One of my academic specialties has been Christian literature, and yet I had never heard of someone who may have been the first great Christian poet until we read one of the few English translations of his works in a church workers’ reading group that I go to. And reading his Lenten poetry has been a literary and spiritual revelation.

He is St. Romanos the Melodist, a Jewish convert who lived in the Byzantine empire from 490-556 A.D. He was a deacon, not a priest but someone who assisted in the services, and lived in Constantinople, serving as sacristan–an officer who took care of the physical building–in the magnificent cathedral known as the Hagia Sophia, which is still standing, though it has been turned into a mosque in present-day Turkey.

Romanos is said to have written some 1000 hymns, of which only 60 have survived, with 29 others attributed to him but of doubtful authorship. He specialized in the type of hymn known as a kontakion. Our hymns are mostly based on lyric poems, expressions of a single theme or emotion. Kontakia, on the other hand, are dramatic and narrative poems. That is, they are longer works that tell a story, usually from the Bible, and depict dialogues between the characters. In effect, they are sermons in verse, consisting of an exposition of Scripture by means of poetic devices.

Kontakia–the term deriving from the Greek word for the rod of the scroll, from which a cantor and lay singers would read–were sung in the liturgy, specifically during the evening Night Vigils, but they would also be featured in the regular divine service until the sack of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. A kontakion to the Virgin Mary, possibly by Romanos, is still a part of the Eastern Orthodox liturgy for Annunciation Day, and his hymn “My soul, my soul, why sleepest thou?” is sung during Lent, on the Thursday before Maundy Thursday.

Romanos wrote in Greek, but instead of the “qualitative” meter of classical Greek and Latin poetry, based on alternating long and short syllables, his verse is rhythmic. It also is full of penetrating, thought-provoking imagery, and is charged with passionately devout emotion. His Wikipedia article quotes the 19th century scholar Karl Krumbacher, who said,

In poetic talent, fire of inspiration, depth of feeling, and elevation of language, he far surpasses all the other melodes. The literary history of the future will perhaps acclaim Romanos for the greatest ecclesiastical poet of all ages.

And yet, hardly any of his poetry has been translated into English, until just this last year, when Andrew Mellas published his Hymns of Repentance. Part of the “Popular Patristics Series” from St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, an Eastern Orthodox publisher, the volume contains seven Lenten kontakia, in both the original Greek and in an excellent English translation.

To show you how good he is, I want to focus on his kontakion on the Prodigal Son, which was written for the second Sunday of Lent, not Maundy Thursday, but a communion service nonetheless, making it a profound meditation for today.

The hymn tells the familiar parable, but it does so in a way that puts the worshipper or the reader in the place of the Prodigal Son! It begins with a prelude,

O Lord, I have emulated the prodigal son by my senseless deeds and, like him, I fall down before you and I seek forgiveness. Therefore, do not despise me, Master and Lord of the Ages.

Romanos tells the story backwards, beginning with the father preparing a feast for his wretched son. Superimposed on the father of the parable is our Heavenly Father:

“I saw him and I cannot allow myself to overlook his nakedness; I cannot bear to see my divine image like this. For the disgrace of my child is my shame;

I will consider the glory of my child my own glory. Hurry then, my servants and ministers, to make all his limbs beautiful once again, for they are objects of my love.”

The details from the Scriptural account become symbols of salvation, as the robe with which the father clothes his son becomes also our being clothed with Christ’s righteousness, and the ring he gives him becomes the seal of salvation, and the shoes he puts on his feet become the means by which he can trample Satan, and killing the fattened calf for him recalls the sacrifice of Christ.

And at the climax of the poem, the feast that the father has prepared for his prodigal son morphs into the Lord’s Supper, which we worshippers are about to receive when the hymn is over and the service starts up again.

The effect, which we modern readers will also feel, is to make us realize that we are prodigal sons, and that our Father in Heaven has forgiven us, and that He welcomes us to the great banquet that is Holy Communion!

Romanos also continues the story of the elder brother who, in the parable, resents how his father gave his rebellious son such a feast. We hear the dialogue between them. But in the telling of Romanos, the father convinces him to welcome his repentant brother and to join the feast.

This goes beyond the text, of course, as Jesus ends His parable by leaving the question of the elder brother hanging. But the resolution by Romanos is at least plausible, since the elder son has never disobeyed his father, who now tells him to accept his brother and join the celebration. Either this son stays obedient or storms out to become another prodigal son, the story applies to him as well.

Romanos does this to write about two kinds of believers, those who have been Christians for all of their lives, and those who have converted after a life of sin. Both are recipients of salvation.

Ineffable, inexpressible is your compassion for those who are saved, O Lover of humankind, for you always heal the righteous, while you call sinners back again.

The righteous you kept safe, while the other you saved, you the Master and Lord of the ages.

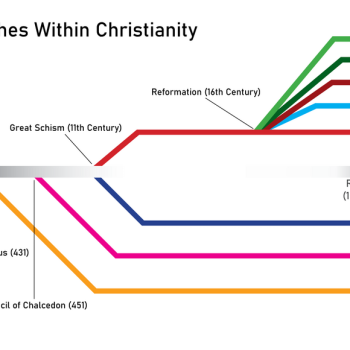

St. Romanos wrote before the Great Schism that divided Eastern and Western Christianity. Although there are elements in his writing–such as his devotion to Mary–that we evangelicals and Lutherans would not go along with, he expresses the Christ-centeredness of the Early Church that we can appreciate. (He even has a great distinction between Law and Gospel in his kontakion about Jonah, describing the gourd tree that God gives to the indignant prophet who sits in its shade as the Law, which is then withered by the far-greater sun of the Gospel.)

He deserves to be better known among English-speaking Christians. And maybe someday we can add some of his kontakia to our repertoire of hymns.

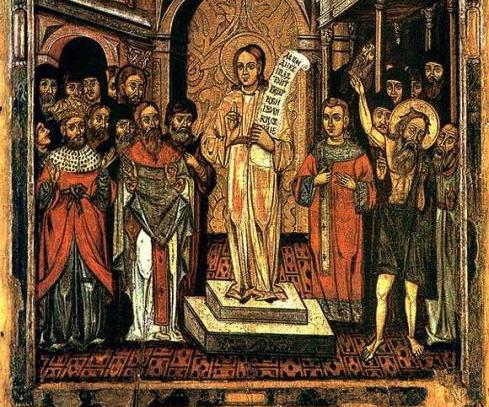

Illustration: Icon of St. Romanos the Melodist (1649), detail, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons