When we hear of attacks on religious freedom, we usually think of government restrictions or overt persecution. But another kind of attack on religious freedom is emerging in the academic world from legal scholars who are arguing against the very concept of religion being a basic human right.

Notre Dame professor Daniel Philpott discusses this line of scholarship and answers it in his article for Public Discourse entitled Religious Freedom Deserves a Right of Its Own. One critique comes from the “liberal” tradition, which values human rights but simply believes that religion is not special enough to claim a right of its own:

Leading scholars of jurisprudence now argue that religion does not merit “special constitutional status,” in the words of Christopher Eisgruber and Lawrence Sager, and that “we [should] consider . . . abandoning the idea of a special right to religious freedom,” as Ronald Dworkin recommends. These three scholars doubt religion’s distinctiveness and maintain that it is arbitrary and unfair to privilege religion with a right that other forms of belief do not enjoy. They do not deny the value of religion, but they argue that it can be protected as simply one instance of a right to speech, conscience, or assembly.

Other scholars critique religious liberty from the perspective of postmodernism, arguing that religious rights are not universal but are an imposition of Western power.

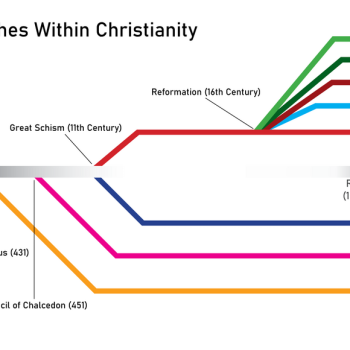

If these liberal critics question the distinctiveness of religious freedom, a second contemporary school questions its universality. They are postmodern thinkers, following in the tradition of Friedrich Nietzsche and Michel Foucault, who think that religious freedom is a product of social power in a particular time and place. The paterfamilias of this school is anthropologist Talal Asad, whose followers include Winnifred Fallers Sullivan, Saba Mahmood, Elizabeth Shakman Hurd, and Peter Danchin. Religious freedom, argues Asad, accompanies a conception of religion as inner belief, detached from everyday practice, that arose through the Protestant Reformation and the Enlightenment. Imperial states—including the United States today—then foisted religious freedom on peoples for whom the principle is a foreign import.

Both the liberals and the postmodernists, Philpott writes, have common assumptions about religion:

Behind both schools’ objections to religious freedom lies a common conception of religion: that it is a set of beliefs, commitments, worldviews, identities, and cognitive statements—all forms of propositions or affirmations that people hold in their minds. So the liberals ask why religious beliefs, rather than philosophical, ideological, or other spiritual beliefs, merit a right of their own, and postmoderns ask why such a modern and western phenomenon is promoted as a global human right. If religions mainly comprise beliefs, these objections are formidable.

Philpott then defends the right to religious freedom with an argument based on natural law. Religion, he says, is good in itself. That is, it is a “good” that is not just instrumental, leading to other good things. Rather, it is an end in itself, and is therefore intrinsically good. Human beings have a universal right to pursue what is intrinsically good. This is because whatever is an end in itself is a necessary facet of human nature. And that includes religion.

Similarly, “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” are good in themselves, and these and other intrinsic goods are protected in the Bill of Rights, which gives the freedom of religion the preeminent position.

I recommend Philpott’s essay not just for what it says but as a good example of reasoning according to “natural law,” which is NOT about what animals do, nor is it an application of principles drawn from scientific laws, nor is it a kind of environmentalism. Rather, it is a consideration of purposes and rationality, built on the assumption that human beings, society, governments, and reality itself have a “nature,” an inherent objective order according to which we should live. This concept of “natural law” goes back to Aristotle, but Christians also adopted it as a testimony to God’s creation and to its ordering according to the Logos, the mind, the design, and the Word who is the Son of God (John 1).

But you don’t have to be a Christian to recognize the natural law in this sense. Such arguments are in the realm of reason. A full account of human nature and the natural order requires the addition of God’s revelation, as given in His Word. But natural law has always been useful for Christians trying to make their case in the secular arena.

Of course, postmodernists do not believe in “human nature,” “inherent objective order,” “purpose,” “an intrinsic good” or “rationality.” So we can expect critiques not only of religious freedom but also of all other civil liberties.

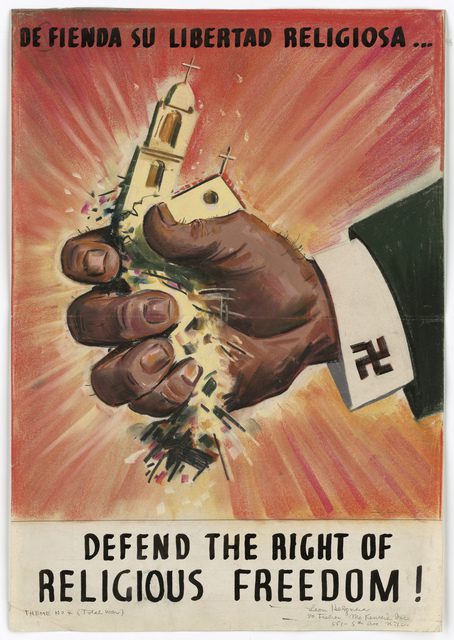

Illustration: World War II poster via Picryl, public domain