As I said in yesterday’s post, in scouring the internet searching for the source of a Luther quote on laughter, I came across several articles on Luther’s humor–his wit, his satires, and even his scatology, which one scholar found similar to that of another Renaissance monk and scholar, the comical but filthy genius Rabelais–and how this relates to his theology.

Luther is certainly the one major theologian who, in the midst of the most serious and intense reflection, will make you laugh. C. S. Lewis and G. K. Chesterton have that power also, but they are religious writers, not theologians, as such.

Carl Trueman, who is both a religious writer and a theologian of the Reformed variety, said this in the conclusion of his book Luther on the Christian Life: Cross and Freedom. As published in World as “Laughing with Luther“:

Over twenty years ago, I was being interviewed for what would prove to be my first tenured appointment at a university. Halfway through the ordeal, one of the interviewers asked me, “If you were trapped on a desert island, who would you want with you—Luther or Calvin?” My response was reasonably nuanced for a reply to an unexpected question: “Well, I think Calvin would provide the best theological and exegetical discussion, but he always strikes me as somewhat sour and colorless. Luther, however, may not have been as careful a theologian, but he was so obviously human and so clearly loved life. Thus, I’d have to choose Luther.” Later that day, I was offered the position of lecturer in medieval and Reformation theology.

After Trueman expresses his appreciation for the objectivity of Luther’s theology, he takes up Luther’s humor:

In general terms, of course, Protestant theologians have not been renowned for their wit, and Protestant theology has not been distinguished by its laughter. Yet Luther laughed all the time, whether poking fun at himself, at Katie, at his colleagues, or indeed at his countless and ever-increasing number of enemies. Humor was a large part of what helped to make him so human and accessible. And in a world where everyone always seems to be “hurt” by something someone has said or offended by this or that, Luther’s robust mockery of pretension and pomposity is a remarkable theological contribution in and of itself.

I think there is probably a theological reason for Luther’s laughter too. Humor often plays on the absurd, and Luther knew that this fallen world was not as it was designed to be and was thus absurd and futile in a most significant and powerful way.

Luther knew that the tragedy and the comedy of fallen humanity is that we have such a laughable view of ourselves: one that would aspire to tell God who and what he must be. As humans are at once both righteous and sinful, so human existence is at once both heartbreaking and hilarious.

Eric Gritsch wrote an entire book on the subject: The Wit of Martin Luther:, which he summarized in an article entitled Martin Luther’s Humor. It begins with this:

Martin Luther (1483–1546) is the only “church father” who incorporated humor into his life and work. He did so by posing as a court jester (an advertised self-image), a quick wit, a facetious wag, and a sit-down comedian with humorous comments in more than five thousand “table talks.” His humor has to be taken seriously as an integral part of his literary legacy in the still-incomplete Weimar Edition of more than a hundred oversized volumes, published since 1883. Though known for many proverbial witticisms (“No one can become an expert among ignoramuses”), Luther made humor an integral part of his extensive theological reflections.

The most interesting study to me, literary historian with a specialty in the Renaissance that I am, was The truth of laughter: Rereading Luther as a contemporary of Rabelais Dialogism in An International Journal of Bakhtin Studies, 1 (3), 52-77, by a scholar from the Netherlands named Hub Zwart.

François Rabelais (died 1553) was a French monk, Greek scholar, physician, and satirist, known best for his sprawling comical proto-novels Gargantua and Pantagruel. These books capture virtually all of the issues and the accomplishments of the Renaissance and are hilarious, but they are also notoriously rude and crude, turning bodily function jokes into an art form. Rabelais lampoons the corruption of his day, including that of the church. Though he was a monk, he speaks positively of “evangelical preachers,” the E-word referring then to Lutherans, one of the few groups that escape his pen relatively unscathed. Not that he was one, as far as I have found. He was probably closer to his fellow humanist scholar Erasmus.

Mikhail Bakhtin was an influential Russian thinker and literary theorist, one of whose books was Rabelais and His World. In it, he related Rabelais to the spirit of the medieval carnival (as in Mardi Gras), defined his style as “grotesque realism,” and looked at the social role of laughter, arguing that “laughing truth … degraded power.”

Zwart relates what Bakhtin says about Rabelais to Luther, who at least once refers to Gargantua and so probably read him. Zwart, drawing on Bakhtin, says that medieval scholasticism, like the church and the society as a whole, was hierarchical, formalistic, and abstract, with the effect of promoting “gothic terror” (think the continual worry about Hell and the threat of thousands of years in Purgatory even for the saved). The exuberance of Rabelais in society and Luther in religion countered that strict and claustrophobic system. Their earthiness and emphasis on the body in its “lowest” functions countered the abstract, disembodied nature of medieval thought, and the “gothic terror” was countered with the joyous freedom of laughter.

Zwart says that in the conventional reading of Luther “we are urged to distinguish between the theological content of his work – which is to be preserved and purified – and the vulgar remainder, the grobian elements that are abundantly present in his writings (and even highly characteristic of his style), but must be regarded as irrelevant or even inconvenient from a theological point of view.” But instead of trying to clean up Luther, Zwart tries to relate the two dimensions:

My re-reading of Luther, however, starts form the contention that it is impossible to detach ‘official’ content from the vulgarities and obscenities of his language, simply because there is a fundamental congeniality between the both. It was the basic mood of laughter that allowed him to discern a new and liberating truth in a setting that was still dominated by gothic terror.

Zwart says of Table Talk, “the laughing tone, the carefree vocabulary, the gross exaggerations, the fearless truth and the astonishing, uninhibited scholarship of Luther’s Tischreden are quite in accordance with the speech genre referred to by Bakhtin as “the Banquet form of speech, liberated from fear and piousness.”

He says of Luther’s conversion, “we are faced with a Gestalt-switch – a sudden transformation of a gloomy catholic into a jolly protestant, a sudden shift from gothic horror into Renaissance gaiety – due to the decisive experience of laughter.”

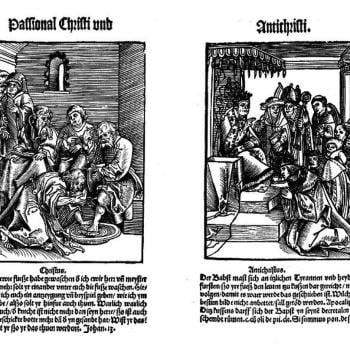

Recall that Luther was trying to reform an all-controlling church and an all-controlled society. Zwart says that Luther’s style–including his humor with all of its satire, coarseness, and insults–helped to achieve that. Here are some samplings of what he says:

Laughter is the sudden awareness of the lack, the shortcomings, the vulnerabilities of established discourse, of the official truth, otherwise held to be eternal and indisputable. . . .

Extra-temporal truths were exposed to ridicule, due to the techniques of laughter. As was explained above, one such technique consisted in degrading lofty discourse by reconnecting it with corporeal life, notably the body’s lower stratum. In Luther’s work, this technique is very important. It is quite prominent in his Prandial Conversations, but present in other, more ‘official’ works as well. Verbal abuse, relying on degradation, is a characteristic ingredient of his style. The persistent reference to bodily life is inherent to his carefree vocabulary, allowing 12 him to articulate his fearless truth. . . .

By verbal degradation, the terrible powers of the church became humanized, the intimidating vertical distance of the Word suddenly found itself reduced. Excremental abuses indicated that all human beings, whether Pope or peasant, are basically equal because the daily life of our bodies (notably their lower half) is basically equal. And this has a crucial topological effect. Due to carefree abuse, the frightening silhouettes of Pope, Cardinals and all the other once dreaded spokesmen of verticalized official truth are familiarized into human beings quite like us. . . .

Like in the case of Rabelais, Luther’s language and laughter destroy the “false idealization” of the established speech genres and render them implausible, in order for new forms of communication to become possible. The essence of his method consists in the destruction of habitual matrices – such as the identification of ecclesia with the Church of Rome, or the identification of Divine Justice with Divine Punishment – and the subsequent creation of unexpected associative matrices, including the most surprising logical links and linguistic connections – a freeing of consciousness that had become imprisoned within a tyrannical discourse.

This is a fascinating article, but I have some caveats, and not just because some of the quotations he gives includes language that violates the standards of appropriateness held by this blog. It has long been observed that much of what Luther writes cannot be printed in Lutheran publications. Which itself is extremely funny.

But Bakhtin’s Marxism is evident in his class warfare rhetoric and in his fondness for revolution. (Marxists consider Luther to be a social revolutionary, though using the language of religion, to overthrow the feudal order, which is a good thing, though the subsequent bourgeois order would later be overthrown by the proletariat.)

Zwart also exaggerates the difference between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. “Rabelaisian” humor, including satires on the corruption of the church as well as a measure of scatology, can also be found throughout medieval comedy, most notably in Chaucer. In fact, it was commonplace in comical and satirical literature through the 18th century, including with the clergymen Laurence Sterne and Jonathan Swift, up until the Victorian age. Perhaps cultures that didn’t have indoor plumbing were more frank about bodily functions and that we post-Victorians with our squeamishness and proprieties are the true outliers.

At any rate, Luther himself would sometimes confess that his vituperations were sometimes out of line and fell short of the love of neighbor and the love of enemies that Christ calls for. And it is never a good idea for those of us who are not comic geniuses like Luther and Rabelais to try to do what they did.

Illustration: Lucas Cranach, ‘Martin Luther as Augustinian monk’, 1520s, in: Cranach Digital Archive, https://lucascranach.org/en/PRIVATE_NONE-P201/ (Accessed 15.4.2023)