Jake Meador of Mere Orthodoxy has written an important post entitled The End of Evangelicalism and the Possibility of Reformed Catholicism.

He first heralds the demise of evangelicalism. He gives three reasons: (1) Its leadership failures, including the way evangelical leadership covered up sexual abuse and sometimes practiced it themselves; (2) the changed social climate, with modern evangelicalism taking shape when American politics was a rivalry between the center right and the center left, when marriage and family were the norms, and Americans shared a civil religion based on a Christian consensus, none of which is the case anymore; (3) its lack of a rigorous theology, due to its status as a centrist position between fundamentalism and the liberal mainline (both of which have transformed into something very different than they were) and its lack of confessional content.

In light of the end of evangelicalism, Meador proposes the building of a new religious movement, “a reimagined Reformed Catholicism, updated and modified to suit the missionary context facing us in the late 20th and early 21st century west.”

He acknowledges that this has been done before:

The original Reformed Catholics, of course, were a certain slice of early modern Protestants who saw themselves as reforming the church catholic, calling her to renounce the accumulated errors that had piled up in her theology over the centuries and which had been mostly ignored by the church’s hierarchy. Figures like Martin Bucer and Philip Melanchthon, along with their more famous peers like Luther and Calvin, did not see themselves as beginning ontologically new ecclesial movements.

Rather, they understood their work as being the continuation of the church catholic, stretched across time all the way back to Pentecost. This is, of course, why both Bucer and Melanchthon sought reunion with faithful German Catholics as late as the early 1540s at Regensburg and why they nearly succeeded in the task, were it not for the intransigence of both the Roman Cardinal Carafa and Luther himself.

Intransigence of Luther! The Diet of Regensburg, in which the Emperor sought to forge an agreement between the Papacy and the Reformation, was ill-fated because the distance between the sides was just too great. I’ll come back to the intransigence of Luther. I appreciate Meador’s diagnosis and proposal, but in minimizing Luther and ignoring Lutherans, he neglects the work they have already accomplished towards the goal he envisions.

Meador goes on to note both the similarities and the differences between the time of the early Reformation and today:

These early Protestants, rightly, recognized that the catholicity of the faith is found in its teaching, not in a singular church office. So they sought to preserve and pass on catholic doctrine for the church catholic amidst a time of political, cultural, and technological upheaval. Yet even so these men could presuppose Christendom. Their project was ultimately to conserve an actually existing Christendom by renewing it and calling it back to its first love.

The task before us is quite different. Ours is a post-Christian, perhaps even post post-Christian culture. Due to corruption and demographic collapse, we have very little left to conserve of the old American Christendom. Rather than conserving, it’s time to build. And it’s time to build a distinctly Reformed Catholic movement across the American church.

Meador describes what he has in mind, again with reference to the Reformation:

What does it look like theologically? It is “catholic,” which is to say it is historically rooted and it is universal. It does not seek to reinvent the wheel, but rather anchors itself in the historic thought of our fathers and mothers in the faith, as well as the great creeds and confessions that have defined what it means to be Christian. It is worth remembering, here, that the original vision of the first Protestants—a vision that many late medieval Catholics had varying degrees of agreement with!—was a moral and intellectual renewal of the one holy, catholic, and apostolic church. So it will be, must be, a conversation grounded not merely in specifically Protestant thinkers, though certainly in them, but in all the riches of the catholic faith—church fathers, medieval saints, and the witness of the Roman, Eastern, and Radical churches of the modern period.

We Lutherans certainly agree with that. But where are the Lutherans in his plans?

What does it look like ecclesially? Here we should work with the institutions we still have. In my experience, the PCA, OPC, EPC, ACNA, and ARP can all be fruitful vehicles for a historically grounded Reformed Protestant church life. . . .The PCA and ACNA have the largest role to play here, as they are the respective leading denominations in America for the dominant ecclesial traditions of the Reformed Catholic anglosphere. That said, the EPC is nearly as large as the ACNA while the OPC and ARP cumulatively represent around 50,000 church members, so each of these denominations can and should have a role to play in the broader diffusion of reformed catholicity. That said, because the PCA is the largest presbyterian communion and the ACNA is the largest Anglican, these two denominations will necessarily be central to the broader movement.

The initials refer to the Presbyterian Church in America (382,209 members), the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (32,255 members), the Evangelical Presbyterian Church (125,418 members), the Anglican Church in North America (122,450 members), and the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church (22,459 members). For a total of 684, 791 potential Reformed Catholics.

But the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod has, as of 2021, 1,807,408 members. The Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod has 340,511. The Evangelical Lutheran Synod has 19,394. So, not counting the plethora of smaller and independent churches, the total number of confessional Lutherans in the United States alone is 2, 167, 313. Which is more than three times the number of the confessional Calvinists whom Meador looks to as the the vanguard of Reformed Catholicism.

I realize that Lutherans, despite our large numbers, are not particularly influential in American Christendom. We tend to keep to ourselves, due largely to our fellowship concerns, but our theology is thoroughly worked out, and it is a matter of public record. Calvinists, though, are influential in American Christianity, despite their relatively small numbers. But some Christians with concerns similar to Meador’s are, in fact, discovering Lutheranism.

The basis of the debates at Regensburg was supposed to be the Augsburg Confession, the defining doctrinal statement of Lutheran theology that was written precisely to show the Reformation’s continuity with the historic church. But the Pope’s faction withdrew their earlier agreement to talk about that document, dooming the conference.

I would just like to make a friendly suggestion that Mr. Meador and his fellow Reformed Catholics study the Augsburg Confession and its Apology as a way of seeing what a Reformed Catholic theology could look like.

I realize that they probably couldn’t accept all of it, specifically, what it says about the sacraments. But any genuine attempt to bring together the best of both Protestantism and Catholicism will have to be sacramental.

In answering “what does [Reformed Catholicism] look like liturgically,” Meador says, “As much as possible, public worship of God’s people should be grounded in the great creeds and prayers of the faith, passed down to us through the ages.” He notes with approval the Anglican Church of North America, which has officially adopted the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, recognizing that some churches cannot be that liturgical, but that “it is still wise and good to sing old hymns and Psalms, to receive the Lord’s Supper regularly, to dedicate time each week to the public reading of Scripture and the preaching of the Word of God, and to adopt liturgical staples such as the call to worship, congregational prayer, and benediction and, in all these things, to hew closely to Scripture and historic practices and prayers.”

I appreciate his rejection of evangelical “contemporary worship,” but he should take a look at the historic Lutheran liturgy. Receiving the Lord’s Supper regularly is indeed a good practice, but a more robust understanding of what the Lord’s Supper is–namely, the true body and blood of Jesus Christ given for our sins–would be a good motivation for that frequent reception and would bring into these Protestant churches the “catholic” spirituality of the Early Church, the Middle Ages, and Eastern Orthodoxy.

Luther’s “intransigence” was directed not so much against the Catholic side of the equation as against the Protestant side, which would not accept Christ’s presence in the bread and wine of Holy Communion. I fear that this will prove to be a problem in this new movement also. But maybe not. I have known some Reformed folks who have drawn close to Luther’s understanding of Baptism and the Lord’s Supper.

I do recognize that “Reformed Catholicism” is a term originally used by some Anglicans, who managed to combine Calvinist soteriology with “Catholic” liturgy and a relatively high (though not by Lutheran standards) view of the sacraments.

Lutherans have been called “Evangelical Catholics,” reflecting the centrality of the Gospel (the evangel) in Lutheran theology, which we see expressed Baptism (being buried and raised with Christ) and the Lord’s Supper (in which He gives us His body and blood for the remission of our sins).

So I do see why Lutherans are not invited to the “Reformed Catholic” party. But I do think we could be fellow travelers and give those who are part of that movement some good ideas.

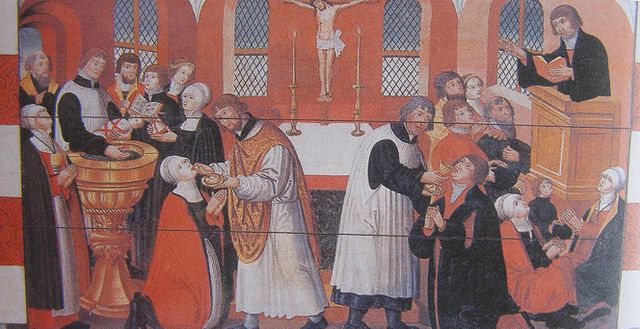

Illustration: Altar Cover showing Lutheran Worship in Denmark (1561) by Unknown author – Hungarian Codex, 2000, in the National Museum in Copenhagen, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6886328.