One of my Lenten disciplines, which I’ve practiced for years, is to read a book of heavy-duty theology. Sometimes this has amounted to a mortification of the flesh (sorry, St. Thomas Aquinas!). But the exercise this year has been an education, a stimulation, and a joy. I read Hermann Sasse’s This Is My Body: Luther’s Contention for the Real Presence in the Sacrament of the Altar. I could hardly put it down.

Hermann Sasse (1885-1976) is described in his Wikipedia entry as “one of the foremost confessional Lutheran theologians of the 20th century.” A theology professor at the University of Erlangen in Germany, Sasse vocally opposed Hitler, the Nazis, and the “German Christian” movement that sought to synthesize Nazi paganism with Christianity–to the point of wanting to remove the Old Testament from the Bible because it was “Jewish”–which took over the state church. Sasse became a leader in the “confessing church” and he authored with Dietrich Bonhoeffer the Bethel Confession, which, among various doctrinal affirmations, attacked the Nazi mistreatment of the Jews. (He did not, however, sign the later Barmen Declaration because it was being used as the basis for church union, despite the differences between the Lutheran and the Reformed confessions.) He broke completely with the state church and joined the the Free Lutherans, a small, independent, confessional church body connected with the “Old Lutherans.” The Wikipedia article says that he survived the Nazi regime because of his popularity with students and because he was protected by the Erlangen dean.

After the war, he accepted a call to teach at the Lutheran seminary in Adelaide, Australia. (The day after he accepted that call, he received another call from Concordia Seminary in St. Louis.)

Sasse wrote This Is My Body in English and it was published by Augsburg Publishing House in 1959. It focuses on Luther’s belief in the Real Presence of Christ in Holy Communion and his controversy with Zwingli. But its scope is much greater than that. Sasse explores what Christians have believed about the Sacrament from the time of the early church, through the Middle Ages, during the Reformation, and on into the modern world.

He notes that “No theologian of the Ancient Church ever doubted that, according to the words of institution, the consecrated bread is the body and the consecrated wine is the blood of Christ.” There was no consensus, though, in the early church about how that was to be explained. Ambrose taught that the bread and wine were changed into the body and blood of Christ, foreshadowing the later Roman Catholic teaching of transubstantiation. Augustine, while affirming the Real Presence, stressed that the sacraments were signs, foreshadowing the beliefs of Zwingli and later Protestants that the sacraments are merely symbols.

In the Middle Ages, according to Sasse, many views were put forth–including Berengar’s symbolic interpretation–until transubstantiation and the sacrificial view of the mass were made official dogma in 1215 and received their definitive explanation by Thomas Aquinas. Ironically, says Sasse, this would lead to a decline in sacramental piety during the late Middle Ages. Lay people and even monks and nuns would only receive Communion twice or four times a year, such were the fears of receiving it unworthily. Priests whispered the words of institution so they weren’t even audible to the congregation, which began to consider the elevation of the Host–whereby they could see Christ–became the high point of their worship. Because Aquinas taught that the bread becomes the whole Christ, the laity were not allowed to receive Christ’s blood in the wine, which was considered unnecessary.

Luther, though, in Sasse’s telling, revived sacramental piety. He affirmed the Real Presence of Christ on the basis of Scripture–“This is my body”–and rejected the attempts to explain this miracle by human reason. In this he was like the early church and also, says Sasse, the eastern church. Luther was actually willing to accept Christians who believed in transubstantiation–as he did not–as long as they believed in the Real Presence, or, to put it more strongly, that the bread is Christ’s body and the wine is Christ’s blood. And yet for Luther, Christ’s presence was not the only issue. Luther believed that the sacrament is the Gospel–Christ’s body broken for sinners; Christ’s blood poured out for the remission of our sins–and thus an instrument of God’s grace and His gift of salvation.

Other Reformers, though, would disagree, particularly the Swiss humanist Ulrich Zwingli, who with others stressed the chasm between the physical and the material, arguing that the sacraments signify Christ’s body and blood, that they are nothing more than symbols.

As the pope and the Emperor were gathering their military forces to exterminate the Reformation, many Protestant rulers–especially Philip of Hesse–were trying to organize a Protestant resistance. They felt that it was imperative for the various brands of Protestantism to come together. And the main issue dividing them was what to think of the Lord’s Supper. So Philip convened a “colloquy” at Marburg, in which the leading theologians and representatives of the various church bodies could thrash it out in the hopes of coming to an agreement. The two leading figures who would debate the issue would be Luther and Zwingli.

Here Sasse the writer is at his most brilliant. He includes a partial transcript of the Marburg Colloquy, reconstructed from notes taken by some of the participants and the observers! It reads like a play, consisting not only of dialogue but of vivid characters and intense conflict.

Both antagonists were strong debaters. Zwingli’s main argument is that, since His Ascension, Christ’s body is in Heaven. Therefore, it cannot be on the altars of churches on earth. Zwingli was working from the old three-story spatial worldview of hell below, earth in the middle, and heaven above. Luther contended that there are different kinds and modes of presence. God is omnipresent, so it is possible for Him to be present where something else is also present. That applies also to God the Son. Yes, retorted Zwingli, but God is a spirit. Christ’s spirit might be everywhere, but you are claiming that this is true of His body. Christ’s divine nature might be omnipresent, but His human nature cannot. Luther came back by insisting that since the Incarnation, Christ’s divine and human natures are united in His person. That sort of thing back and forth.

I wanted to yell out to Zwingli,”Ephesians 2:6! God “raised us up with him and seated us with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus”! If we are with the ascended Christ in the heavenly places and He can’t be on earth since He is in the heavenly places, then neither can we! That means you can’t be on earth either, Zwingli!

Luther had written “This is my body” with chalk on a table, covering it with a table cloth. When Zwingli would get off on arguments that “the bread signifies His body,” Luther would sweep off the table cloth and point to the words that Jesus said: “This is my body.” He didn’t say, “This signifies my body.”

Luther is usually depicted as the stubborn, intractable one, but Sasse says that Zwingli says that was a better description of Zwingli. Luther was the one who composed the Marburg Articles (quoted in full in the book), which said what areas they did agree on, such as justification by faith in Christ. These included an article on what they did agree on about the sacrament, clearing up the false accusations from both sides (e.g., the sacrament is not a work that we do; that there is a spiritual feeding on Christ by faith). It concludes, “And although at present we are not agreed as to whether the true body and blood are bodily present in the bread and wine, nevertheless each party should show Christian love to the other, as far as conscience can permit, and both should fervently pray Almighty God that He, by His Spirit, would confirm us in the right understanding. Amen.” So wrote Luther, who always said that while he could be harsh in his writing, he was usually gentle in person.

Zwingli agreed to the Marburg Articles but denied them later. And despite this incomplete agreement, they were sufficient to serve the political purpose of allowing the Protestants to form a united front against the pope and the Emperor.

What about Luther’s refusal to acknowledge Zwingli as a “brother” because “we have a different spirit”? Well, first of all, it wasn’t Zwingli he said that to, it was Martin Bucer. And Sasse cites Bucer’s claim that Luther told him that his withholding fellowship was due to Melanchthon, who wanted not so much a unity of Protestants but who held out hope for a unity with Rome.

Sasse goes on to discuss the understanding of the Lord’s Supper after Marburg. John Calvin, developing an idea from Bucer, worked to develop a middle ground, arguing that while the elements remain only bread and wine there is a real spiritual presence, in which we on earth feast by faith on the body of the ascended Christ which is in heaven. Sasse explains why that solution wouldn’t suffice for Lutherans. A key test case is whether unbelievers receive Christ’s body and blood if they partake of the sacrament. Calvin said no, since they don’t have faith. But the Word of God says, “Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty concerning the body and blood of the Lord. . . . For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment on himself” (1 Corinthians 11:27, 29). Again, for Luther, the issue was not understanding, not figuring out an explanation that satisfies human reason, but simply having faith in the Word of God.

Sasse traces the formulation of the doctrine of the Real Presence in the Formula of Concord and the status of the question in the centuries since. In the course of all of this, I learned some concepts that I had never thought of before but that greatly enrich my perception of the Lord’s Supper.

Some who argue against the Real Presence say that the body of Christ which we must discern (1 Corinthians 11:27) is the church. St. Paul in these passages, they say, is referring to the problem in the church at Corinth of turning the Lord’s Supper into a meal with feasting, drunkenness, status seeking, and humiliating the poor, thus despising the church of God (1 Corinthians 11:17-22).

Sasse discusses one of these passages, 1 Corinthians 10:16-17, in depth: “The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a participation in the blood of Christ? The bread that we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ? Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread.” The word translated “participation” is koinonia, meaning communion or community. Sasse shows that this passage has to refer to “the cup” as a communion in the blood of Christ, and “the bread that we break” is a communion with Christ’s body. This clearly speaks to Christ’s presence in the supper. But Sasse acknowledges the importance to this passage of the church and the communion that Christians are to have with each other. Then he brings those senses together: “Because the bread is the body, we who partake of this body are the ‘body of Christ.'”

Sasse also discusses the Apostle’s Creed, with its confession that “I believe in. . .the communion of the saints.” I have heard some Christians say, naively I thought, that this refers to believing in “communion.” Clearly, I had assumed, it refers to the church and the unity that all Christians have with each other. Sasse says that the Latin is ambiguous, so that it could refer to communion with holy people, or with holy things. In Greek, we have koinonia again. Sasse points out that the Apostle’s Creed, unlike the Nicene Creed, doesn’t repeat itself, referring to something different with each article. We have just said, “I believe in the holy Christian church,” before adding, “the communion of the saints.” Sasse cites the Orthodox liturgy, which brings those two senses together: “the holy things for the holy people.” Again, Sasse sees the communion of Christians with each other in one Body as being connected with our common participation in the Body of Christ in the Sacrament.

Sasse also discusses the eschatological dimension of the Lord’s Supper. It is indeed a “remembrance” that also looks forward to the End Times, “when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom” (Matthew 26:29). He comments that the church through the ages has looked for His coming again in glory. But His coming in the Sacrament is a foretaste of that great event, which culminates in the Wedding Feast of the Lamb. In the meantime, “it is this sacrament that made it possible for the Church to survive what in the eyes of the world must have been the greatest disappointment, the delay of his parousia.” Because He does come, in His supper!

One of the oldest of the church’s prayers that has been preserved for us, both in Scripture (as in the last words of Revelation and of the Bible) and in the most ancient eucharistic liturgies is “Come, Lord Jesus!” That petition, says Sasse, “is already fulfilled in His Real Presence in the sacrament.” I would add that this layer of meaning is also what makes the “common table prayer” so Lutheran!

But even in the Lutheran tradition, as Sasse shows, some have wandered away from this teaching and practice, especially in the modern world. “The decay of the sacrament in the modern world was bound to end in the decay of the Church,” he concludes. “And any rediscovery of the Church will begin with a rediscovery of the Sacrament of the Altar.”

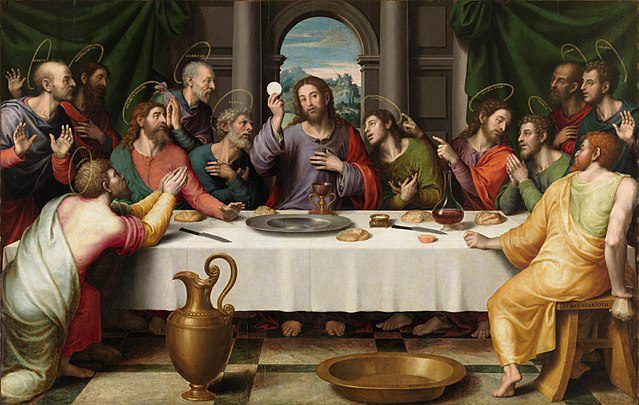

Illustration: Last Supper (1562) by Juan de Juanes – [2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23065137