaninglessness.

People find meaning in belonging to a nation. The racial protests occasioned by the police shootings have led to large-scale repudiations of American history and questioning of America’s worth. The presidential campaign set Americans against each other. The meaning of America seemed to slip away.

People find meaning in civic engagement. Both sides were frustrated in the outcome of the election, with progressives disappointed that the “blue wave” they counted on to sweep them into power never materialized, with many conservatives feeling that the election was rigged against them. Neither side considers the other side’s victories legitimate. Trust in first responders collapsed with the movement to “defund the police.” Protesters burned down communities, many of whose leaders lacked the resolve to defend them. Meanwhile, citizens grew disillusioned with their local, state, and national governments, which often seemed both overly harsh and ineffective. Our political and civic institutions lost their meaning.

People find meaning above all in their religion. The COVID-19 lockdown shut the doors of churches, and the state forbade congregations from meeting together for worship. Churches met virtually, but this was not the same as embodied, sacramental fellowship. Some Christians accepted the reasons for the emergency, while others resisted, but religious liberty was shaken. As other challenges to religious liberty continued to build–such as accusations that moral teachings constitute “discrimination”–the meaning of our meaning-bestowing institutions was weakened.

According to the “existentialist” philosophers, when you go through an “existential crisis” and confront the meaninglessness of your life, what you need to do is create your own meanings. This is the origin of our postmodern relativism, the notion that truth is not an objective discovery but a subjective “construction.”

We have certainly seen that response to the “existential crisis” of 2020, a year of fake news, conspiracy theories, untruths, impositions of power, and newly constructed explanatory paradigms. These have been spread by social media, Zoom, and other virtual technologies to which we have been confined.

Existential crises can lead to mental and social breakdown. Or they can function as a casting down of our idols, a destruction of complacency that can lead to conversion, to a life-changing confrontation with the only true source of meaning, not an institution, but God Himself.

Insofar as that happens, 2020 will have meaning after all.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay