We’ve blogged about how editors are re-writing the works of Roald Dahl, R. L. Stine, and Ian Fleming to make them conform to contemporary woke sensibilities.

The Guardian in the UK has responded to the furor with an article saying that the use of “sensitivity readers” to flag problematic content is nothing new, that publishers often employ them before publication and that some authors themselves hire them before they submit a manuscript, just to avoid printing anything unintentionally offensive.

It’s time for a tutorial. For all of my writing about religious topics, my primary economic vocation before I retired was literary historian. Related to that discipline is textual editing. If you pick up a novel by a classic author, you might find the words “critical edition,” or “edited by” someone you’ve never heard of. Please bear with me while I explain what that means.

The basic process, then and now–except for the new possibility of electronic self-publishing–is that an author turns in a manuscript to a publisher, who edits it, sets it into type, prints it, and distributes the book to be sold. In previous centuries, publishers and editors often felt free to change the manuscript as they pleased. Usually this was just matters of spelling, grammar, and punctuation, but sometimes they changed the wording.

In addition, especially when the book would go through new printings, the author would also often submit changes and revisions.

This means that the text of the novel that we read is not necessarily exactly the way the author originally wrote it.

What a textual editor does is restore the book according to the author’s intentions. This means finding the original manuscript, when possible. Sometimes, though, there are different manuscripts, all by the author, with false starts, different ideas, revisions, and cross-outs, as the writer was working out ideas for the work. Textual editors then have to sort out the process of the author’s writing and attempt to put together the different fragments.

If there are no manuscripts, textual editors work from the earliest edition that had the author’s approval, usually the first edition. The manuscript, reconstructed manuscript, or the first edition becomes the “copy text.”

Textual editors then track the publishing history of the text, tracking the various changes that were made. Then, using various biographical sources such as correspondence, the editors sort out which changes were made by the author, as opposed to those made by the publisher.

The “authorized” changes–that is, those made by the author–are made to the copy text. Other changes are dropped, though textual editors will often keep corrections of spelling and punctuation, often with a footnote to indicate the author’s original version. Other footnotes may give the author’s original version, plus the various revisions made by the author, which demonstrate the writer’s ongoing thinking about the work.

All of this will result in the publication of a “critical edition” of the author’s work. The criterion, always, is to recover the author’s intention. The purpose is to give readers the author’s style, meaning, and aesthetic form, since the author is generally a better artist than the publishers.

During the 19th century, classic texts were often “bowdlerized,” a term that derives from the name of Thomas Bowdler, who published The Family Shakespeare, an edition of Shakespeare with all of the sexual references, innuendos, and profanity removed, so as to make the bard suitable for ladies and children to read, according to the standards of Victorian prudishness. Textual editors work to undo the bowdlerization of texts to restore what the authors originally intended to say, offensive or not.

Today, publishers are not prudish about sex or profanity, but they are prudish about race, gender, and social justice issues, according to the standards of woke progressivism. So bowdlerizing texts has come back into fashion. And the author’s intentions are erased.

To return to the Guardian article, when an editor uses a “sensitivity reader” before publication, this is no different than other kinds of editorial feedback a writer will receive. Good writers appreciate good editing. When an editor catches a mistake or makes a grammatical correction, most writers are grateful. The practice today is for writers to see the edited text and either approve it or, sometimes, argue with the editor until they come to a consensus. The edited text, when approved by the author, conforms to the author’s intentions.

If some authors go so far as to hire “sensitivity readers” themselves, not wanting to stray from any canons of political correctness, that is their privilege. Any revisions the author makes at the behest of the “sensitivity readers” and put into the manuscript sent to the publisher reflect the author’s intentions. That is fine.

What is problematic is bowdlerizing dead authors, who cannot agree to the changes, which, by definition, go against their intentions. The estates of the authors–often children or grandchildren of the writer–have an interest in selling more copies and thus in adapting them to contemporary tastes. The estates must approve and often even initiate “sensitivity” revisions. But their approval is not the same as authorial intention.

Worse, though, is revising a text and publishing it in a new edition without a living author’s knowledge, permission, or approval. This is what happened with children’s author R. L. Stine.

Respecting the author’s intention is an important principle not just for textual editing and for interpreting literature. It is also an important–though contested–principle for the interpretation of the Constitution, as well as other laws, and for interpreting the Bible.

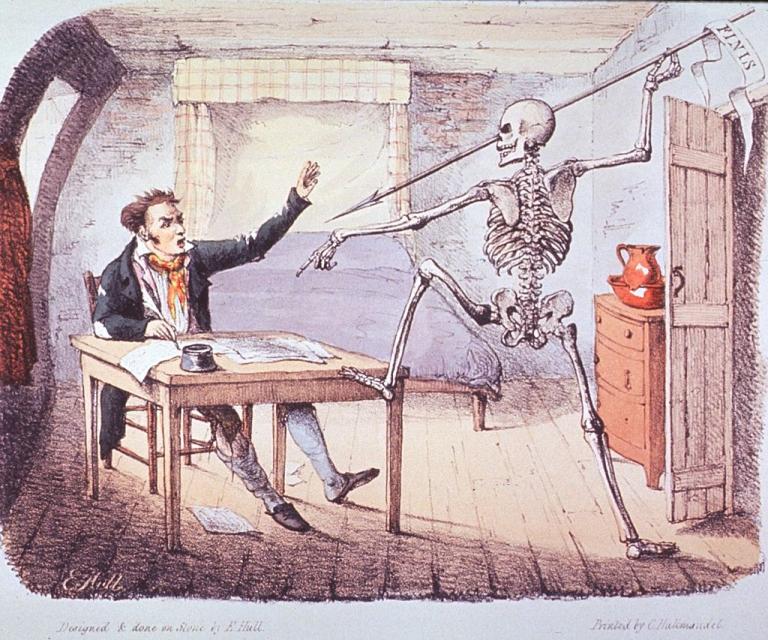

Illustration: “Death Found an Author Writing His Life,” by Edward Hull, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons