Many observers have noticed that when religion declines, other things–most noticably politics–rush in to fill the void. For example, woke progressivism has been shown to bear the marks of religion, from its view of sin, to the experience of conversion, to its exaltation of saviors.

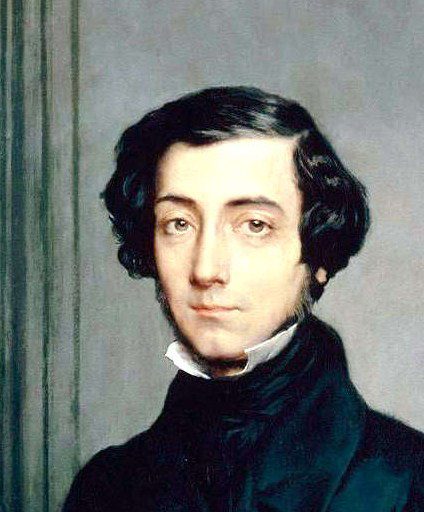

Georgetown political theory professor Joshua Mitchell goes deeper in his First Things article The Age of Incomplete Religions, which draws on a much older source. The 19th century French thinker Alexis de Tocqueville was a keen observer of early American society whose insights are still startlingly applicable. De Tocqueville also wrote about the French Revolution, which he witnessed at first hand.

He showed that while the most radical revolutionaries sought to wipe out Christianity, their fanaticism and their ideological convictions amounted to a new religion. But it was an “incomplete” religion.

Mitchell explains, after first defining the sense of “debt”–what we owe–in religion:

To begin to understand the place of this deeper, third kind of debt and economy, which we must grasp if we are to understand the sort of debt that identity politics has in mind, consider Tocqueville’s thinking about religion and its deformation. In 1835, in Democracy in America, he had written the following: “Eighteenth century thinkers believed that religion would die out as enlightenment and freedom spread. It is tiresome that the facts do not fit the theory.” The age of enlightenment would not blot out Christianity. In 1851, in The Old Regime, he added a new twist to his theory: The French Revolution, he wrote, was an “incomplete religion.” Christianity would weaken, and into its place would step one incomplete religion after another. After Christendom would not come “secularism,” but rather the age of incomplete religions.

Christianity is a “complete” religion. It is universal in scope and in resolution. All human beings because of sin have a “debt” they cannot pay. But God, through Christ, pays that debt for them. In an “incomplete” religion, God is left out, so that debts and satisfactions, sin and atonement, play out in relationships between human beings. As Mitchell explains it,

In Christianity, man is universally stained and, through a vertical irruption into history, he is saved from his stain and transgression. But in an incomplete religion, the vertical relation between man and God is reconceived as a horizontal relation between pure, mortal, innocent victim groups and impure, mortal transgressor groups. God does not “save” the world, man does, by expunging the impure groups (and the filthy things they have done, like invent capitalism and fuel industry with “dirty” petro-chemicals), so that the body-social may be cleansed. The impure groups have a debt they cannot repay, and so must be eliminated from the body-social.

Impure groups are demonized. Conversely, the pure groups are exalted as being above reproach:

The innocent victim is justified (to use not irrelevant theological terms), so that his revolutionary acts—say, guillotining landed aristocrats and churchmen during The Terror; slaughtering whole classes of citizens during the blood sacrifice that was communism; butchering Israelis on October 7; rioting, burning neighborhoods, and destroying livelihoods during the “mostly peaceful protests” in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death; or cheering on a would-be presidential assassin—are “covered over,” to use Christian language to explain the “pass” given to the parishioners of the incomplete religions that have befallen us since 1789. The legal status of what the incomplete religionists do may be criminal, but the legal debt they might owe is discounted or canceled because their act is justified in the third, higher, trans-legal economy of debt within which incomplete religions operate.

Mitchell then applies his points to the various “incomplete religions” that we have had to contend with:

Whether we are considering the French Revolution, communism, the ghastly simplifications of “post-colonial studies,” or the raging fire of identity politics in America and Western Europe today, the so-called innocent victim is never guilty, no matter how many laws he or she breaks. The stained transgressors, on the other hand, are forever under indictment, and need to vindicate themselves—hence the never-ending acts of performative justice we witness, say, by guilty white liberals, who several years ago painted “Black Lives Matter” on streets across America, did nothing to actually heal wounds and make the lives of the least among us any better, and quivered in the hope that social death would pass them over.

Can you think of other “incomplete religions” that take this form of a “pure” group seeking salvation by eliminating an “impure” group? The Nazis vs. the Jews, obviously, reminding us that Jews have long been a convenient scapegoat, including today. Radical Islamists act this way. And we have to confess that conservatives too sometimes fall into that syndrome.

As opposed to the “complete religion”: “For there is no distinction: for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a propitiation by his blood, to be received by faith” (Romans 3:22-25).

Illustration: Portrait of Alexis de Tocqueville (1850) by Theodore Chasserlau via GetArchive, Public domain